Yazoo City’s newspaper had a history of providing a forum for its pro-lynching readership

By Joelle Anselmo

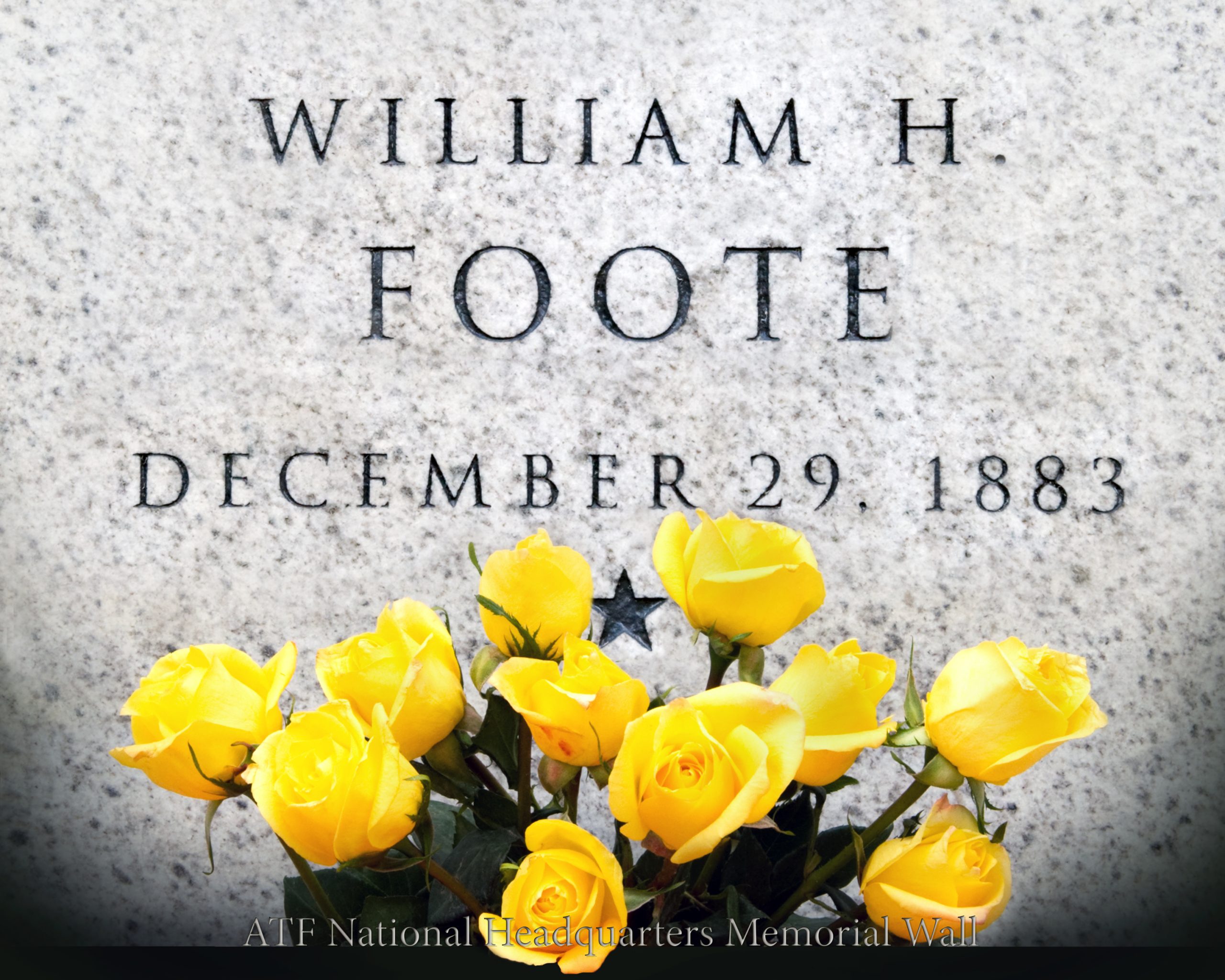

Bettye Gardner remembers her family telling her the tragic story of William Henderson Foote, her granduncle who was lynched in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1883. Foote’s death was one of at least 25 documented lynchings from 1875-1927 in rural Yazoo County, the Mississippi county with the most lynchings during the period, according to a Howard Center for Investigative Journalism analysis of the Beck-Tolnay Inventory of Southern Lynch Victims.

Foote, a Black federal deputy collector, was killed five days after a dispute on Christmas Eve, when he tried to save another Black Yazooan, John James, from being whipped, according to a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) report. The conflict resulted in four dead white men, according to some news accounts, and the arrest of Foote, along with 10 other Black people. An angry mob formed seeking revenge for the deaths, and lynched Foote, Robert Swayze, Richard Gibbs and Micajah Parker.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

Foote was born in 1843 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to a family that could trace its free lineage to his paternal grandmother. Because of this legacy, Gardner said Foote expected to be treated as an equal citizen. “He put himself in positions in Yazoo City, where, increasingly, whites were making threats against him and his family,” she said.

Foote was involved in politics and advocated for Black voting and civil rights. He was appointed the constable of Yazoo City in 1869, joined the Mississippi Legislature from 1870-71 and later became the town’s circuit clerk, according to the ATF. In 1880, Foote became a deputy collector in a town of 2,542 people, where he collected the revenue from liquor wholesalers and retailers.

On Dec. 29, 1883, he became the first Black federal officer killed in the line of duty, according to the ATF historian who researched the case.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

The Yazoo City Herald, a white-owned newspaper, covered Foote’s lynching and numerous other cases, sometimes delivering inconsistent or problematic reporting.

The Herald seesawed between justifying and opposing the act of lynching — in the case of Foote, doing so in the same story. It provided a forum to those with pro-lynching perspectives through letters to the editor. And it used dehumanizing language in reference to Black people.

It reported that Foote was shot and killed after he used an andiron to attack a man who entered his jail cell. An article described Foote as “a courageous man and a powerful one” and then compared him to an animal in the same sentence, writing “it is said he fought with the ferocity of a tiger and the courage of an African lion.” The mob hanged Swayze, Gibbs and Parker.

The same article about Foote presented the virtues of lynching and advocated against it, saying: “The lynching was a desperate remedy, but the disease was a desperate one,” and “whites frequently do the negroes great wrong, and should be punished more frequently than they are.”

In 1920, the paper mentioned Foote’s lynching in a piece called “A BIT HISTORICAL,” saying the Christmas riot of 1883 was a “dark page” of Yazoo’s history. The Herald wrote about the lynching again in 1976, providing a more complete, detailed version of the event and Foote’s role in the Yazoo community.

“Thus ended the last violence which was related to the tragic Reconstruction Era. W.H. Foote, from all indications a moderate during this struggle, was one of the last victims of its violence,” the article said.

In 2012, Barbara Osteika, then a historian for the ATF, was researching ATF federal officers killed in the line of duty for an honor wall the bureau was building. She discovered Foote’s story in reading an article Gardner had written for Southern Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the South, and newspaper articles.

“I became extremely interested in not only vetting but getting these stories out because these are federal law enforcement officers who make the ultimate sacrifice for a profession that sometimes doesn’t give back — especially, especially someone like Foote,” Osteika said.

The bureau recognized him at its headquarters in May 2012. Foote’s name was engraved at the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Judiciary Square in Washington, D.C.

“It was an amazing ceremony and just very well done and quite an honor that all those years later he would actually be honored,” Gardner said.

The Yazoo Herald reported on the ceremony in 2012, including an interview with Foote’s great-granddaughter, Patricia Nolcox. “It’s just been a wonderful legacy to come to life. … We had pictures, and we talked about it. But, it was just our story, the family story,” Nolcox said.

The newspaper’s ‘tremendous influence’

The Yazoo Herald, founded in 1871, now operates under the parent company Emmerich Newspapers Inc., and is run by publisher and editor Jamie Patterson. The paper was first established by James P. Clarke and has had 13 different owners.

In 1937, the Works Progress Administration reported on the Yazoo County press and its role in the community. “In the old carpet-bag days, the paper [The Yazoo Herald] supported the cause of white-supremacy, when it was hazardous to do so,” the report stated.

Former editor Jason Patterson said the newspaper played an influential role in the community.

“There’s no question in my mind that during the era, when you didn’t even have all of these other competing sources of information like you do today with various social media, 24-hour television and radio, and everything you can think of, when the newspaper really was your source of news, I feel like it probably had tremendous influence,” he said.

Historical editions of the newspaper contain multiple examples of taking a stance on lynchings or allowing its readership to do so.

In 1901, the paper published a letter to the editor with the headline, “LYNCHINGS AND MOB LAW; ‘Veritas’ Would Hang all Rapists, Without Priest, Minister or Jury,” saying it was in response to an earlier piece condemning all people who lynch and don’t let the law seek justice.

“Now, I am in favor of lynching the brute who commits rape every time and under all circumstances. If it be unlawful to hang by the citizens, then I am in favor of the law being so changed as to give every sheriff full authority to organize a posse of citizens and hang the brute without judge or jury or the administration of priest or minister,” the letter said.

In 1903, The Herald published “Extracts From the Sermon of a Chicago Minister:” under the headline “AN OBJECT LESSON TO MISSISSIPPIANS,” which argued for lynching while trying to separate it from the issue of race.

“We shudder at the torture of the criminal who is burned, but apparently forget to shudder for the innocent girl whose mental and spiritual agony is tenfold greater than that of the fire. This is not a race problem except so far as one race are the offenders. The white man who commits the same crime is just as guilty,” the extract stated.

The paper’s coverage of other lynching cases besides Foote’s also was inconsistent.

In 1899, Willis Boyd, C.C. Reed and Minor Wilson were lynched after a racial disturbance at Dr. R.V. Powers’ Refuge plantation in Sharkey County. The Yazoo City Herald said “Reed seems to be the leader of the negroes” and, “He is said to have been a sharp, shrewd negro” and had a “mean disposition.”

A week later, The Herald owned up to its sloppy reporting in the case, saying it had learned the evidence against the men was “very slight” and declared the lynching “horrible and inexcusable.”

Bryan Davis, current publisher of The Enterprise-Tocsin in Indianola, Mississippi, researched one of the state’s most famous lynchings. Luther Holbert and an unidentified woman, believed to have been his wife, were burned at the stake in 1904 in Sunflower County. The couple was chased over 100 miles through four counties, including Yazoo, with bloodhounds and a mob that grew to 1,000 people, some newspaper accounts said. During the manhunt, two Black men mistaken for Holbert were killed.

Davis was shocked when he first read about the case, especially how it was described in newspapers.

“It wasn’t like you were reading something horrific like it actually was. It was like you were reading a firsthand account from a press box at a baseball game,” he said.

The lynching received continuous national newspaper coverage, with some writing about the urgency and excitement of hunting down Holbert and the unidentified woman. Others vividly described the torture they endured.

Holbert had been accused of killing James Eastland, a prominent planter in nearby Sunflower County. Eastland’s brother, W.C. Eastland, was accused of murder for causing Hobart and the woman to be burned at the stake but was later acquitted. The Yazoo City Herald briefly covered the lynching but didn’t acknowledge the trial.

In 1905, The Herald also reported on the case of Talcum and Arthur Woodward, who were accused of assaulting a prominent white planter, Andrew White. The paper, after stating that one of the Woodwards drew his gun first, said, “Parties from Silver City say the negroes were not hung, but given a good beating and told to leave the country and never return.”

A week later, the newspaper printed that they were not lynched but were working in another part of the county “and will obey the warning given them.”

However, several other papers, including The Wichita Daily Eagle reported the Woodwards were lynched “by a mob of fifty persons.”

A change in ownership and coverage

The Yazoo Herald shifted under the ownership of the Mott family, which purchased it in 1914 and owned it for 64 years, according to articles describing the paper’s history.

Norman A. Mott III worked at the paper throughout his youth with his father, Norman A. Mott Jr., who ran the paper from 1955-77.

“My dad was much more even-handed and avoided a lot of the inflammatory things that other newspapers engaged in. He was not a firebrand segregationist nor was the paper a tool for that,” Mott said.

Jason Patterson credits the Motts with changing The Herald’s coverage, saying it wasn’t as much a conscious effort but more “people that were trying to do what they thought was right.”

Yazoo City is home to about 11,000 people, with 85.4% of the population being Black, 11.7% white and the rest divided among other ethnic groups, according to the 2019 Census. Although the county’s demographics have historically shown a majority Black population, Patterson said The Yazoo Herald’s current ethics and reporting are drastically different from its past.

“We do not let our personal feelings stand in the way of the truth, and sometimes that’s kind of tough in a small community paper where you encounter some of the same people that you write about,” Patterson said.

“I would obviously be appalled about anyone taking a stance for it [lynching]. … It’s impossible to justify that.”

He added, “I think that The Yazoo Herald’s record, for certainly as long as I’ve been here and before that, it speaks for itself.”

Ralph Eubanks, author, professor and Mississippi native, said the press was a factor in the racial terror. “The media, for the most part, kept that whole segregationist Mississippi way of life narrative. They helped perpetuate that, I would say, well into the ’70s after integration,” he said.

Grace Hale, a historian and writer on the South, said the Black press, including The Chicago Defender, was constantly trying to counter the stories the white press was printing.

“At that point, you see dueling narratives with whites always trying to prove that the person actually was guilty and Black activists always trying to say the person wasn’t guilty,” she said.

Hale said that in most of the rural South, small-town paper editors had complete control over what was published. “[T]hey just collude with police officers and sheriffs and court officials to not cover it,” she said. “So if it doesn’t get covered and nobody from that area calls up The Chicago Defender or one of the other Black newspapers and reports it, it just never gets into the news.”

Gardner said her mother told her the story of Foote because she thought it was important. She has met others who don’t know about their past, as it might have been too painful for their grandparents to talk about.

“I think, as a historian, it’s really a mistake,” she said. “I think that’s why some people, Black and white, don’t really have a sense of … [their] family and who they were and what they did, and all these kinds of things.”

She said this is especially important because of the country’s ongoing racial reckoning.

“I think that it is important that children know the history of this country,” she said, “and know it in a real sense, not some made-up story about it.”