By Gabriel Pietrorazio

Not quite 40 years after Freedom of the Press became protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution, a group of free Black men came together to discuss the news of the day and the newspapers that delivered it.

Before that, newspapers were owned, operated and staffed by white people, and they consistently ignored most of the interests, celebrations and anxieties of the local Black communities.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

So they declared journalistic independence and launched a publication by, for and about people who looked like them. They decided to call it Freedom’s Journal, and with that, the Black press in America was born.

The March 16, 1827, front page of Freedom’s Journal proclaimed that the newspaper’s mission:

“Too long have others spoken for us. Too long has the publick been deceived by misrepresentation in things which concern us dearly; though in the estimation of some mere trifles; for though there are many in society who exercise towards us benevolent feelings; still (with sorrow we confess it) there are others who make it their business to enlarge upon the least trifle, which tends to the discredit of any person of colour; and pronounce anathemas and denounce our whole body for the misconduct of this guilty one.”

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

“We are aware that there many instances of vice among us, but we avow it is because no one has taught its subjects to be virtuous; many instances of poverty because no sufficient efforts accommodated to minds contracted by slavery, and deprived of early education have been made, to teach them how to husband their hard earnings, and to secure to themselves comforts.”

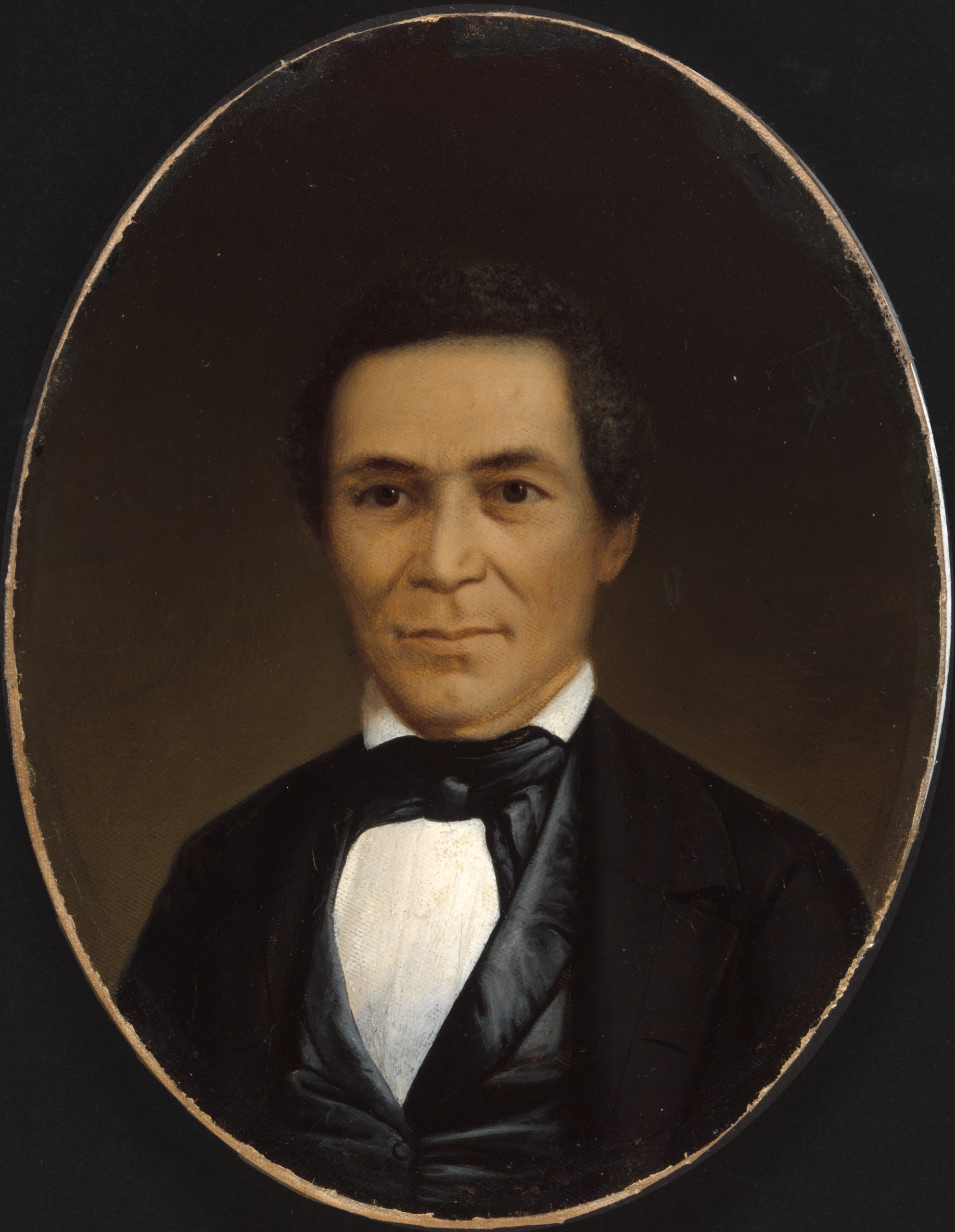

Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm were listed as the editors and publishers of Freedom’s Journal, and each represented a different strain of the anti-slavery movement of their time.

Cornish had been born free in the North and leaned toward the abolitionist strain of the movement, which considered slavery a moral wrong and advocated for ending its practice, emancipating the slaves and their free life.

Russwurm had been born to an enslaved Black woman in Jamaica. He leaned toward those in the movement who favored emigration to Haiti, where a free, Black-run republic had existed since 1804, and later to Liberia, where a colony of formerly enslaved Africans from the United States and the Caribbean were being urged to settle for a better life.

Cornish left the newspaper later that same year in 1827, and in 1829, Russwurm moved to Liberia. Freedom’s Journal as its readers and supporters had come to know it was over. Yet, by the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, the Black press nationwide could count more than three dozen publications in its ranks.

And the next major development affecting the development of that press was seeded in the very divisions that had separated Cornish and Russwurm.

In 1862, President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, which paid slaveowners up to $300 for every person set free, about $8,000 each in current US dollars.

“That’s right, slaveowners got reparations,” Tera W. Hunter, a professor of African-American Studies at Princeton University, wrote in The New York Times. “Enslaved African-Americans got nothing for their generations of stolen bodies, snatched children and expropriated labor other than their mere release from legal bondage.”

While “the formerly enslaved received nothing if they decided to stay in the United States,” University of Connecticut public policy professor Thomas Craemer wrote, it “provided for an emigration incentive of $100—around $2,683 in 2021 dollars—if the formerly enslaved agreed to permanently leave the United States.” Russwurm stood in support of this approach for actualizing freedom.

Abolitionists leaned toward Cornish’s thinking, and the Senate seemed to do so, as well. In 1863, unable to get satisfactory congressional action, Lincoln issued an executive order: the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all enslaved persons in Confederate-controlled areas. No financial strings were attached.

From that point on, the readership and circulation base of the Black press could grow and it would, accelerated by the Great Migration that took the formerly enslaved families whose work had been the foundation of the agricultural economy of the South to the better jobs and better lives in the industrial North.

Between the launch of Freedom’s Journal and the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Black press would remain true not only to the crusade for justice, but also to Cornish and Russwurm’s admonition to tell stories not told by white-owned media in the words and voices of those whose stories they are.

Those newspapers were “taking up the mantle of Freedom’s Journal,” Christoph Mergerson, a visiting assistant professor in race and media at the University of Maryland, told the Howard Center:

“When you take into consideration the extent to which the needs of Black Americans, the concerns of Black Americans were neglected throughout the predominant American press, it’s no small thing to set… that expectation that that’s how the press should be serving you if you’re Black American, because those are many of the same ways that they were serving white Americans, but nobody thought of our needs.”