By Nicole Pechacek and Mikayla Roberts

WACO, Texas — In the early 20th century, the people of Waco dubbed their city the “Athens of Texas,” but so did Austin, Independence, Larissa, Marshall, Seguin, Sherman and Tyler at various times.

To buttress their claim as a center of arts, learning and commerce, the city could point to Baylor University, a nationally recognized institution of higher learning, and the Washington Avenue Bridge in 1902, the longest single-span steel bridge in Texas.

They could brag about the Texas Cotton Palace, an annual celebration and exhibition hall built to reflect the city’s position as the region’s top cotton producer, the city’s numerous churches and Dr Pepper, the nationally distributed soft drink invented at Morrison’s Old Corner Drug Store.

Waco, however, had another side.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

There were more saloons in Waco than there were churches, according to historians. City leaders created a massive legal prostitution zone called “The Reservation.”

And just three years after the city built the famous Washington Avenue Bridge, hundreds of residents gathered on it to watch a Black man hang from its girders.

That was the other Waco, a town where hundreds of people — as many as 15,000 white men, women and children, elected officials and law enforcement — gathered periodically to participate in massive public lynchings of Black men.

Twenty-two Black men were lynched in Waco and surrounding McLennan County between 1861 and 1922, according to data analyzed by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland. In the 1900s, eight lynchings occurred when the city was touting itself as a progressive oasis, according to data analyzed by the Howard Center.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

Lynching of Black men became part of a culture of public murder and mutilation accepted by residents and nurtured by the city’s most consistent leading voices, its newspapers.

Lynching in McLennan County was not always race-based, according to Jeffrey Littlejohn, project director of the Lynchings in Texas website and professor of history at Sam Houston State University. Lynching before and immediately after the Civil War could happen to anyone regardless of race for crimes such as stealing cattle or horses, he said, particularly in rural areas without law enforcement. Then, things changed.

“By the 1880s and ’90s, it becomes a racialized form of white supremacy,” Littlejohn said.

The rise of Jim Crow laws established a hierarchical system that protected white people from being lynched, according to Karlos K. Hill’s book, “Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory.” Lynching after Reconstruction was now something reserved for “inferior black bodies,” Hill wrote.

The victim of the first documented spectacle lynching in Waco was Sank Majors. Majors, whose age was given as 18 in the undertaking record, was a farmhand accused of raping the wife of Benjamin Robert, a white woman who was “about 17 to 18 years old”, according to The Waco Daily Times-Herald. The Texas State Historical Association records her name as Clintonia Beatrice Robert.

On July 12, 1905, under the headline “White Woman Victim of Criminal Assault,” The Daily Times-Herald reported that Robert had been at home while her husband was away when she noticed Majors walking through the yard.

According to Majors’ descendant, Nona Baker, 76, a retired teacher’s aide, the wife knew Majors because he worked for her family.

A July 12 article in The Daily Times-Herald reported that shortly after Robert noticed Majors’ path through her yard, she was attacked by an unknown Black man.

Baker, Majors’ great niece, said when Majors heard that Robert had accused him of the crime, he fled Waco with his older brother, Curtis Majors, who hid him in the bed of a wagon. Baker, who said she was told the story by her grandmother, Majors’ sister, said Curtis drove Sank to Marlin, Texas, to catch a train to Lockhart, Texas, a town his brother lived a few miles from. He was caught, however, and brought back to Waco.

On Aug. 3, 1905, The Daily Times-Herald story, “Majors Given Death Penalty By Jury,” reported “Mrs. Robert testified that during the struggle she saw a scar on the negro’s hand, though she could not see his face, and that she had since seen Majors and examined his hand, the scar being the same she had seen when she was attacked.”

Majors was found guilty after five minutes of jury deliberation, according to the news story. But on Aug. 6, 1905, The Daily Times-Herald reported Majors was granted a new trial on a “technicality of the law.”

“The evidence and the court trial was clear and conclusive, the finding of the jury was all right, but it is said just a little error crept in somewhere whereby a reversal of a higher court might be obtained,” the newspaper reported.

Majors, granted the new trial because of an error made in charging the jury, never received it, according to the Aug. 8, 1905 story, “Majors Was Hanged by a Mob.”

The Daily Times-Herald reported that while Majors was waiting in his jail cell, “The entrance into the jail was made by force, and an armed force of two-hundred determined men surrounded the jail.” The mob dragged Majors to the Washington Avenue Bridge where hundreds of people watched him be hanged, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

“As soon as this was over there was a rush for him,” the newspaper reported. “One or two persons ran up and pierced him with knives. One man secured a finger as a souvenir. His shirt was torn to shreds almost, and pieces were taken by the dozen as souvenirs. … Nearly every man took some souvenir with him. A rag from the body, a piece of rope, in fact anything that could be secured was taken.”

The newspaper did not name any of the people involved in Majors’ lynching. A Howard Center review of newspapers did not find stories that showed reporters asked law enforcement about punishment or an investigation into who was responsible for the crime.

After Majors’ death, The Daily Times-Herald reported a coordinated campaign to — through beatings and fines — silence African Americans who talked “a little too freely” about his murder.

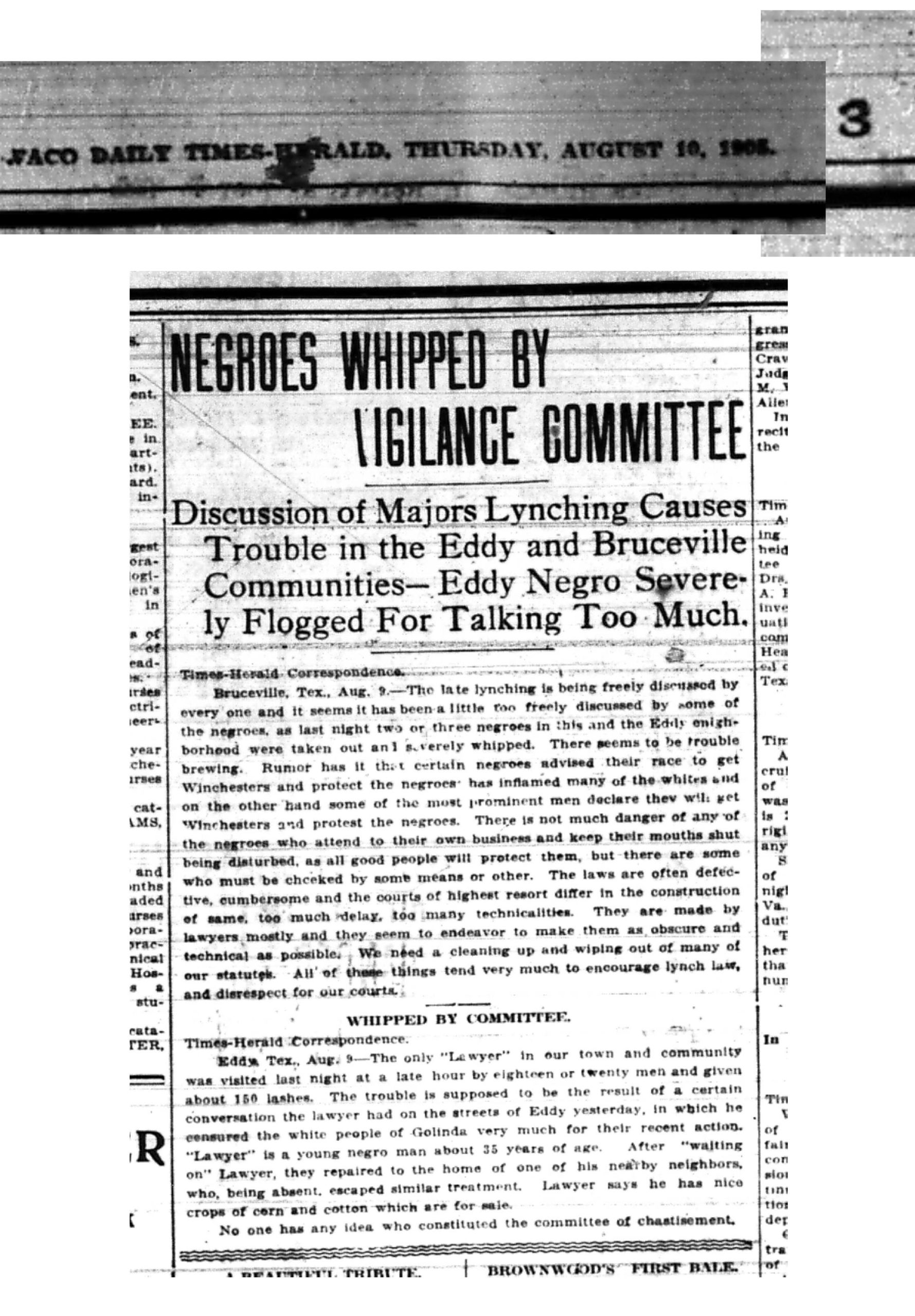

“Negroes Whipped by Vigilance Committee,” an Aug. 10 headline said. The publication reported “two or three negroes in this and the Eddy neighborhood were taken out and severely whipped,” the night after Majors’ death.

“There is not much danger of any of the negroes who attend to their own business and keep their mouths shut being disturbed, as all good people will protect them, but there are some who must be checked by some means or other,” The Daily Times-Herald wrote in the article.

The same day, under the heading, “Whipped By Committee,” the newspaper reported that a Black lawyer was “visited last night at a late hour by eighteen or twenty men and given about 150 lashes.” The lawyer received the lashes for “censuring” the white people of Golinda who participated in Majors’ lynching.

The Daily Times-Herald article said the men also went to the home of the lawyer’s neighbor “who, being absent, escaped similar treatment.” According to the story, “No one has any idea who constituted the committee of chastisement.”

None of the newspaper’s stories reported the names of the men who beat the Black men.

Under the headline, “Another Negro Fined Heavily By Judge Cammack,” the newspaper reported, “Judge Cammack fined Sam Footer, a negro, $100 for remarks concerning the recent lynching.”

The article states that Footer’s language was that of “severe denunciation” of the actions of the mob that hung Majors. Black people of “the respectable element” kept their opinions of the lynching to themselves or only shared them with other Black people but that “those desirous of causing friction with the whites have no hesitancy in giving vent to their feelings wherever they may happened to be,” the newspaper reported.

According to the article, “Police officers have been very prompt and ready to suppress those who seem determined to foment and create trouble, and this is the second instance wherein an offender has been given the maximum penalty.”

Nona Baker said she has continued to tell the story of Majors’ lynching, despite being told by relatives to stop.

“My mother and her siblings were brought up to not talk about Sank Majors,” Baker said. She said her relatives were terrified that “some descendants of that white woman that he was accused of might still be living” and retaliate against her.

Eleven years after Majors’ death, Jesse Washington, 17, a farmhand, was accused of raping and murdering Lucy Fryer, the wife of his employer, George Fryer.

On May 9, 1916, the Waco Morning News article, “Murder of Robinson Woman Breaks McLennan Records for Fiendish Brutality,” reported Fryer’s body was found the afternoon of May 8. The article named Jesse Washington as the suspect and reported his detainment. Officers also jailed Jesse’s younger brother, William Washington.

The article reported: “Within five minutes after [officers] had gotten to the scene of the tragedy, Deputies Lee Jenkins and Barney Goldberg of the sheriff’s department were speeding back to Waco with two negroes, one of them they were practically convinced from an unbroken net of circumstantial evidence, was the assailant.”

A May 10 story, “Tragedy on a Robinson Farm,” in The Waco Semi-Weekly Tribune reported Washington had confessed, been arrested and was taken to another county for safety.

A mob began looking for Washington immediately after his arrest, the Waco Morning News reported May 10.

Under the headline, “Farmers from Robinson Form Mob and Search Jail for Black Brute,” the newspaper reported: “Five-hundred determined but quiet men of the Robinson neighborhood came into Waco in autos last night with the avowed purpose of wreaking summary vengeance on Jesse Washington, a 22-year-old negro, who is the confessed slayer of Mrs. Lucy Fryar, aged 53,” misspelling Fryer’s last name.

Washington had been moved to Dallas before the mob arrived.

The May 17 edition of The Waco Semi-Weekly Tribune covered Washington’s trial. In the story, “Negro Burned to Stake in the Yard of the City Hall,” it was reported that “the court room was crowded before 9 a.m. No effort was made to keep any one out of the court room. … At 10 o’clock District Judge Munroe entered the court room and had to push his way through a mass of humanity to his bench.”

The Waco Morning News published, “Swift Vengance Wreaked On Negro After Jury Brings in Death Penalty,” on May 16 and reported, “The judge plainly asked the negro if he committed the crime, explaining to him that if he answered ‘guilty,’ it would mean hanging, life imprisonment, or not less than five years in the penitentiary. Washington’s plea of guilty was a muttered ‘Yeah.'”

Washington’s defense attorney asked one question and did not present a closing argument, the Waco Morning News reported. The jury reached a guilty verdict in four minutes.

Washington was immediately dragged from the courthouse by the mob through the back door, taken to the town square, where he was mutilated by knives and castrated, according to a May 17 article in The Waco Semi-Weekly Tribune.

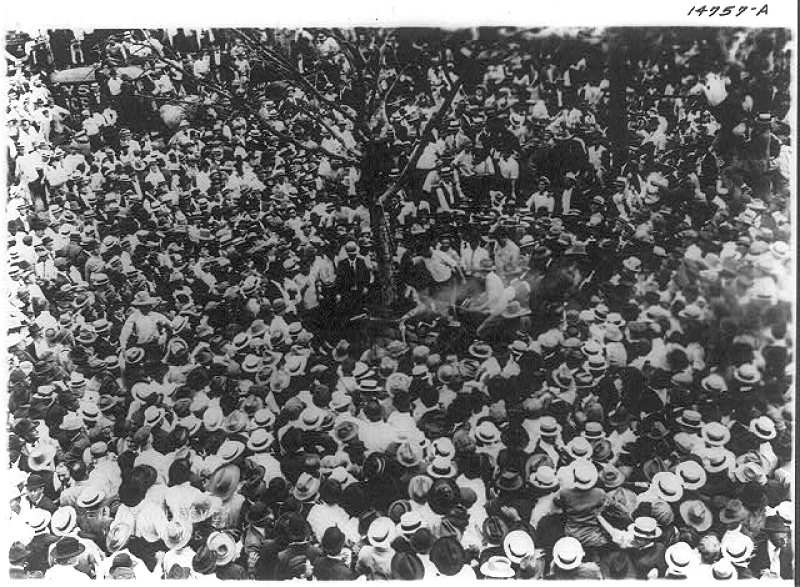

In the book, “The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP,” author Patricia Bernstein noted that as many as 15,000 people had now assembled, many of them alerted by word of mouth and the newspaper coverage, which reported the date and time of the trial. A pile of crates was set ablaze with a noose above it in the town center, where Washington was dipped into the flames until he was burned to death, papers said.

Participants took his bone fragments and part of the pyre as souvenirs. The Waco Morning News reported May 16 that “Bits of charred bone, links of the chain and even pieces of the tree were eagerly sought as gruesome souvenirs.”

According to the same story, “After the body had been burned to a crisp, a horseman came up, threw rope around the head of the corpse and dragged it through the streets of the city.”

Washington’s lynching and Waco became national news after photographs of the lynching were published alongside a story by the NAACP.

The NAACP’s magazine, “The Crisis,” said that “Photographer Gildersleeve made several pictures of the body as well as the large crowd which surrounded the scene as spectators. The photographer knew where the lynching was to take place, and had his camera and paraphernalia in the City Hall.”

“He was called by telephone at the proper moment. He writes us: ‘We have quit selling the mob photos, this step was taken because our ‘City dads’ objected on the grounds of ‘bad publicity,’ as we wanted to be boosters and not knockers, we agreed to stop all sale.”

Newspapers around the country, Black and white, condemned the lynching. The Chicago Defender, for example, ran a story “on Washington’s lynching and to announce the campaign to raise $10,000 for the Anti-Lynching Fund,” Bernstein wrote in her book.

Despite the intense criticism, another mass lynching happened in Waco six years later on May 26, 1922. Thousands of residents gathered for the lynching of the body of Jesse Thomas after he was shot for allegedly killing Harrell Bolton and assaulting Margaret Hays.

In the May 26, 1922, edition of The Waco News-Tribune, the article “Harrell Bolton Left Dead in Car; Negro Keeps Girl 3 Hours,” reported that Harrell Bolton and Margaret Harris were headed back to Waco when “a big black negro stepped out alongside” their car and fired a revolver at Bolton. Harris told The News-Tribune, “Harrell didn’t say a word – just dropped over in the seat with his head on the wheel. … I know he’s dead; the negro shot him at least four times, and then grabbed me in his arms and made into the woods with me.”

In her account with The News-Tribune, Harris told the newspaper, “He was a big negro and had a very prominent gold tooth.”

On May 27, the Waco News-Tribune article, “Mob Burns Negro After Father Of Girl Slays Black When Identified”, reported that Margaret’s father, Sam Harris, fatally shot Jesse Thomas after Margaret identified him as her assailant. While Thomas lay in a local funeral home, a mob of 6,000 white residents stole his corpse from the facility and, like Washington, burned his body in the town square, according to the story.

Police, however, believed Harris killed the wrong man, according to The News-Tribune. In a May 28 article, “Element of Doubt in Dead Negro’s Guilt Prevails,” police officers said they did not believe Thomas was responsible for the murder.

There is no available newspaper coverage stating Harris or the people who stole Thomas’ body and mutilated it were tried for their crimes.

Thomas was the last recorded lynching in McLennan County, according to data analyzed by the Howard Center. But the racial terror and violence became ingrained in the psyche of the county’s Black residents.

In 2006, the Waco Tribune-Herald became one of several newspapers, including the Montgomery Advertiser, Los Angeles Times, The News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, Orlando Sentinel and The Capital newspaper in Annapolis, Maryland, to apologize for its culpability in racial violence through its coverage.

“The editorial board of the Tribune-Herald wants to denounce what happened,” the newspaper wrote.

“We recognize that such violence is part of this city’s legacy. We are sorry any time the rule of passion rises above the rule of law. We regret the role that journalists of that era may have played in either inciting passions or failing to deplore mob violence.

“We are descendants of a journalism community that failed to urge calm or call on citizens to respect the legitimate justice system.”

Still, there is a veil of silence that hangs over the history of African Americans, residents said. Like Baker, they have been told not to repeat certain stories.

Baker said as recently as 2000, her family warned her repeatedly not to be interviewed by Bernstein for her book on lynchings in Waco. Additionally, African Americans were warned not to stray out of their strictly segregated community and some recall that as children, they were told to avoid places, like the Washington Avenue Bridge where Sank Majors was lynched, said Anthony J. Fulbright, a lifelong Waco resident.

Because of the culture of silence beaten into their ancestors after Majors’ murder, they were never told why.

Fulbright gathered recently in a local home with other Black residents to share similar experiences.

“I was told never to go across the Washington Avenue Bridge,” he said, “and I was given no reason; no explanation whatsoever.”