By Vanessa Sanchez

Hickman, Ky. — Holding 2-year-old Ransey in her arms, Annie Walker begged the Night Riders for mercy.

“Disregarding her pleadings, the infuriated mob opened fire and a bullet pierced the body of the infant. A second shot struck the mother in the abdomen and she fell, still holding the dead body of her infant,” the Public Ledger newspaper reported.

Described as armed, masked and riding horses, a mob of about 50 people rode to the Walker farm near Hickman in Fulton County on Oct. 3, 1908, and set the house on fire because David Walker refused to leave “to be whipped.” As the family attempted to escape, the mob shot him, his wife and their five children, including the 2-year-old. The Walkers’ oldest son burned to death inside the cabin, several newspapers reported. Three children survived.

In Western Kentucky and Northern Tennessee, the Night Riders had formed two years earlier. Born from a group of tobacco planters and fishermen resisting industrial monopolies, some turned into anti-Black armed vigilantes, historians say.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

Violence escalated in 1908, when about 14 African Americans lost their lives at the hands of mobs. In addition to the Walker family, the cases included four men lynched in Russellville, Kentucky, and lynchings and terror that drove out the Black citizens of Birmingham, Kentucky, historians and researchers found.

As violence escalated, Kentucky newspapers contributed to a climate of terror by calling the victims bad negroes, “barbaric” or lazy and promiscuous. The (Louisville) Courier-Journal reported the “negro’s tendency to crime” on its front page, and small-town newspapers such as The Hickman Courier reprinted notes of warning: “To the Nigros of Hickman You are expected to Be absent May the 1st 1908 — espsly H—-s and Loffers or there will be Something doing. We Mean Bisness.”

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

‘In their place’

The Night Riders’ visit to David Walker, who owned a 2 ½-acre farm, was prompted by an altercation Walker had with a white woman. When they arrived, Walker defied the mob. “He tried to protect his family and stood for himself,” said Melinda Meador, a local historian and attorney. His defiance was met with the “cruelest terms imaginable,” she said.

National newspapers condemned and expressed shock at the brutality of the attack, Meador said. The Hickman Courier, established in 1859 by editor George Warren, justified it. “Walker was a bad negro,” the paper reported on Oct. 8, 1908.

“The posse who killed the negroes went to his home with no other intention than that of giving the negro a good, sound thrashing, but were compelled to do violence because he brought it on himself,” the newspaper reported, without citing a source.

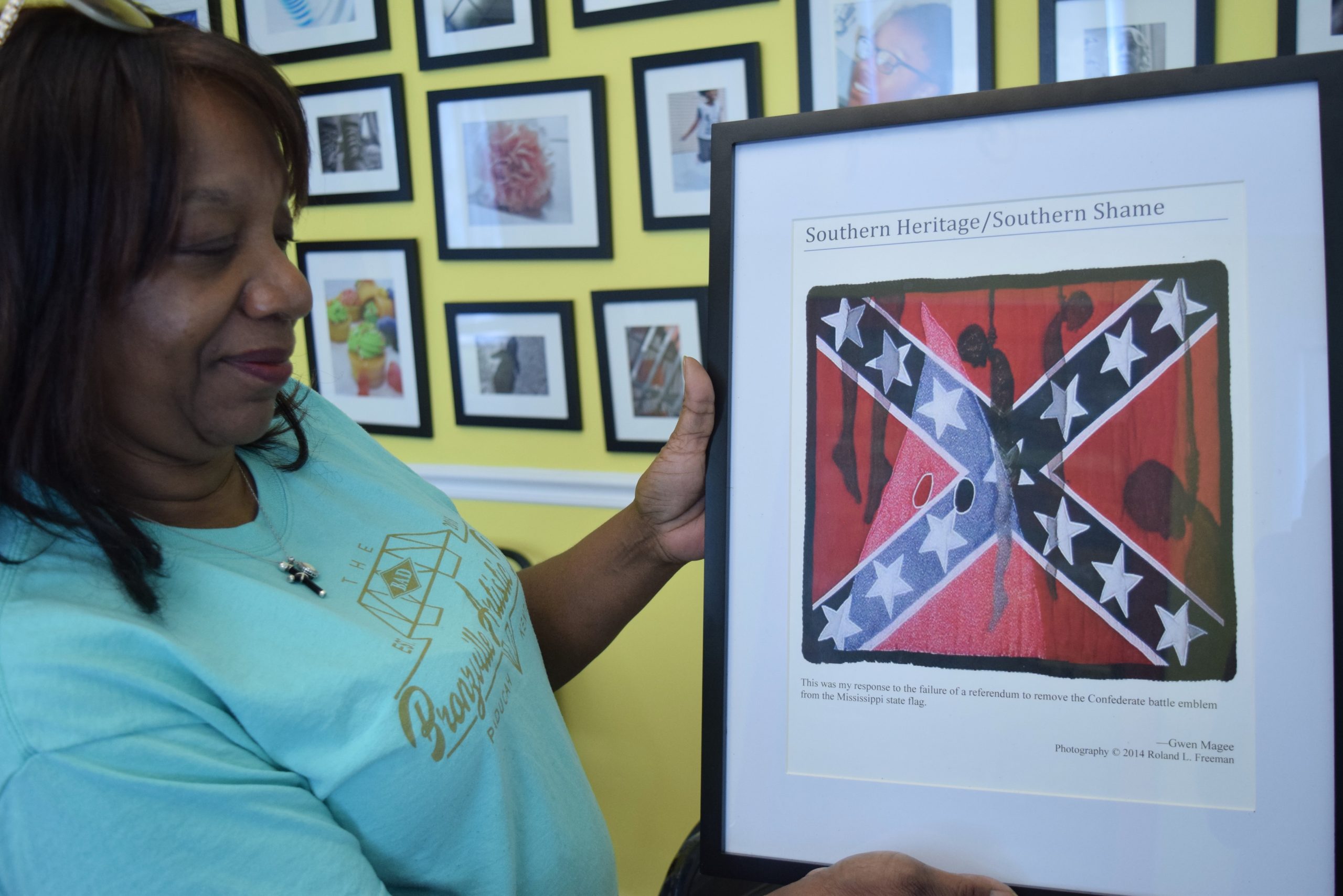

Photo by Vanessa Sanchez, University of Maryland.

“The characterization of lynchings in the newspaper was almost always defensive. There is always some rationale, there is always some reason for why someone deserved to be lynched,” Meador said.

Newspapers sometimes said it was too bad a lynching had occurred because it had brought shame to the community, said George C. Wright, historian and senior adviser to the president at the University of Kentucky. “But it would say it was justified because of the bad behavior of Blacks,” he said.

On Oct. 15, 1908, the newspaper printed a front-page editorial justifying the murder of the family. Walker “was no saint,” the editorial said, “neither his wife and 18-year-old girl, all of whom are said to have insulted a white lady with the most rank profanity.”

Anti-Black sentiment ran rampant in Southern newspapers, Wright said. “It’s almost hard to find Southern newspapers during that time, almost anywhere, that would have taken a different point of view,” he said.

In Jackson Purchase, a region comprised of eight counties in Western Kentucky, the pro-Confederate media appealed to white Kentuckians who felt betrayed because the government abolished slavery, said Berry Craig, professor of history at the West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah. “Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the Rebel press in Kentucky experienced a rebirth,” Craig wrote.

In 2017, The Hickman Courier, once a pro-Confederacy newspaper, merged with The Fulton Leader and The Hickman County Gazette and is now known as The Current, a newspaper based in Fulton, Kentucky.

Photo by Vanessa Sanchez, University of Maryland

Intimidate and scare

In Russellville, Kentucky, four nooses hang from the branches of a tree in a museum. Each noose represents a victim: John Boyer, Joe Riley, and brothers Virgil Jones and John Jones.

On Aug. 1, 1908, a mob of about 50 to 100 men dragged the four Black men out of the Logan County jail and hanged them on the same cedar tree where other Black people were lynched years earlier, The Courier-Journal newspaper reported.

The mob descended on the jail to kill and make them an example of the men, said Michael Morrow, archivist, curator and director of the Struggles for Emancipation and Equality (SEEK) Museum, where an exhibit is dedicated to the history of racial violence in Russellville.

Photo by Vanessa Sanchez, University of Maryland

Weeks before the attack, Rufus Browder, a Black man who was a tenant worker on a farm, told a jury he killed James Cunningham —‚ a white overseer at the farm and head of the Night Riders in Russellville — in-self defense.

The morning of July 13, Browder and Cunningham argued and “a shoot-out ensued; leaving Cunningham dead and Browder wounded,” according to a plaque at the SEEK Museum.

After Browder was arrested, a mob attempted to raid the jail. Logan County Jailer James Butts snuck Browder out of the prison and transferred him to Bowling Green to await his trial. Browder was sentenced to life in prison, where he died of tuberculosis, Morrow said.

Browder and three of the lynched men were members of the True Reformers lodge, a mutual aid society for Black people. The lodge had passed two resolutions after Browder’s arrest: one stating that Browder had acted in self-defense and another stating the lodge would raise money to help him pay for a lawyer, Morrow said. That didn’t sit well with some white people.

Joe Riley was not part of the lodge, but was lynched anyway. “He was at the wrong place, at the wrong time,” Morrow said.

The mob that lynched the men pinned a note to the body of Virgil Jones: “Let this be a warning to you n—–s to leave white people alone or you will go the same way. Your lodges and halls better shut up and quit.” The note can be seen in a postcard that circulated in the state.”

“Intimidate and scare,” Morrow said. “That is how you get people to not stand up for their rights, to not vote, to not protest.”

Newspapers wouldn’t call the mob Night Riders and a jury concluded the four men were lynched by unknown parties. Black families, however, believed Night Riders were involved in the lynching, wrote Suzanne Marshall in “Violence in the Black Patch of Kentucky and Tennessee.”

Morrow said he was 12 years old when he found a postcard of the lynching tucked within his grandmother’s friend’s Bible. When he was old enough, he started to find information on his own, he said. On the 100th anniversary of the lynching, Morrow fought to include the exhibit in the museum to “tell the truth” about what happened.

Primary sources, including court records and letters, helped him reconstruct the lynching. With newspapers he had to be extremely careful because of bias, he said. “Whites who owned these newspapers were not going to say ‘we are threatening these people bad,’” he said.

Logan County, where Russellville sits, had the second-most lynchings in the state: 17, according to Wright’s book “Racial Violence in Kentucky: 1865-1940. Lynchings, Mob Rule and ‘Legal Lynchings’.”

Some newspapers minimized the impact of lynchings. For example, The Hustler, a biweekly newspaper distributed in Hopkinsville until 1912, went beyond justifying the lynching of the four men in 1908. In an article in the Aug. 7, 1908, edition, the newspaper said “The lynching does not appear to have had any great moral effect on the negroes here.”

In the following days, newspapers spread rumors about what led to the lynching of the four men. “They told the people that the lynching was about Black people who were formed into a mafia-style mob to murder white people,” Morrow said.

Six days after the four men were lynched, The Hustler reported: “The negroes worked when they pleased and refused to work despite conditions whenever so inclined, and the farmers were compelled to submit.”

The Lexington Leader, which merged with the Lexington Herald in 1983 to form the Lexington Herald-Leader, said the “‘True Reformers’ were organized against the whites, that they meant to assassinate any employer who discharged a Negro and that the Cunningham murder was plotted.”

White-owned newspapers did not pursue facts when it came to understanding Black issues, Wright said. “The newspapers could be objective when it came to talking about many issues, but not race and the status of Blacks,” he said.

Under Morrow’s direction, with assistance from a community board and group of young people, the SEEK Museum is starting the conversation about racial violence in the town.

It hasn’t been easy. “When I put the exhibit up, people I’ve known all my life cussed me out,” he said. However, he said he believes these stories need to be told.

“Black people need to take that burden off and start understanding why they were so timid,” Morrow said. “It’s also important that you get these stories out because white America has cleansed so much to protect young white people from the truth.”

Land lost underwater

At the Hotel Metropolitan in Paducah, Kentucky, one of the last historical African American hotels in the country, Betty Dobson, director of the hotel museum and the Upper Town Heritage Foundation, said her former neighbor, Mama Erma Young, told her how she escaped from Birmingham in Marshall County, where the African American community was driven out by Night Riders in 1908.

Dobson said Young told her that her mother put her in a boat, trying to get the family to Paducah.

On March 9, 1908, a mob of about 150 Night Riders descended on Birmingham. After cutting the phone lines at midnight, the mob attacked Black homes and shot everyone who resisted, wrote investigative reporter Elliot G. Jaspin in “Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America”. “One hundred men rode into Birmingham last midnight and shot seven and whipped five blacks beside warning all the other negroes to leave under penalty of death”, The Courier-Journal reported the next day.

Two of the victims were farmer John Scruggs and his 2-year-old grandson, who were shot and later died. Some newspapers reported a baby girl was the victim.

“The Scruggs family is said to have borne a bad reputation and it seems that this means was adopted of rebuking them,” The Daily News-Democrat of Paducah wrote the next day.

On March 11, 1908, the newspaper printed an article stating that Scruggs was an innocent victim and some of his grandchildren were the real target. “The leaders of the band told him that they did not want to hurt him, but were after some of his grandchildren, who lived at the house and were regarded as nuisances in the community,” the newspaper reported.

The attack came after a sustained campaign to expel African Americans from the area, wrote Warden Hale, a detective who investigated the case, in an editorial published in The Courier-Journal.

“It was freely stated at the time of the Birmingham raid and several other similar attacks upon negroes that white men anxious to get an opportunity to buy the property of negroes at low prices promoted the raids to drive negroes out of the State,” The Courier-Journal reported four months later.

Almost every Black person left the town after the attack. The population plummeted from 348 in 1900 to less than 135, Jaspin wrote in his book. In 1950, only one African American could be found in Marshall County. By 1960, he was gone, according to Jaspin.

The town was flooded in 1937 to create Kentucky Lake. Marshall County has the reputation of being a “sundown,” county where Black people are not safe. Nearly 98% of people living there are white, according to U.S. Census data. Local officials approved raising a Confederate flag outside the courthouse in 2020, and KKK recruitment flyers were found in home yards in 2021.

On July 9, 1953, The Paducah Sun-Democrat — today named The Paducah Sun — printed an editorial commemorating Birmingham and the community that was relocated after the creation of the lake. “The town vanished, but not even time can drown the spirit of townspeople united,” wrote Sun Democrat city editor Bill Powell.

The editorial did not make any reference to the 1908 raid that led to the complete disappearance of the African American community.

Assessments and apologies

Across the nation, newspapers have conducted internal examinations and apologized for their racist coverage. In Kentucky, some newspapers responded to the Howard Center’s questions about their coverage of the 1908 reign of terror in Western Kentucky. Others didn’t.

Lexington Herald-Leader executive editor and general manager Peter Baniak said he wasn’t aware of how the newspaper covered lynchings in Western Kentucky. The newspaper did issue a front-page clarification in 2004 acknowledging its failure to cover the civil rights movement in Lexington. It updated the clarification in 2018.

Opinion columnist Linda Blackford, who wrote about the newspaper’s civil rights coverage, wasn’t surprised that the Herald and Leader spread rumors about the lynching of four Black men in Russellville.

“Newspapers were agents of the establishment back then,‘‘ she said. “I don’t think the Herald or the Leader represented the views of anyone but white people.”

Blackford said the impact of how newspapers covered or did not cover lynchings and the civil rights movement was “huge.”

“It nullified violence against Black people, and it justified basically terrorism,” she said

The newspaper is open to looking into previous coverage, Baniak said, citing the editorial board’s recent apology to a woman who integrated the Lexington public schools.

Some policies have also changed. Mugshots are no longer used as a matter of routine, and this year the newspaper started The Clean Slate, a pilot project that gives people who were arrested an opportunity to have stories about them re-examined and, in some cases, eliminated from the newspaper’s website.

The newspaper pays community members once a month to write opinion pieces about race, justice and education. However, diversity in its reporting staff is still a concern, Baniak said. The staff is 92% white, with 8% identifying as other races and ethnicities.

The Courier-Journal, the largest newspaper in Kentucky, decided to confront its past more than a year after Breonna Taylor’s death at the hands of Louisville police officers on March 13, 2020.

“We found the newspaper had a mixed record on race that depended largely on the era under review, reporter Andrew Wolfson wrote in a June 3, 2021, story.

The Bingham family, who owned The Courier-Journal from 1918 to 1986, issued an apology saying its shortcomings harmed Black lives and extended white supremacy in the community.

“We take responsibility for our harmful actions as individuals and for the actions taken by these companies. We are sorry and we offer our apology with our whole hearts,” the Bingham family wrote.

“Our constant refrain was ‘go slow,’ ‘don’t ask for too much at once,’ ‘don’t you see we’re trying to help you?’ and more of the like,” said historian Emily Bingham and her aunt, Eleanor Bingham Miller.

The Current and The Paducah Sun did not respond to the Howard Center’s requests for comment.

The Courier-Journal’s assessment did not resonate with Wright, the historian. “What happens in our society is that there are many instances of whites turning around and applauding themselves or other whites for doing the right thing only when forced to and when having no other choices in the matter,” he said.

Morrow, the SEEK Museum director, said apologies might not have the effect now they would have in the 19th century.

The real reckoning has yet to come, said Betty Baye, who spent 27 years as a reporter, editor and columnist for the Courier-Journal and is now a researcher for the University of Kentucky’s Civil Rights Hall of Fame Oral History Project.

“There seems to be no rest for the weary,” she said. “Each generation has to march, each generation has to protest because every time it looks like we are trying to get somewhere, there is some kind of movement that is against it.”