By Anuoluwapo Adefiwitan

George White prayed incessantly as the lynch mob leaders placed dry straw around him and a stake with twigs in Wilmington, Delaware.

While beseeching God in the early hours of June 23, 1903, he heard the footsteps of the growing thousands who surrounded him to watch his death.

As the pyre was fully prepared near Price’s Corner, the location of his alleged crime, a mob leader wrapped White in “strong” rope “from his shoulders to his feet,” and dragged him closer to the stake, according to stories in Wilmington newspapers.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

White muttered his final cry, “God, help me!” as the mob leader set fire to the straw. As the flame burned off his clothes and the rope, he tried to escape. “Willing hands,” the newspapers reported, repeatedly returned White to his stake.

While White’s body lay still, ablaze and reeking of burnt flesh, a “young and pretty woman” was brought near the stake. “She was pale but appeared to be satisfied that proper justice was being meted out to the man,” The News Journal of Wilmington, Delaware,. reported.

“SHOULD THE MURDERER OF MISS BISHOP BE LYNCHED?”

White’s lynching was incited by two major forces of the post-Civil War South: the church and the press, specifically The News Journal, Evening Journal and The Morning News of Delaware.

White, a Black farm laborer, was apprehended on June 16, 1903, accused of fatally assaulting Helen S. Bishop, daughter of a local minister and school superintendent, on the previous day.

His trial date was set for September, which caused anger among community members who thought White should “enjoy his right to a speedy and public trial,” according to The Morning News.

Within days of White’s arrest, Bishop died from her injuries and anger grew. The News Journal told readers where White was being held until trial. The Evening Journal also implied that the growing unrest in the town might result in Delaware’s second lynching: “Hundreds viewed the remains of the unfortunate girl, and from the remarks heard, the fate of George White … would have been most quickly settled had he been on the grounds,’’ the paper reported.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

On June 20, 1903, the Evening Journal ran an ad for a sermon the Rev. Robert A. Elwood planned for the next day, “Should the Murderer of Miss Bishop be Lynched?” An unsuccessful attempt to lynch White was organized on the night the ad appeared.

On June 21, Elwood stood before the 2,500 people filling the pews of his church, Olivet Presbyterian, in Wilmington, Delaware.

He began, “I have chosen to speak to you tonight from two texts, one found in the Bible, First Corinthians 5:13, ‘Therefore put away from among yourselves that wicked person.’ And the other in that document … the greatest ever written next to the Bible, the Constitution of the United States, and of it the Sixth Amendment, reading thus: ‘In all criminal case prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial.’ ”

Elwood said that by not honoring God and the Constitution and putting White on trial quickly, the responsibility would fall on the judges who delayed the trial if White were lynched. “Who did this?’’ Elwood preached. “Was it a wild beast loose from its captors and found an easy prey? … Was it an imp of hell, taking vengeance on a defenseless human? No, but it was a man with the heart of a beast, with the desires of a fiend who gave vent to his bestiality and executed this damnable crime.”

The impassioned minister showed leaves that he said were stained with the blood of Bishop.

The Evening Journal reported the quotes from Elwood’s sermon the next day.

White Christianity in former slave states like Delaware was “one of the most insidious ways to maintain white supremacy and white privilege,’’ said historian and author C.R. Gibbs.

“The stage was set inside the churches through countless sermons questioning the humanity of Black people,’’ Gibbs said. “When you had the supposed best levels of Southern society heavily involved in the same kind of rhetoric, then the discord itself became more approving of violence.

“When you have religion against a people, when you have the law against a people, then there is no hope for immediate mitigation of the conditions under which they are held.”

The mob dragged White from the jail and burned him alive less than 48 hours after Elwood’s sermon.

Some white preachers denounced White’s lynching. Yet their counter-sermons also promoted racist attitudes towards African Americans in the name of Christ and the Constitution.

The Rev. A.N. Keigwin, pastor of the West Presbyterian church in Delaware, condemned the lynching and said citizens should be “thanking God we have grace enough to be indignant at such crimes, and grace enough to be ashamed of ourselves.”

Yet, he preached, the cruelty done to White was “as natural an outbreak of human feeling as any act of human nature. … It was an outburst of passion as natural as breathing.”

If there were an exceptional case in which to take out vengeance, Keigwin said from the pulpit, the lynching of White would “head the list.” He went on to say: “I cannot speak temperately of the worse than brute who perpetrated the outrage. I cannot allow myself to think of the horror, the unspeakable suffering of that innocent young woman in the power of the arch fiend.”

Both Keigwin and Elwood preached on natural versus man-made law. Elwood said, “Law is the order of the universe” and “was not first made by man.”Keigwin said, “The order of nature is law, the order of society is law.”

Both Elwood and Keigwin encouraged their congregants to elect those who would favor speedy trials for everyone, especially those who are presumed guilty.

WHITE SUPREMACY PERVADING THE PRESS

Keigwin was commended in the press for having “been calm and temperate in utterances” in his sermon.

Although all three newspapers published content that showed disapproval of White’s lynching, the coverage reflected the influence of the culture of a slave state where the mindset of God-ordained white supremacy reigned, including in the press.

David R. Davies, a professor of journalism at the University of Southern Mississippi, said, “White supremacy was a given’’ in newspapers. “These viewpoints were stated just outright that one race is superior and one race is inferior.”

The Evening Journal advertised the title of Elwood’s sermon and reported the most provocative and derogatory parts. Additionally, it labeled White as “a negro of bad repute” when reporting his arrest, noting that the knife marks on the neck of White’s alleged victim were “simple and impressive.”

The Evening Journal reported on the response of a local Black pastor to White’s death, calling the sermon by the Rev. Montrose W. Thornton, pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, “sensational” and “inflammatory.”

The paper said Thornton’s sermon “aroused the negroes,” citing as “inflammatory” the minister’s assertion that “the negro race is no better or worse than the Caucasian or any other.”

In that same edition, the Journal ran Keigwin’s sermon and published a story from the Middletown Transcript that called Elwood’s sermon “sensational.”

A day after White was lynched, The Morning News published a photo of him with the caption, “Murderer, George White,” even though he had never been tried, much less convicted.

The News Journal’s reporter, in the story “The Negro Burned At The Stake,” claimed White had confessed and provided readers with a word-for-word version despite the lack of evidence that such a confession existed.

LYNCHINGS IN DELAWARE

White’s murder is the only Delaware lynching recorded with the Equal Justice Initiative. But the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found at least one more victim. Before the Civil War, Joe Hamilton was lynched in Smyrna. And historians are searching for evidence of others.

In 1922, poet and civil rights activist Alice Dunbar-Nelson, along with some members of the African American community in Dover, urged U.S. Rep. Caleb R. Layton to support a federal anti-lynching bill sponsored by fellow Republican Rep. Leonidas Dyer of Missouri.

Layton declined. “If the bill were to become a law and a lynching took place in Delaware, the county in which it occurred would be taxed $10,000,’’ he said. “The public, innocent of any connection with the crime committed, would have to pay the survivors of the dead man that sum. … Levying of such a tax upon the county or the people of the county is contrary to the Constitution, which says that no taxes except general one shall be admissible.”

Layton, a physician, did state that “the purposes of the bill are good.” It passed the House but was killed in the Senate by Southern Democrats.

Dunbar-Nelson, wife of Black poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar, describes Delaware in her 1924 article, “A Jewel of Inconsistencies,” as “a state of anomalies, of political and social contradictions.”

These anomalies included the white community’s response to White’s murder. Although she states that many whites did not agree with his lynching, many whites joined Elwood’s church after his sermon and the congregation published an article defending his words and saying his sermon was not responsible for White’s lynching.

Elwood was eventually called before the New Castle Presbytery for preaching “contrary to the Christian faith,” but faced no repercussions. According to the Journal of Presbyterian History, Elwood eventually left Wilmington for another pastor position in Leavenworth, Kansas.

NAACP leader Walter White wrote in 1929 that “it is exceedingly doubtful if lynching could possibly exist under any other religion than Christianity. … Through tacit approval and acquiescence has the Christian Church indirectly given its approval to lynch law and other forms of race prejudice.”

GEORGE WHITE REMEMBERED

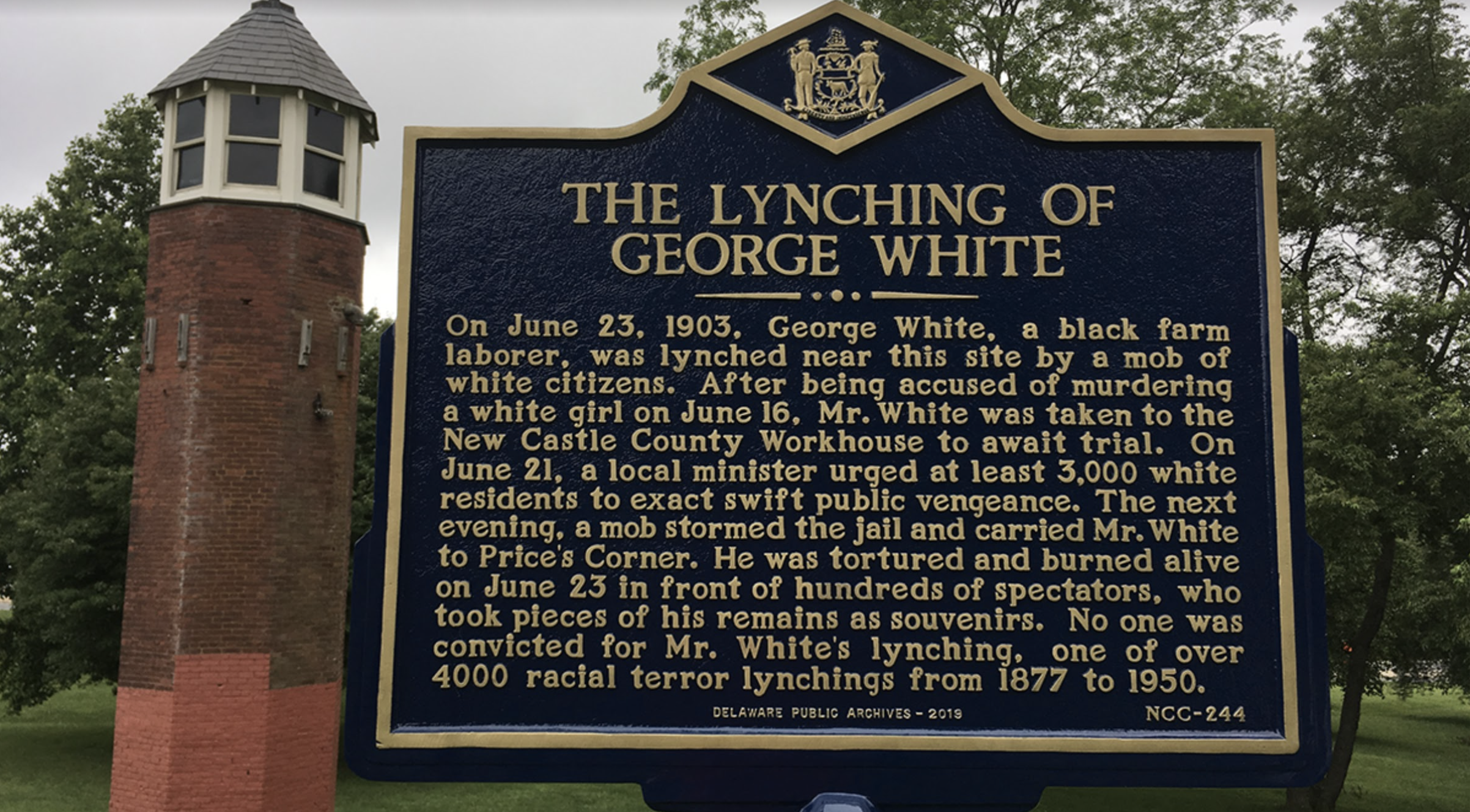

Delaware Online, the present iteration of The News Journal, reported the unveiling of a historical marker dedicated to George White in June 2019. By August, the marker had been stolen. It was replaced two months later in October.