By Anuoluwapo Adefiwitan, Julia Arbutus, Molly Cuddy & Lindsay Garbacik

Billie Holiday looks at the stage floor, then takes a deep breath. She gazes straight into the audience and begins to sing, “Southern trees bear a strange fruit./ Blood on the leaves. And blood at the root.” Her shoulders seem to slope under the weight of the song so haunting, it leaves the audience entranced. “Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze. Strange fruit hanging from the poplar treeeeeeeeeesssssss.” As she lets go of the final “s” of trees, the word lingers.

In this 1959 performance in Chelsea, London, Holiday bends the words as she sings, adding syllables, embodying the melancholy lyrics. She seems transformed, as she transports the audiences into the horror of lynchings.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

She sings, “Pastoral scene of the gallant south.” Her shoulders cave. She appears repulsed as she sings, “The bulging eyes.”

Then her face contorts and she sings, “and the twisted mouth.” Demonstrating her masterful jazz technique of phrasing and inflection, she sings, “the scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh.”

Her voice resonates, as she releases a coarse and brassy, yet lyrical, sound. She chops the words, “Then the sudden smell of bur—ning flesh.” The piano chases the lyrics. Holiday takes her time in conveying the horror. Singing slowly, ever so slowly, allowing each note to permeate the silent room.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

The veins on the side of her neck strain. Seemingly nauseated, she continues:

“Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck.”

“For the rain to gather.”

“For the wind to suck.”

The piano pops.

“For the sun to rot. For the tree to droooooooooooop,” Holiday sings, allowing the words to descend.

“Here is a strange...” She spat out “and bitter...” Holiday’s twisted mouth mimicked the cries of lynched bodies as she sang for the length of two ascending notes, “crooooooooop!”

HOW ‘STRANGE FRUIT’ CAME TO BE

Holiday premiered “Strange Fruit” in 1939, at the height of Jim Crow, the laws that enforced racial separation in America from 1877 to the mid-1960s. The soul-wrenching song was publicly introduced on a March night in one of the first integrated clubs in New York City, Café Society on Sheridan Square, according to Julia Blackburn, author of “With Billie.”

“It was during my stint at Cafe Society that a song was born, which became my personal protest—‘Strange Fruit,’” Holiday wrote in her autobiography “Lady Sings the Blues,” which was published in 1956 and co-written by William Dufty.

“I was scared people would hate it. The first time I sang it I thought it was a mistake and I had been right being scared. There wasn’t even a patter of applause when I finished. Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everyone was clapping. It caught on after a while and people began to ask for it.”

By 1939, Holiday was a star, a jazz great with a voice so beautiful that she packed clubs with white and Black audiences. She sold tens of thousands of records and peaked on the pop charts. “Strange Fruit” reached number 16 on available pop charts for 1939. The version Holiday recorded for Commodore Records became her biggest-selling record, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

Even as Holiday’s jazz stardom grew, her influence as an early civil rights activist became overshadowed by the press’s reluctance to print anything but her run-ins with the law.

“They would write about Billie being a drug addict,” Blackburn said. Holiday dealt “with her fear of racism and her fear of being intimidated and incarcerated by singing her songs, and ‘Strange Fruit’ was the cornerstone.”

“She was a high-profile figure, and they wanted to break her,” Blackburn said. “She had to be made into a useless, drug-taking, stupid woman, because that then stops the power of this song.”

BILLIE HOLIDAY’S EARLY YEARS

Holiday was born Eleanora Fagan in Baltimore on April 7, 1915, according to her autobiography. Some records show she was born in Philadelphia. Her mother was 13 years old and her father was 15 when she was born. “Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when they got married. He was eighteen, she was sixteen and I was three,” according to her autobiography, “Lady Sings the Blues.”

“After they were married awhile we moved into a little old house on Durham Street in Baltimore.” Her father had dreams of playing the trumpet, but was drafted into the Army and sent overseas where “it was just his luck to be one of the ones to get it from poison gas over there,” she wrote. “It ruined his lungs.”

After he returned home from war, “Pop hit the road, the war jobs were finished and Mom figured she could do better going off up North as a maid.” Her parents left her to be raised by her grandparents in a house where her cousin Ida, her two small children, Henry and Elsie, and her great-grandmother, also lived. “All of us were crowded in that little house like fishes. She recalled that her great-grandmother had been born enslaved on a plantation in Virginia. “We used to talk about life,” she wrote. “And she used to tell me how it felt to be a slave, to be owned body and soul by a white man who was the father of her children.”

As a teenager, Billie scrubbed steps in Baltimore to make money. She loved to sing and heard her first “good jazz in a whorehouse.” She began hanging out at a “whorehouse on the corner nearest our place,” where she ran errands for the owner, washing basins, putting out Lifebuoy soap and towels. She told the owner of the house that she would work for free, as long as “she’d let me come up in her front parlor and listen to Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith on her victrola.”

A “whorehouse,” she wrote, was the only place “where black and white folks could meet in any natural way. They damn well couldn’t rub elbows in the churches. And in Baltimore, places like Alice Dean’s were the only joints fancy enough to have a victrola and for real enough to pick up on the best records.” When she could, Billie would slip into movie houses to watch films. She was a big fan of the actress Billie Dove, whom she would name herself after. “My name, Eleanora, was too damn long for anyone to say,” she wrote. “Besides, I never liked it. Especially not after my grandma shortened it and used to scream ‘Nora!’ at me from the back porch.” Her father began calling her Bill “because I was such a young tomboy.” She liked the name. “But I wanted to be pretty, too, and have a pretty name. So I decided Billie was it and I made it stick.”

Holiday had a tough childhood, between her cousin Ida, who would beat her with “her fists and whips,” and a man, whom she identified as “Mr. Dick,” raping her when she was a child. “It is the worst thing that can happen to a woman,” she wrote. “And here it was happening to me when I was ten. When her mother, who was at the hairdresser, found out a man had taken Billie down the street into a house, she tracked the man down and called the police.

The man was sentenced to five years for the rape. Billie, still a little girl, was not treated by the justice system as a victim. Instead, she was sentenced to a Catholic reform institution. “When you did something against the rules at that place,” she wrote, “at least they didn’t beat you, like Cousin Ida had. When you were being punished you got a raggedy red dress to wear. When you wore this dress, none of the other girls were supposed to go near you or speak to you.” Billie wrote that one day she was punished, required to wear the ugly red dress and locked in a room with a girl who had died. “I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t stand it. I screamed and banged on the door so, I kept the whole joint from sleeping. I hammered on the door until my hands were bloody,” she wrote. The next time her mother came for a visit to the institution, Billie demanded to be released. “According to the judge, I was supposed to stay there until I was dead or twenty-one,” she wrote. “But they finally got me out.”

Billie’s mother had moved to New York. When Billie was 13 years old, her mother sent for her to join her there. Her grandmother packed her a bag of fried chicken and hard-boiled eggs and she rode the train to Harlem.

Her singing debut was at a club named Pod’s and Jerry’s, an after-hours spot in Harlem. When she walked in, she was desperate for a job to pay the rent for her mother. “I think I talked to Jerry. I told him I was a dancer and I wanted to try out. I knew exactly two steps, the time step and the crossover. I didn’t even know the word ‘audition’ existed,” Holiday wrote. . The owner sent her over to the piano and told her to dance. “I started, and it was pitiful,” Holiday recalled. “I did my two steps over and over until he barked at me and told me to quit wasting his time.”

The owner was going to throw her out, but she said she kept begging for a job.

“Finally the piano player took pity on me. He squashed out his cigarette, looked up at me, and said, ‘Girl, can you sing?’”

Holiday told him she could. She’d been singing all her life, but thought she couldn’t make a living from singing. “Besides, those were the days of the Cotton Club and all those glamour pusses who didn’t do nothing, but look pretty, shake a little, and take money off tables,” Holiday wrote. She asked the piano player to play “Trav’lin’ All Alone.” The whole joint quieted down. “If someone had dropped a pin,” Holiday wrote, “it would have sounded like a bomb. When I finished, everybody in the joint was crying in their beer, and I picked thirty-eight bucks up off the floor. When I left the joint that night I split with the piano player and still took home fifty-seven dollars.”

Holiday’s singing led her to Café Society nightclub in New York City, where she sang for nine months. Through Café Society, Holiday met Abel Meeropol, a Jewish poet and high school teacher who was a Communist. According to Meeropol, he wrote a poem called “Bitter Fruit” in response to viewing a photo of a lynching, and he was invited to Café Society to play it for Holiday.

Holiday said the song reminded her of her father’s death after he was denied medical treatment for a lung disorder due to racial prejudice.

“When he showed me that poem I dug it right off. It seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop.”

According to the Library of Congress, Meeropol, a poet, teacher and songwriter, wrote “Strange Fruit” under his pseudonym, “Lewis Allan,” and also wrote “The House I Live In,” which Frank Sinatra sang, and “Apples, Peaches and Cherries,” performed by Peggy Lee.

Holiday explained that she, Allan and accompanist Sonny White worked on the music, turning the poem into a song. “So the three of us got together and did the job in about three weeks,” Holiday wrote. She was assisted by Danny Mendelsohn, another songwriter. “He helped me with arranging the song and rehearsing it patiently. I worked like the devil on it because I was never sure I could put it across or that I could get across to a plush night-club audience the things that it meant to me.”

Holiday continued to perform the song, as she traveled. Singing the song depressed her and made her physically ill. “But I have to keep singing it, not only because people ask for it,” Holiday wrote, “but because twenty years after Pop died the things that killed him are still happening in the South.”

One night after she performed “Strange Fruit” at the Downbeat Club, on West 52nd Street in Midtown, she wrote, she ran off the stage and raced to the women’s room. “When I sing it, it affects me so much I get sick,” she wrote. “It takes all the strength out of me.”

A woman followed her and found her in the women’s room all “broken up” and crying. “She looked at me, and the tears started coming to her eyes,” Holiday wrote. “‘My God,’ the woman told her. “I never heard anything so beautiful in my life. You can still hear a pin drop out there.”

THE WHITE PRESS COVERED HOLIDAY’S ADDICTION, BUT AVOIDED ONE OF HER MOST FAMOUS SONGS

On April 20, 1939, just a few months after Holiday’s first performance of “Strange Fruit” at Café Society, she received special permission from her record label to record the song with Commodore Records, which, unlike her label, was willing to take on the social content of the song. Soon after, “Time” magazine published a review that seemed more concerned with Holiday’s appearance than “Strange Fruit” itself.

The review called the song “a prime piece of musical propaganda” for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and even began with a comment about Holiday’s body shape, calling her a “roly-poly young colored woman” and saying “she doesn’t care enough about her figure to watch her diet, but she loves to sing.”

Other newspapers followed the magazine’s lead, calling “Strange Fruit” propaganda, and some radio stations refused to play the song. The Daily News in New York reported when a radio station did broadcast the song, because it was so unheard of. “For the first time since the anti-lynching song ‘Strange Fruit Grows on the Trees Down South’ was written, a radio station has agreed to broadcast it,” the paper wrote. “Although other studios have frowned on the number, WNEW has given its consent to the airing of the bitter song.”

David Margolick, the author of “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song,” said white papers rarely addressed “Strange Fruit” because it was about a racist terror lynching.

“It was just too sensitive a topic, and concerned Black culture and history, things that White America barely acknowledged anyway,” Margolick wrote in an email.

Though dozens of white newspapers did not broach the topic of “Strange Fruit,” they seemed eager to discredit Holiday when law enforcement began pursuing the singer for her drug use.

“It was critical [to her downfall],” said author and historian C.R. Gibbs of the white press’s coverage of Holiday. “It seemed as though it was with some joy that they began to turn on her when her issues with substance abuse started. She just was considered a rabble-rouser, or the song was.”

In 1947, Holiday was arrested for the first time on a charge of narcotics possession, found guilty and sentenced to one year and a day in the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, Blackburn writes in “With Billie.” After her release, the New York Police Department stripped Holiday of her cabaret performer’s license, barring her from singing in nightclubs and other venues that served alcohol, even as other nightclub employees with arrest records kept their employment.

After her release from prison, The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph dedicated a whole page to Holiday, detailing her comeback.

“Never wavered even when a little more than a year ago she sank to the level of New York’s drug rings,” the article said. It highlighted how willing her fans were to support her once again. “When she finally came out, freed of the drug plague and ready for whatever other punishment a fickle public might decide upon, they packed Carnegie Hall to the street to hear her sing just ten days after she became a free woman again.”

In 1948, The Dayton Herald published a review of Holiday’s performances. “Some time ago Billie, who is gorgeous in a flaming red dress and pallid white gardenias, strayed in the direction of drugs and such,” Herald critic Alice Hughes wrote. “ Then she pulled herself together, underwent a cure and is now back on stage.”

Hughes criticized Holiday’s admirers. “They all praised Billie Holiday,” Hughes wrote, “But to me she seems small-talent-and-all-buildup.”

BLACK NEWSPAPERS GIVE ‘STRANGE FRUIT’ MORE PRESS

Many Black-owned newspapers covered Holiday like the jazz phenom she was.

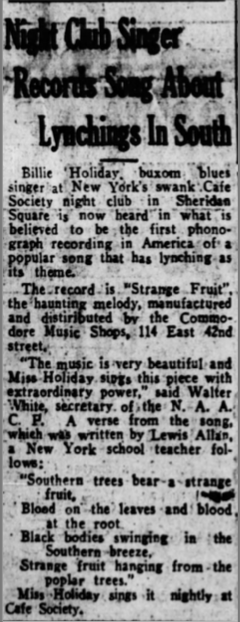

“The New York Age,” one of the most prominent Black papers at the time, wrote a column on June 17, 1939, that included lyrics from the song and a location where the recorded version of the song could be purchased.

“Billie Holiday, buxom blues singer at New York’s swank Cafe Society Nightclub in Sheridan Square is now heard in what is believed to be the first phonograph recording in America of a popular song that has lynching as its theme,” the newspaper wrote. “Miss Holiday sings it nightly at Cafe Society.”

Walter White, secretary of the NAACP, is quoted within the newspaper’s coverage as saying, “The music is very beautiful, and Miss Holiday sings this piece with extraordinary power.”

HOW THE FBI PURSUED BILLIE HOLIDAY

Holiday’s publicly available FBI file is just nine pages, three of which are newspaper articles from 1949 discussing charges against Holiday for narcotics possession.

The newspaper clippings were “a way to track her,” Gibbs said. “The Black community is almost uniformly behind her, which makes the song and artist a threat, at least to some people, like the FBI.”

While the public FBI file begins and ends in 1949, the FBI began compiling information on Holiday in 1940, just after she first sang “Strange Fruit” at Café Society, according to Blackburn.

A “source states that Holiday and [John] Levy [Holiday’s husband] are known users of narcotics and have been under close investigation by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics during their tour while in Utah and California,” according to a memo sent to FBI inspector John Mohr.

America’s first drug war was spearheaded by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Harry J. Anslinger, the bureau’s first commissioner, from the 1930s to the mid-1960s, according to Matthew Pembleton, author of “Containing Addiction: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the Origins of America’s Global Drug War.”

It was during this time that the Federal Bureau of Narcotics began looking into Billie Holiday for drug use, a battle that was made into the subject of the 2021 movie, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.” The movie dramatizes the FBN’s investigation into Holiday and implies that the agency was invested in arresting her to stop her from singing “Strange Fruit,” as well as to make an example of her as a drug user.

“The Bureau, for example, was notorious for hounding jazz musicians; attacking jazz as a carrier of addiction was an indirect way of addressing [B]lack drug use,” Pembleton writes. Anslinger played up the arrests and overdose of Billie Holiday in FBN publications, Pembleton wrote.

Through it all, she kept singing “Strange Fruit,” even though her co-writer Dufty believed her run-ins with the law could have been prevented if she had stopped singing the protest song.

“She has been kicked around and harassed for years by the authorities,” Dufty is recorded as writing in a letter to a lawyer in Blackburn’s book “With Billie.” “One of the reasons is that this song Strange Fruit made her well-known and controversial.”

“‘At any one of a hundred points in recent years she could have gotten off easy if she had merely told the FBI or other government investigative authorities … that she didn’t know what the song meant,’” Dufty continued.

In her autobiography, Holiday explained how she was able to infuse the song with deep emotion. During a two-week stint in Miami during the mid-1950s, Holiday said, she did not sing the song. “I was in no mood to be bothered with the scenes that always come on when I do that number in the South,” Holiday wrote. “I didn’t want to start anything I couldn’t finish. But one night after everybody had asked me twenty times to do it, I finally gave in.”

The audience applauded so long that they were still applauding after she left the stage and changed into her street clothes.

“Not many other singers ever tried to do ‘Strange Fruit.’ I never tried to discourage them,” Holiday wrote, “but audiences did.”

When she came to the song’s last phrase that night, Holiday recalled, “I was in the angriest and strongest voice I had been in for months. My piano player was in the same kind of form. When I said, ‘… for the sun to rot,’ and then a piano punctuation, ‘… for the wind to suck,’ I pounced on those words like they had never been hit before.”

THE LEGACY OF ‘STRANGE FRUIT’

Diana Ross sang “Strange Fruit” during the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony of March 2000 as Ross inducted the late Billie Holiday into the “Early Influence” category, according to The Diana Ross Project. Ross starred in Lady Sings the Blues in 1972, a film about Holiday’s life.

West’s performance of the track at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards drove home the power of the song. On a completely dark stage, the notes of Simone singing “Strange Fruit” blares while West recites his rap. As the song intensifies, Steve McQueen’s photograph “Lynching Tree” is illuminated behind West, creating a silhouette effect for the performance.

“‘Strange Fruit’ carries so much political weight, and ‘Blood on the Leaves’ is more about past relationships, but you can draw some parallels between the two,” said one of the six producers on the track, Hudson Mohawke in a 2013 interview with Pitchfork.

The song continues to impact yet another generation, with Kanye West’s 2013 rap release “Blood on the Leaves” featuring a sample of Nina Simone’s 1965 cover of “Strange Fruit.”

CONTROVERSY AROUND ‘STRANGE FRUIT’

Not every performance of “Strange Fruit” received positive reviews the way West’s did. Blond-haired and blue-eyed singer Annie Lennox was criticized after she covered “Strange Fruit” for her 2014 album and failed to mention lynching in any of the press work she did for the album. She acknowledged that it stood for racism, but chose rather to focus on the song as an anthem for “female empowerment.”

In an interview with PBS, Lennox stated: “If she [Holiday] was here now, we would have a lot in common. There would be a lot of things that we could talk about … like female empowerment, women’s rights, bigotry, racism. … We could talk about lipstick, too.”

TIME MAGAZINE NAMES ‘STRANGE FRUIT’ SONG OF THE CENTURY

Sixty years after Billie Holiday first sang “Strange Fruit” and 60 years after the magazine had first called the song “musical propaganda,” Time named it the Song of the Century on the last day of 1999. The magazine offered one line of explanation: “In this sad, shadowy song about lynching in the South, history’s greatest jazz singer comes to terms with history itself.”

Three years later, in 2002, the Library of Congress added the song to its inaugural class of the National Recording Registry, a list dedicated to preserving American sound heritage.

“Though the artistry of the song was always there, obviously the advent of the Civil Rights movement and the need to bring greater attention to various aspects of America’s sometimes bleak, unfortunate past has only elevated the popularity and need for the song to be heard and remembered,” Cary O’Dell wrote in an email. O’Dell is the boards assistant to the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress.

“That this song was recorded in 1939, yet remains (sadly) applicable in many ways is another remarkable achievement of ‘Strange Fruit,’” O’Dell continued.

HOLIDAY’S LEGACY PREVAILS

During a performance in 1959, Holiday takes 3 minutes, 18 seconds to sing a song that’s 13 lines long. As the last bars of “Strange Fruit” play from the keys of the piano at the Café Society, Holiday pauses between each line for emphasis. With a powerful crescendo from the slow piano-laden tune to one final belting, halting note, a band emerges to triumphantly close Holiday’s set. Holiday grabs her audience’s attention and does not let go.

As the music ceases, Holiday does not bow. She does not smile. She does not wave. The stage is filled with an eerie silence.

“Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck./ For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck./ For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop./ Here is a strange and bitter crooooooooooooooop.”