By Victoria Ifatusin, Gabrielle Lewis and Jamille Whitlow

SLOCUM, Texas — White men bought ammunition and stopped at saloons on a hot summer day in 1910 in Slocum, Texas. They had sheltered their wives and children in churches and schools. They believed a racial revolt was underway.

And so, they prepared to hunt Black people.

By that evening, “a race war was on,” the Palestine Daily Herald said. In 24 hours, about 20 Black people were dead.

“Some two hundred negroes had armed themselves … and were ready for trouble,” the newspaper falsely reported early on July 30, 1910.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

The violence, known as the Slocum Massacre , was incited by that rumored uprising — an uprising that never happened.

Yet white people, fearing an attack, surged through the streets of Slocum and shot Black people on sight, chasing them into nearby forests and marshes when the Black people tried to flee.

White-owned newspapers printed false news and used sensationalized language, promoting widespread racial terror.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

“Media is powerful, very powerful, and it can be used for good and evil,” said Constance Hollie-Jawaid, a descendant of one of the massacre’s survivors. “A race war is when two opposing forces agree to wage combat. That is not what it was. It was not a race war. It was an attack on innocent people, and we had no clue it was coming.”

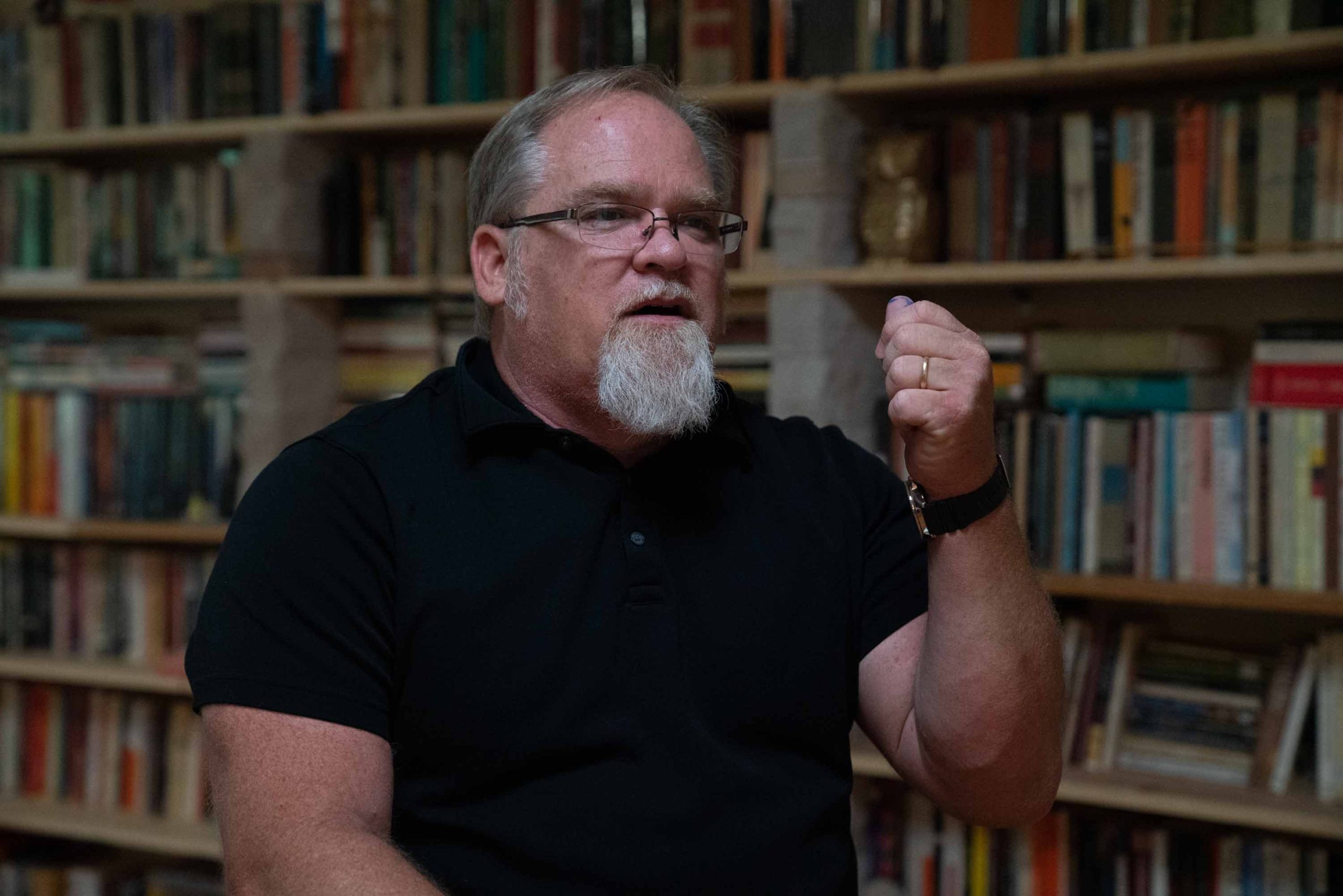

Hollie-Jawaid and E.R. Bills, a local author, say the Slocum Massacre has been ignored by the media and the nation.

Prospering after slavery

Founded in the 1890s, Slocum is about 130 miles from Dallas and home to fewer than 200 people.

After the abolishment of slavery, Black farmers moved onto Slocum’s bottomlands near Ioni Creek and Saddler Creek. White farmers gave Black people the land because they thought it less desirable and susceptible to flooding. Instead, the land was fertile, Bills said, and Black farmers thrived.

Hollie-Jawaid said her father would drive through Slocum and tell her about Jack Holley, her great-great-grandfather. He became a prosperous Black business owner in Slocum after coming out of slavery in Texas.

Holley, born in 1846, owned Slocum’s general store, a granary and a dairy. He also co-owned a bank with all-Black partners, Hollie-Jawaid said, and he was literate.

But Holley, his family and the entire Black community of Slocum became a target for white people, Bills said, when they saw the advancement of people who were once enslaved.

“White America often tells us to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps,” Hollie-Jawaid said. “But there should be a little asterisk for you to look at in the footnote that says, ‘But just don’t do better than we do.’”

Sparked by rumors

Two incidents preceded the violence, Bills wrote in his book , “The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas.”

The first was a quarrel between a Black businessman and a white farmer over a promissory note. The second was a county appointment that infuriated a white farmer: a Black farmer had been designated to get aid for county road repairs.

As word spread around Slocum, the reports of the promissory note quarrel morphed into a story about a Black man trying to cheat a white man. The news of the Black farmer’s appointment transformed into the tale of a Black overseer in charge of white crews. Combined with rumors of an uprising, these tensions convinced white people a race riot was imminent.

On July 29, 1910, white mobs of locals and residents from across Anderson County engaged in a “pot-shot occasion,” the Palestine Daily Herald reported. They moved from road to road, shooting Black residents along the way. When the victims’ bodies were found, they had personal possessions and bundles of clothing by their sides.

“People fled for their lives. People didn’t have time to bury their loved ones,” Bills said.

By the end of July 30, the violence had spread farther into Houston County. The white populace was terrified, the Palestine Daily Herald reported — though no racial uprising had occurred.

On Aug. 1, the Palestine Daily Herald reported the names of eight Black people who had been killed, two of whom were wounded and four of whom were missing. Others’ remains “will only be revealed by the buzzard.”

Bills does not believe the number of dead could be that low.

“Hundreds of white folks, hundreds of people in these mobs marching around — eight casualties?” Bills said. “One guy with a shotgun could’ve done that in one day.”

Damage control

When white-owned newspapers covered the massacre, they didn’t just publish false information. They also slanted their coverage to shift responsibility for the massacre onto Black people.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram wrote the massacre started because a Black farmer shot a white man over a debt — another distortion of the initial promissory note dispute. The El Paso Herald’s front-page headline, “TEN NEGROES ARE KILLED IN TEXAS RACE RIOTS,” was bigger than the newspaper’s name. (Scripps-Howard owned the El Paso Herald until it spun off all its papers in 2015. The Scripps Howard Foundation supports the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland.)

Bills said there is no evidence any white people were killed during the massacre, and they lacked any way to justify the terror they perpetrated.

“The newspaper coverage at that point, it became damage control just for the white folks,” Bills said. “The Black folks were leaving in droves.”

The Aftermath

Black people didn’t have time to take property deeds with them as they fled, Bills said. He said he believes white people later took the abandoned businesses and properties, including those that belonged to Holley, as their own.

“They wiped out the Slocum community,” Hollie-Jawaid said. “It was a primarily Black community and they rode in, walked in, drove in and killed everything Black and ran out everything Black.”

Many survivors fled Slocum with the intent of never returning, Bills said, to protect their families and avoid another killing spree. Many would either leave Texas or flee to nearby cities.

Jack Holley’s son, Alex, was one of the first victims of the massacre. Holley fled with his surviving family to Oakwood, about 30 miles away. Hollie-Jawaid said he changed the spelling of his surname to Hollie because he feared his family would still be hunted down.

‘Simply rumor and innuendo’

In April 1910, the census for the Slocum area — including two other communities in Anderson County — reported that Black people made up 30% of the community. By 1920, the Black population in Slocum had dropped to 15%. Today, the Black population is 7% of the community’s population. It is 20% or more in nearby towns.

“There are places in Texas where Black folks know not to go, and Slocum was one,” Bills said.

In 2014, Hollie-Jawaid and Bills applied to the Anderson County Historical Commission for a historical marker for the massacre. The commission rejected their request.

“Since we have absolutely no factual information but simply rumor and innuendo, I would recommend no action,” Jimmy Odom, who was chair of the commission, wrote in an email to its members. “Until there are substantiated facts to verify, I think it is highly inappropriate and dishonorable to accuse, even slander, people who are dead and cannot defend themselves.”

Greg Chapin, an Anderson County commissioner, sent a letter to Odom in 2014, writing, “Without further evidence of legal documentation, or the facts of guilty parties taken responsibility of the incident, Anderson County cannot accept the marker.”

In a 2014 interview with the Austin American-Statesman, Chapin said “it’s a sad situation,” but added that he felt “we’re all past it and other ones carry the burden on their shoulders.”

“Their ancestors dealt with it years and years ago, but some of them don’t let it go,” he said.

Chapin did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this article.

Eventually, Hollie-Jawaid and Bills received approval for a marker from the Texas Historical Commission. On Jan. 16, 2016 , the Tyler Morning Telegraph reported the historical marker was unveiled on State Highway 294 before a group of more than 200 people.

The pair said they want to identify mass graves, exhume the bodies and give them proper burials.

One suspected mass grave lies somewhere on what was the site of a Black man’s farm. The Fort Worth Record and Register reported on Aug. 1, 1910: “Farmers Gather Up Bodies and Dump Them Into Trench. No Further Trouble Is Anticipated.”

The second suspected mass grave is on private property near what used to be Silver Creek School, which Granville Hayes, a white man, identified in a letter to the Houston County Historical Commission in 1984. Hayes wrote that two men involved in the massacre told him they buried bodies at the school’s playground.

“They dug a common grave for some 8 or 9 black people and rolled them into it,” Hayes wrote, “and trampled the dirt so us kids playing over it would wipe out the evidence of them being buried.”

The suspected gravesite at the farm has not been found, Bills said, and Hollie-Jawaid has tried but failed to gain access to the private property suspected of holding the second gravesite.

‘The least we can do’

The Palestine Daily Herald lives on today as The Palestine Herald-Press. Jennifer Kimble, who was a reporter there, wrote several stories related to the massacre. She said nobody in the community wanted to talk about the violence, aside from Hollie-Jawaid and Bills. She also had to push her editors to understand the importance of the story.

“I was advocating to make this story go through. Nobody really knew what was going on,” Kimble said. “I had to do all the stuff and show them that this was a thing that needed to be in there, too.”

Today, the Palestine Herald-Press has four editorial employees: two reporters, one who is Black, and two editors.

After Kimble’s work in 2016, the newspaper didn’t write about the massacre again until Amy French, the editor, wrote an article on July 29, 2021, the anniversary of the violence.

PennyLynn Webb, the managing editor, said she knew of the massacre from Kimble’s work — but the rest of the staff, including French, did not.

“What got me was the fact that I’ve never heard of it,” French said.

French said she’s now read newspaper accounts. “It’s disturbing,” she said. “And you hate seeing (coverage) done like that.”

Jake Mienk, the newspaper’s publisher, said the paper strives to show diversity in its staff and stories.

“Newspapers must do a better job of reflecting the diversity of their communities throughout their products,” Mienk said in a statement. “We at the Herald-Press understand this and strive to show the diversity within our content as well as within our building.”

On July 30, 1910, the Palestine Daily Herald , like so many other white-owned papers, reported the rumor that an uprising had begun. Two days later, on Aug. 1, it explained it had received “exaggerated reports” and published a corrected story.

“In fact, newspaper reporters should be very careful to give only what seems to be justified by actual facts and let it go at that,” the paper wrote.

Mienk said “the Palestine Daily Herald was one of the few newspapers that reported accurately on the Slocum Massacre .”

Texas prides itself on being made of fair and decent people, said Bills, a Texas native. But he said some Texans should acknowledge Slocum’s horrific past..

“Acknowledgement is the least we can do,” he said. “Hopefully, we can change, and we can own up to our history … It’d be easier to live together if we were just honest about it.”