By Madison Peek

ELAINE, Ark. — When the Rev. J.R. Maxwell read the news about the Supreme Court case that came out of a tiny town in Arkansas, he could not hide his glee.

“It was like a thunder bolt from a clear sky,” wrote Maxwell, a member of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. “The NAACP is our only salvation.”

Maxwell’s letter written on Jan. 22, 1925, was one of several that flowed to the NAACP after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Moore v. Dempsey. The case reversed the death sentences of six Black men tried after a massacre killing hundreds of Black men, women and children in Elaine, Arkansas.

The highly publicized case had national implications. It allowed a sliver of optimism for Black Americans following the “Red Summer” of 1919, a period of racial terror in which hundreds of African Americans were killed by white mobs in 26 cities across the country.

Moore v. Dempsey would come to symbolize more than the six Black men saved from execution in Arkansas. It would leave a lasting legacy on the American criminal justice system, provide hope to Black Americans across the country and solidify the NAACP as the foremost civil rights group in the country.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

“It’s really one of the first victories when we start talking about anti-lynching,” said Brian Mitchell, a history professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

The case evolved out of a violent massacre of Black residents in the small, rural town of Elaine in Phillips County, Arkansas, after Black farmers attempted to unionize for better crop prices across four days during the fall of 1919.

Historians have established that between Sept. 30 to Oct. 3, five white people were killed. An unknown number of Black victims suffered brutal deaths. Reports range from 200 to 800 Black people slain by white vigilantes, federal troops and sheriffs and their deputies.

No white people were charged for the deaths of the Black victims, but more than 250 Black men were rounded up, jailed and tortured until they falsely confessed to being part of a plan to assault white residents in Phillips County, historians said.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

A group of powerful white business owners and officials, some of whom participated in the massacre, orchestrated the men’s torture and confessions, according to historians.

The group, dubbed the Committee of Seven, was appointed by Arkansas Gov. Charles Hillman Brough to investigate the massacre and received praise from white-owned newspapers.

“Phillips county has kept its record clean through the whole miserable trouble,” read an Oct. 9 editorial from the Arkansas Democrat. “The ‘Committee of Seven’ ought to have the heartiest support of every citizen of Phillips county in its efforts to protect all the prisoners in its care until they have received a fair trial and are convicted or freed.”

If the arrested men didn’t confess to being conspirators, the committee had them tortured by beating them with “leather straps with metal in them,” strapping them naked into electrified chairs and shoving “strangling drugs” up their noses until they confessed, according to a case brief filed in 1923 to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The case brief also detailed that during the initial trials, hundreds of white men gathered outside the courthouse with plans to lynch the jailed men.

However, a lynching was averted, because the soldiers and officials posted outside the courthouse assured them that the Black defendants would be found guilty and executed, historians said.

An all-white jury, white judge and white lawyers tried 122 Black defendants. Some jury deliberations lasted a mere two minutes, and several cases took under an hour, newspapers reported.

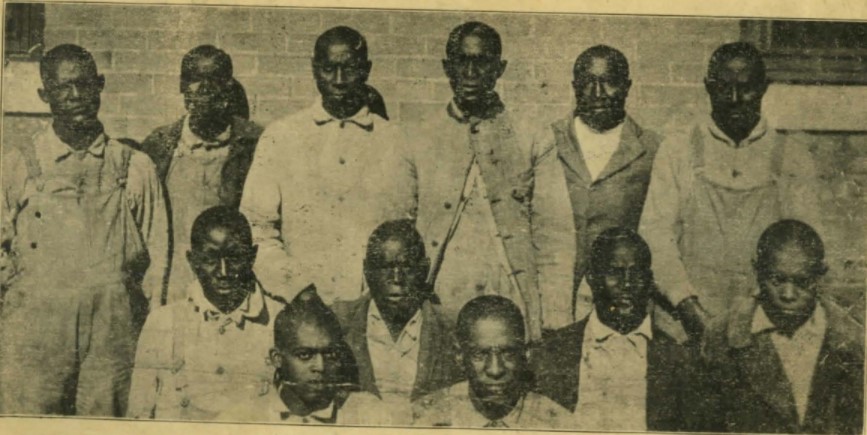

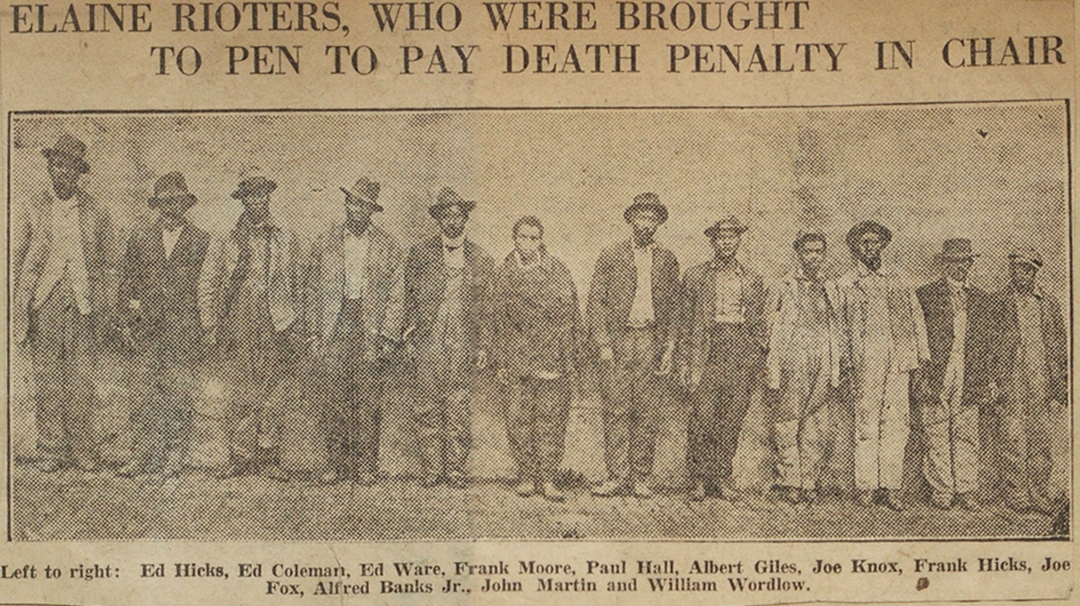

Records indicate 67 to 80 Black men were imprisoned for crimes ranging from “night-riding” to first-degree murder. Twelve men, who later went on to be known as the Elaine 12, were sentenced to death.

“The colored people here are strongly of the opinion that the convictions are a result of the white man’s idea that he will rule without any regard to popular majorities as long as that majority is not of the Caucasian race,” the Afro-American, a leading Black newspaper based in Baltimore, wrote in an editorial following the trials.

The Black press followed the cases closely, starting with NAACP investigator Walter White, a light-skinned, blue-eyed Black man who could pass for white. He slipped into Elaine to investigate the killings and for the first time gave voice to the Black victims.

His report on the massacre countered the dominant, false narrative carried by white media, including the New York Times, that placed the blame for the massacre on Black people.

“Investigation has thrown a searching light upon these stories and has revealed that the Negro farmers had organized not to massacre, but to protest by peaceful and legal means against vicious exploitation by unscrupulous landowners and their agents,” White wrote in his investigation.

His report was carried widely in Black-owned newspapers , including the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier and the Afro-American in Baltimore.

White took great risks by reporting in Elaine. According to White’s autobiography, a Black man in the nearby town of Helena, Arkansas, tipped him off that white men were looking to lynch the Black reporter who could pass for white, so White boarded the next train out of town. The train conductor told him about the plans with glee and said “When they get through with him he won’t pass for white no more!”

The Black press and its readers expressed outrage in a flurry of editorials and letters to the editor. The story attracted prominent Black journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who was an anti-lynching activist and a co-founder of the NAACP.

Wells-Barnett appealed to Black Americans in the Chicago Defender, asking for financial support for the men. One of the imprisoned men in Elaine saw her work and wrote to her.

Wells-Barnett boarded a train to Helena to speak to the imprisoned men. She took their accounts and prayed with them. She then went on to write “The Arkansas Race Riot,” a comprehensive investigation into what happened during the massacre that was published as a 62-page pamphlet in 1920.

“The terrible crime these men had committed was to organize their members into a union for the purpose of getting the market price for their cotton,” Wells-Barnett wrote. “These Negroes believed their chance had come to make some money for themselves and get out from under the white landlord’s thumb.”

She also wrote to the governor, who had ordered an estimated 500 to 600 National Guard troops to Elaine and reportedly chased some of the Black men himself during the massacre.

Wells-Barnett sent a resolution to Brough that said if the Elaine 12 were executed, the Black press would use its influence to get Black workers to leave Arkansas, which was dependent on their labor.

Brough, who today has come under fire for racist actions, told reporters at the time he was ignoring such threats and that he thought the trials were fair. Still, he stayed the men’s executions, so they could appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

The stayed execution provided an opening for the NAACP, which in 1919 was a much smaller civil rights organization than by today’s standards. It was founded just 10 years earlier. The NAACP had been watching the case closely, and with the Arkansas court’s ruling, it chose to intervene.

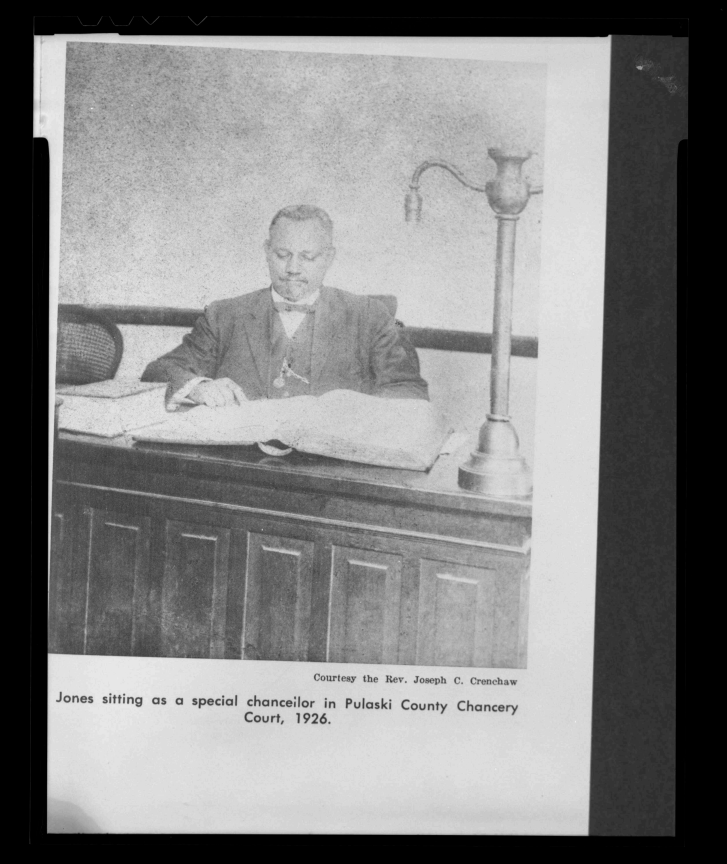

The NAACP hired Scipio Africanus Jones, a Black lawyer from Little Rock, Arkansas, who had made a name for arguing against unjust trials, and George W. Murphy, a white former Arkansas attorney general also from Little Rock.

The legal team also included Ulysses Bratton, a white lawyer hired by the Elaine Black farmers union before the massacre to secure better prices for their crops, and NAACP President Moorfield Storey.

The central argument of the legal defense was that the Elaine 12 did not receive a fair trial. The pressure of the mob, the inadequate defense council, the all-white courtroom and the quick hearings resulted in an unfair sentence, which went against the rights of the Black men guaranteed by the 14th Amendment, the lawyers argued.

The lawyers divided the Elaine 12 into two groups to get two chances to win in the Arkansas Supreme Court. One group of six was filed under defendant Ed Ware’s name, another group was filed under defendant Frank Moore’s name.

The Ware group won a reversal from the Arkansas Supreme Court, because the trial courts failed to specify if they were guilty of first or second-degree murder, according to court records. A legal ping-pong match between the local and state courts finally resulted in freedom for the six men in 1923.

The other six, however, had their sentences upheld. Jones and Murphy appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which denied their first appeal. Murphy died of a heart attack that very day.

Jones and the NAACP legal team kept fighting.

After three years of appeals, evidence gathering and barely evading the defendants’ execution date, the U.S. Supreme Court accepted the case.

Storey, a white lawyer and the NAACP’s founding president, appeared before the court on Jan. 9, 1923, to argue their case.

“They have been denied the equal protection of the law, and have been convicted, condemned and are about to be deprived of their lives without due process of law,” Storey said in a case brief presented to the court that was prepared by Jones.

The court ruled 6-2 for the NAACP and its defendants.

Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote for the majority.

“But if the case is that the whole proceeding is a mask — that counsel, jury and judge were swept to the fatal end by an irresistible wave of public passion, and that the State Courts failed to correct the wrong,” Holmes wrote, “neither perfection in the machinery for correction nor the possibility that the trial court and counsel saw no other way of avoiding an immediate outbreak of the mob can prevent this Court from securing to the petitioners their constitutional rights.”

John Burnett, a civil rights lawyer in Little Rock, said it was the right time and the right court for the right ruling.

“It’s a very prominent example of where they knew what was happening, out-and-out-racist mob-type violence,” Burnett said. “This marks the first occasion where you’ve got just enough people on the court and enough history behind them and enough things going on out in the country where they say ‘Well you know what, there is a limit.’”

Moore v. Dempsey marked the beginning of combating prejudice through the legal system, with the federal government involving itself in the state criminal procedure for the first time, Burnett said.

This opened the door to the legal revolution for civil rights in the late 1950s and early 1960s “just a little crack,” Burnett said.

But perhaps the greatest result of the case was the prospect of change it created among African Americans.

The decision and the freeing of the last six of the Elaine 12 in June 1925 provided a sense of possibility in the Black community. The Black press heralded the victory, and the Black community rallied around NAACP.

The Arkansas Survey, a Black newspaper based in Little Rock, wrote, “Scipio A. Jones, lawyer in charge of the defense in the Elaine case, has just brought that case to a successful conclusion. Not only do the colored people of Arkansas but all of the people of Arkansas owe to Judge Jones a debt of gratitude which they will never be able to pay to him personally.”

The Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “The decision of the Arkansas Supreme Court marks a real triumph, not only for the organizations which interested themselves so unsparingly, but for the entire race.”

Letters poured into the NAACP offices from African Americans all over the country, from “school teachers, doctors, lawyers, who are in support of the efforts that are being made by the NAACP,” Mitchell said.

White Americans also offered their praise and support.

“With you, I rejoice in the conclusion,” wrote Dr. Charles F. Thwing, the president of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “I am glad to help in the future according to my little ability. Of course, my little ability is no measure of my deep interest.”

With its national status elevated, the NAACP became hope for African Americans across the country.

But for the Elaine 12, there was no celebration.

Much remains unknown about what happened to the men after they were freed from prison, though descendants and historians have attempted to fill in the gaps.

Through his research at the University of Arkansas, Mitchell has pulled a variety of records, death certificates and other sources together and traced what happened to six of the 12 men.

Mitchell said his research showed some moved to Illinois, Louisiana and Missouri. Some of their wives moved on and remarried while they were imprisoned. Others waited for their husbands to return home. The majority died very shortly after being freed, he said.

Lisa Hicks-Gilbert is a descendant of Ed and Frank Hicks, two of the men sentenced to death. Hicks-Gilbert, a 53-year-old freelance paralegal who is the great-great granddaughter of Ed Hicks, said the two brothers took different paths after they were released.

Frank moved to Illinois, she said. Ed stayed in Arkansas. She said the two never spoke to each other again. The family believes Frank changed his name and died childless, according to Hicks-Gilbert.

All of the men, despite going their separate ways, had one thing in common. Despite their victories in the U.S. Supreme Court and the Arkansas Supreme Court, they were still found criminally responsible for crimes during the Elaine Massacre under Arkansas state law.

Mitchell explained that when the publicity surrounding the cases became too much, Arkansas Gov. Thomas McRae granted the men clemency. They freed the men but did not clear their records.

Hicks-Gilberts, along with other organizations, has tried to win exonerations for the 122 convicted men, but the state has rejected their efforts.

Although the state has made efforts to memorialize Ed Hicks by offering to put a marker on his grave, Hicks-Gilbert said the family wished the state spent the same energy to exonerate the convicted men.

“Until this state does what is right, then a marker to them is an insult,” she said. “Take that time and free us.”