By Airielle Lowe

The 1947 lynching of Willie Earle in Greenville, South Carolina, by some accounts the state’s last, was just like so many others.

Acting on hearsay, a white mob took the law into its own hands, broke Earle out of jail, killed him, and left his body by the side of a road. Then, they went home and back to work the next day.

But three months later, news reporters from around the nation descended on the textile town of about 60,000 for the trial of the accused — 31 white men who had been promptly arrested and charged with killing a Black man in a state where murder was a capital crime.

Prosecutors had statements from 26 men acknowledging their own and one another’s involvement in a conspiracy to lynch Earle. Five had identified the one who fired the shotgun blast to Earle’s head that ended his life.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

Black-owned newspapers were encouraged by the swift round-up and hopeful for a reckoning long overdue.

“This is good detective work anywhere but is remarkable in South Carolina, where the arrest of a lyncher is virtually unknown,” The Pittsburgh Courier reported. The Atlanta Daily World heralded a “good start” that could be “the beginning of a change of heart in southern communities to blot out the lynching evil.”

But a skillful defense team outmaneuvered the prosecution, and time and again, the judge ruled in its favor on pivotal matters of law. Not a single man was convicted of a single crime.

The trial lasted 10 days; all the jurors were white. An editorial afterward in The New York Times said state and local officials “did their utmost to bring Earle’s slayers to justice, and … they had the support of the local press, the local ministers and a strong body of opinion throughout South Carolina.”

“A precedent has been set,” the editorial read. “Members of lynching mobs may now know that they do not bask in universal approval, even in their own disgraced communities, and they may begin to fear that some day, on sufficient evidence and with sufficient courage, a Southern lynching case jury will convict.”

An opinion column in The Courier weeks later was less optimistic. It was written by Benjamin E. Mays, then the president of Morehouse College in Atlanta. One of his students at the time was Martin Luther King Jr.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

“What happened to Willie Earle may happen to any Negro,” Mays wrote. “The Negro has no rights in many areas which the white man is bound to respect. How long, O God, how long, will a man be treated worse than a beast just because his skin is black!”

An unsigned opinion article in the Afro-American was accompanied by a photograph of Earle’s mother, Tessie, suggesting what she might say as the trial was ending:

“Study this mother’s face, her firm chin, her fighting eyes, and read there a determination which seems to say, ‘I will not give up. I will fight on.’ Read there the unspoken command to other mothers of color to unite. ‘This is my boy,’ she says, ‘but it could have been your boy, because the same brutality that killed mine may some day ensnare yours.’”

That fear would be voiced anew more than 60 years later.

“When Trayvon Martin was first shot, I said this could’ve been my son,” President Barack Obama said after Martin was killed by a neighborhood watchman in 2012. “Another way of saying that is, Trayvon Martin could have been me, 35 years ago.” The 44th president was born in 1961, 14 years after Earle was killed.

In the end, coverage of the events left Greenville and the nation uncertain about what happened and what had not, according to William B. Gravely, who studied the trial based overwhelmingly on contemporary news media accounts. There was no official transcript of most of the proceedings.

“On one level, the public [perception] was, this was progress because you had arrests, even though you didn’t get a conviction. There was also great regret and confusion about how you could have this happen? How could you have confessions and not a conviction,” Gravely said in an interview this year.

Gravely’s book, “They Stole Him Out of Jail: Willie Earle, South Carolina’s Last Lynching Victim” and its narrative of the trial and the trial’s aftermath, are cited frequently in this article, along with his observations.

In recent years, no local or national newspapers have been called out for encouraging or outwardly supporting the lynching of Earle in their coverage. Others in the South have for other cases, including in North Carolina and Alabama.

The Greenville News, Earle’s hometown newspaper, published a comprehensive retrospective of the lynching and the trial in 2003 and reprinted it in 2018.

“Greenville was not maybe seen as the epicenter for violence against Black people in that era, but it was not innocent of it either,” said Steven Bruss, executive editor of The News, which is now owned by Gannett, the nation’s largest newspaper group.

“The Greenville News is not innocent at all in its lack of using racist terms and writing racist editorials. Our newspaper has done those things, and it is something that we need to reckon with as a publication,” Bruss said in a recent interview.

“If we get to a point where an apology is the right thing to do, we need to make sure that that apology is comprehensive as well, and that we do it in a way that is meaningful to the Black communities of Greenville and throughout the country, and not do it in a way that rings hollow.”

Much of what took place in and out of the courtroom and what was said by public figures and in the press, has echoed recently in issues around police accountability, hate crimes and gun violence, including earlier this year in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd.

Chauvin was convicted of murder because of the eyewitness account provided by cell phone video shot by a 17-year-old bystander that allowed the world to see him killing Floyd.

The videographer, Darnella Frazier, received a Pulitzer Prize special citation this year “for courageously recording the murder of George Floyd, a video that spurred protests against police brutality around the world, highlighting the crucial role of citizens in journalists’ quest for truth and justice.”

The year before, a special citation was awarded posthumously to Ida B. Wells-Barnett “for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

Eliminating eyewitness accounts of the murder of Earle was only a tactic in the defense’s courtroom strategy. The goal was not to deny that any identifiable person had killed Earle, but rather to prove that there was nothing wrong with killing him.

The defense attorneys “had no plan to establish alibis or to have men swear that they did not mean to be part of something that ended in murder,” Gravely wrote. They “would not pretend that any member of the lynching party naively believed that the journey to [abduct him] had any other goal than to kill Willie Earle. [They] would brazenly assert that these men did the right thing and that they should be exonerated.”

Rebecca West, a court reporter and novelist from England who covered the trial for The New Yorker magazine, put it this way in her notes, Gravely wrote: “They didn’t kill the man because he was a Negro, but they thought they wouldn’t be punished because he was a Negro.”

Such was the way of the South, a way that it wished outsiders — especially those in the North—would just let be. Mays, the Morehouse president, said no.

“As long as the South lynches and condones it, the South will not be left alone,” he wrote in The Courier. “When a people act in an uncivilized, undemocratic and un-Christian manner, it will be and should be criticized.”

Abducted

It was in the predawn hours of Feb. 17, 1947, that several dozen white men abducted Willie Earle, 24, from the jailhouse in Pickens County, South Carolina, and killed him, after hearing that a Black man had stabbed and robbed a white taxi driver.

“The negro should be taken out and given the same thing he had given” the taxi driver, a dispatcher later told investigators he overheard one angry driver tell others before a mob of drivers went to the jail. Witnesses said they first stabbed Earle several times and hit him in the head with the butt of a gun.

Then, “Give me the gun, let’s get it over with,” one of the killers said, before firing two blasts into Earle’s body. Five witnesses later identified the shooter by name.

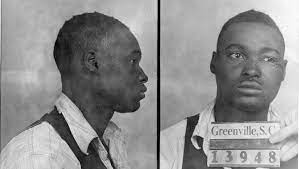

A police department headshot of him, along with those of 29 others, accompanied a front-page article in The Greenville News headlined, “31 PERSONS CHARGED WITH MURDER IN LYNCHING OF NEGRO.”

“During the afternoon,” The News reported, “practically every cab driver in Greenville not [already] in jail was rounded up and brought to Greenville police headquarters for questioning, as officers neared the end of their investigation.”

The newspaper time-stamped the charges: “almost exactly four and a half days after Earle was whisked away from the Pickens county jail and shot and slashed to death on the Bramlett road 4.2 miles from Greenville.”

The charging documents were similarly specific: The men “did commit the offense of murder,” the papers declared. After coming together as a mob, they removed Earle from legal custody. They brought him across the county line “and then and there did shoot, cut, stab, beat and bruise the said Willie Earle, thereby mortally wounding him, and as a result of said wounds the said Willie Earle did then and there die.”

The swift investigation, arrests and charges stood in sharp contrast to countless past incidents where lynchers remained nameless, faceless and out of court.

A newspaper publisher in nearby Anderson praised Greenville law enforcement officials for having “done more to stamp out lynching in this state than all the newspaper editors and preachers who have fought the practice for years,” Gravely wrote.

The investigations, mostly the work of the FBI, resulted in numerous incriminating statements from those charged, who had been interviewed at a time when persons questioned were not routinely warned that what they would say during interrogation could be used against them later in court.

The lead prosecutor, Robert T. Ashmore, planned to do just that — he would cast the defendants as incriminating witnesses, one against another. All played a significant role in abducting and killing Earle and all should be convicted, he would argue. Gravely referred to this conspiracy-based approach as Ashmore’s “the hand of one is the hand of all” courtroom game plan.

On trial

The trial began on May 12, 1947. The first key event in the lynching was Earle’s abduction from the jail, where he was being held overnight — not charged with murder, but more like a person of interest to be questioned about a reported robbery and stabbing. At the time that Earle was killed, the man whom some early news reports said he had killed was still alive.

The cab driver, Thomas W. Brown, had described the encounter. “He took my cab and my money,” he said while waiting for the ambulance. At the hospital, he identified the robber “only as ‘a large Negro,’ not a description of Earle’s size,” and not the same as identifying Earle specifically or by name, Gravely wrote.

Earlier on, newspapers had reported inaccurately that Brown had been shot, and the lead defense attorney eventually used that inaccuracy to help him make the trial about Earle killing the taxi driver instead of the mob killing Earle.

The Pickens County jailer, J. Ed Gilstrap, took the stand as a witness, not a defendant, even though allowing Earle to be taken by the mob could be seen as a violation of his legal obligation to protect a prisoner in his custody.

Gravely said state and local prosecutors were uncertain they could win a conviction of Gilstrap, and pressing such a case could lead to greater federal involvement. Prosecutors wanted to assert the state’s right to prosecute its own for state crimes, not national ones.

In interviews immediately after the killing and before the trial, Gilstrap, the jailer, had told reporters and investigators that when confronted by the mob, he feared for his life if he didn’t let them take Earle.

“The men were not masked, Gilstrap said, although he said he did not recognize them,” the Associated Press reported. “Several of them carried shotguns and most of them wore caps,” the article read.

Gilstrap “estimated that [the men] rode in several automobiles” as they drove off, the article said. “Some of the automobiles may have been taxis”

On the stand, the jailer repeated his vague account.

One of the participants in the lynching previously told FBI investigators that he recognized Gilstrap, and had told that to others on the way to the jail.

Yet, when the chief defense lawyer said to the witness on the stand, “You couldn’t identify a single soul,” Gilstrap replied, “No, sir.”

A murder conviction required proof of intent, and the prosecution hoped to show that the mob intended to punish Earle for what he had done. Its evidence for doing that came from newspaper reports that were demonstrably false.

Shortly after the killing and “out of the blue,” Gravely wrote, “stories began to claim that Earle shot his victim and ‘had been arrested as the result of a beating [a claim never made] and robbing [a crime never solved]” of the cab driver.” (The brackets are the author’s.)

That inaccurate information was repeated in the course of the trial. “Gunshots, which took Earle’s life, became a new projection onto him as additional violent behavior” against the cab driver, instead of the mob’s violence against Earle, Gravely wrote.

Having indicted Earle on its own, the mob needed a trial or a confession to justify its sentence. Eight members of the mob said they had heard Earle “own that he had stabbed Brown,” Gravely wrote.

A turning point in the trial came when defense lawyers asserted that any defendant’s statement made before the trial could not be used against another defendant during the trial. That effectively undercut the argument that Earle’s abduction and killing was a conspiracy, since by law, a conspiracy must involve more than one person. The judge agreed.

That agreement also undercut the state’s courtroom strategy. “The prosecution was thus left without the power of the confessions in depicting the acts of other defendants,” Gravely wrote.

The defense also asked that the names of the defendants be stricken from the court record. The judge again agreed, declaring that the defendants in the courtroom were not the people charged with murder in the court documents, even if they actually were.

The collapse of the case in court was not exactly a surprise to the prosecutors, whom Gravely spoke with years after the trial. The witnesses’ accounts of what happened were inconsistent. “You had such contradictory statements from 26 different perspectives,” he said.

Even before the trial, Ashmore, the chief prosecutor, “made the assumption that he could not get a conviction” for murder, only conspiracy, Gravely said, and Ashmore “didn’t want these guys to be badly punished.” Instead, “he wanted to slap [them] on the hand and make a moral judgment, but not much like a legal judgment that had consequences.”

The key remaining question was who murdered Willie Earle? Quoting from local newspaper accounts of the trial, Gravely described the courtroom testimony of the man accused of doing it, Roosevelt Carlos Herd Sr.

“With the confessions having twice been read into judicial records weeks earlier and reported in the press, anyone locally and many people nationally knew as early as March 4 that Herd had been identified as the triggerman,” Gravely wrote.

“The most chilling moment,” he wrote, “came when these words, attributed to Herd, rang out:

‘They then drug the negro out of the car, and they brought him out behind our car and between the next car and everybody started beating him. They knocked him down on the side of the road’.”

“Next came the climax everyone anticipated,” Gravely continued. “He finished, ‘Somebody fired a gun. I did not have a gun, and I don’t know whether the shots hit the negro or not. When I seen they were going to kill the negro I just turned around, because I did not want to see it happen’.”

Prosecutors made one last attempt to present the killing of Earle as an intentionally brutal and terrorizing act—the generic definition of a lynching. They asked if they could show the jury photographs of Earle’s corpse because, they argued, “the mutilation of the body shows malice in the heart of the killer,” Gravely wrote. The photos were so gruesome, Gravely wrote, that Earle’s mother told an interviewer “she didn’t want to see his body in the mortician’s parlor” after viewing them.

Thomas A. Wofford, the chief defense lawyer, objected. To show the photos, he said, would be “highly prejudicial,” Gravely wrote. “Wofford contended that they [the photos] ‘don’t prove a thing except the n—– is dead, and everybody knows that’.” The judge upheld Wofford’s objection.

Some newspapers quoted Wofford as saying “the negro is dead.” Gravely said during the interview that he had decided to include in the book “even the offensive terms” used in some newspaper accounts “in order to depict the period.”

The News reported highlights of closing arguments on May 22, 1947, the morning that the case went to the jury in the General Sessions court, with Judge J. Robert Martin Jr., presiding.

“Despite his clearly-stated ruling that no racist issue was to be injected into remarks by the attorneys making arguments in the unprecedented mass trial, defense counsel several times made such remarks, which were quickly ruled out of order,” the article noted.

Chief defense counsel Wofford reminded the jury of how Earle’s body had been found. “It took a n—– undertaker to find there had been a lynching.” And another defense attorney, John B. Culbertson, offered no remorse for what happened. “Willie Earle is dead, and I wish more like him were dead.”

Wofford also criticized federal investigators who had conducted many of the interrogations that resulted in the defendants’ statements, saying the FBI had been “suffering from a malady … that’s what I call meddler’s itch.”

“We people get along pretty well,” he said, “until they start interfering with us in Washington and points north.”

The jury found the defendants not guilty, on all counts.