Newspapers dehumanized Black victims of lynchings in Tallahassee by describing them as animals or insane

By Torrence Banks

Tallahassee, Fla. – Members of the Tallahassee Community Remembrance Project waited under the roof of a gray building where the Leon County Jail once stood, seeing if the rain would pass. They were among about 400 people who gathered in Cascades Park on July 17 to commemorate the deaths of four Black men who were taken from the Leon County Jail and lynched between 1897 and 1937. The area where the jail once stood is now occupied by a hotel, restaurants and apartments.

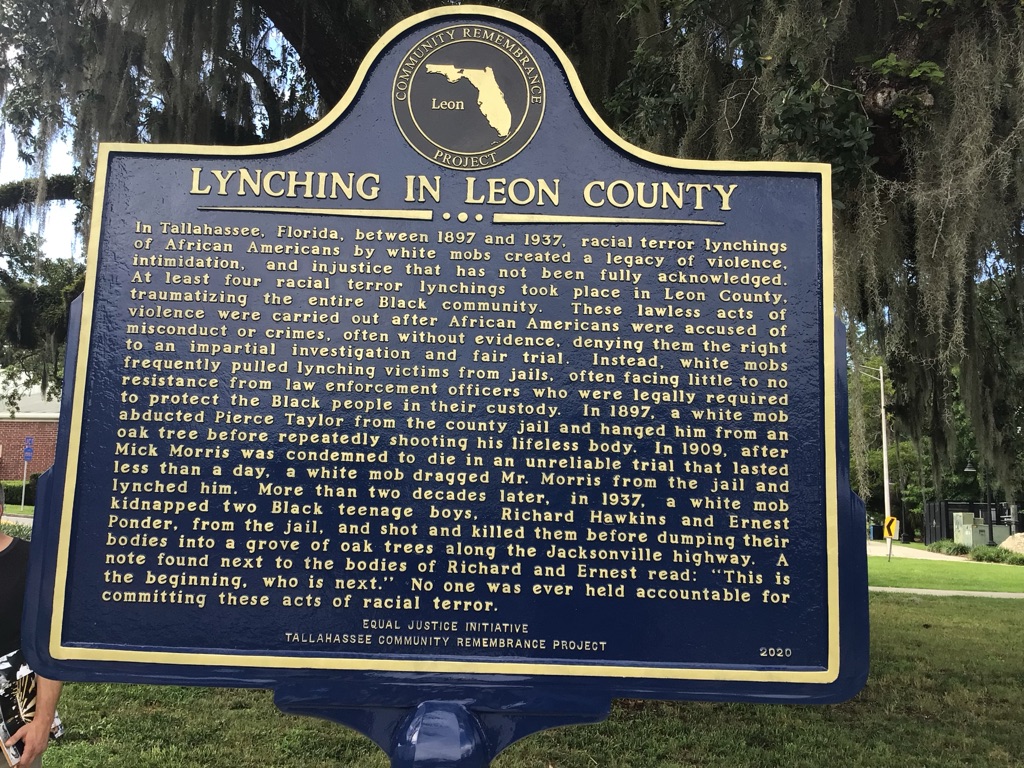

The organizers moved the ceremony to the ballroom of the nearby AC Hotel by Marriott until the rain cleared, then returned outside for the unveiling of a historical marker. Once the black veil was lifted, the crowd burst into applause. The words “Lynching in Leon County” were written in bold, acknowledging a long-concealed past, lending hope that racial terror can be prevented in the future.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

One of the names on the marker is Mick Morris. The Florida turpentine worker was taken from the jail at 3 a.m. on June 6, 1909, by a mob of 15 masked men. Morris was clubbed, hung on a tree and shot multiple times after he was already dead, according to an account in William Wilbanks’ book, “Forgotten Heroes: Police Officers Killed in Early Florida, 1840-1925.” Morris was convicted of killing the county sheriff and sentenced to be executed by the state, but the mob acted first.

News coverage of his death, including from The Associated Press, used such descriptions as Morris “fought like a tiger” and reported rumors that he had gone “insane.” Historians said white-owned newspapers used such language in numerous lynching cases to justify the deaths of Black victims to white readers.

Wilbanks’ book tells the story of the events that led to Morris’ lynching, citing multiple white newspapers. According to the book, Willie M. Langston, the sheriff of Leon County, traveled to near Spring Hill, Georgia, to serve Morris a warrant for “stealing a keg.” While searching for Morris in a dark house, Langston was shot and killed.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

Morris fled to near Thomasville, Georgia, to stay at his father-in-law’s home, before being arrested on March 30, 1909, and taken back to Florida by Langston’s replacement, Sheriff J.P.S. Houston. Morris later said the shooting was an accident.

Hoping to avoid the death penalty, Morris pleaded guilty to the shooting and collapsed when he received his severe sentence, according to The Weekly True Democrat.

After the one-hour trial, he was taken to Leon County Jail. While there, rumors began circulating in the community questioning Morris’ sanity. In the June 8, 1909, issue of the Gainesville Daily Sun, an article titled “NEGRO IS LYNCHED AT THE STATE CAPITAL” said, “A rumor which was about town Saturday was to the effect that the negro had gone insane.” The article went on to state that “the mob secretly organized,” thinking Morris’ scheme “might result in cheating the gallows.”

“I don’t know of a single case during that period where anybody got off by claiming to be insane,” said Marvin Dunn, a historian and author of “The Beast in Florida: A History of Anti-Black Violence.” “That would have been unique if he had been able to claim that and gotten off. That’s ridiculous. So it sounds to me like a cover story for the mob to have done what they did.”

Corrie Claiborne, an associate professor of English at Morehouse College who has lectured and written on literature and Black culture, said such language was an attempt to excuse actions. “So you can literally take this one ‘crazy Negro,’ and use that as an excuse to, you know, burn down all the churches and schools and houses in the neighborhood, kill other people because you will say, ‘Oh, I saw this Black man walking down the street. He could have been crazy like that other Negro,’” she said.

Language published in June 1909 issues of The Enterprise-Recorder, Gainesville Daily Sun and The Pensacola Journal said Morris “fought like a tiger from the moment his cell was entered.” Historians and academics said white newspapers used such animalistic language to create fear of Black people among white citizens and to demonstrate their control over Black people.

“White newspapers during this period are one of the main proponents of the idea of innate Black criminality,” said Tameka Bradley Hobbs, associate provost of academic affairs and a history professor at Florida Memorial University. “It was almost taken for granted, generally, that African Americans were less intelligent, less capable.

“I think that is definitely a common element to enhance the fear and the danger of Black people, especially Black men,” she added. “They’re compared to animals, they’re described as extremely dangerous and violent, uncontrollable and threatening. And it as a counterbalance justifies the really extreme type of torture that many of those lynching victims … experienced.”

The Tallahassee Community Remembrance Project has not found any accounts from Morris or anyone discussing what was going on with his mental health; only rumors. Sandra Howard, a partner with the project, said, “I don’t think there’s any real understanding about what was actually going on with him. There was not, that I understand it, a chance for him to really talk about the circumstances involving the case nor his own mental health.”

Several Florida newspapers, including The Pensacola Journal and the Gainesville Daily Sun, published an Associated Press story on Morris’ lynching that used the phrase “fought like a tiger.” Lauren Easton, global director of media relations and corporate communications for AP, wrote in a statement that there is not any definitive way to know if the phrase was created by AP or if another correspondent wrote it and then sent it to AP.

“Previous research has indicated lynching was often treated as a local event, covered by local correspondents, at times with contributions from AP, which may explain why Florida papers covered the Morris lynching in Tallahassee so thoroughly,” Easton wrote.

Easton described AP as “a news agency that provides news to a vast array of media outlets,” and not a newspaper that “advocates on public issues.”

“We know of no instance in which the AP deliberately promoted racist violence,” Easton wrote. “However, the AP reported on lynching and other forms of racial violence over many years, sometimes in disturbing detail, with flaws and omissions. These shortcomings clearly reflected the attitudes and prejudices of the era in which these reports were written. But that is no excuse, and we regret them.”

The Feb. 26, 1909, issue of The Florida Star contained another prejudicial portrayal of African Americans. A letter titled “An Appeal” referred to Will McFadden, who was accused of rape, as a “negro rapist fiend.” It also praised Sheriff J.P. Brown, saying the officer’s arrest of McFadden protected wives and children.

A June 8, 1894, issue of South Carolina’s The Weekly Ledger described the lynching of Hardy Gill, a Black man who was accused of brutally attacking a woman and her baby. The headline read, “AN INSANE NEGRO LYNCHED,” and the story said Gill was declared insane by a judge before his trial. The next day, several men took Gill from his cell and left him in the road dead with several bullet wounds.

According to Jack E. Davis, a history professor at the University of Florida, some white Florida newspapers during the era condemned the actions of lynch mobs because they were concerned about the negative perception of their state. The June 8, 1909, issue of The Tampa Morning Tribune, for instance, called the lynching of Morris despicable, unjustifiable and cowardly. It also said the act “brought disgrace upon the good name of Florida,” created “distorted views of the South” and humiliated Southern citizens.

Dunn said Black newspapers often voiced African Americans’ frustrations and concerns about lynchings. The June 12, 1909, issue of The Richmond Planet mentioned Morris was behaving strangely and the members of the mob were prompted to act because they feared he was pretending to be insane to escape his execution.

The headline read, “A LYNCHING IN FLORIDA.” The story, which referred to Mick Morris as “Maik Morris,” questioned why Black people who are accused of committing a crime should surrender to law enforcement when their protection in jail cannot be guaranteed.

“It seems to us that the proper way to check this species of lawlessness is to meet the lynchers and murderers face to face and die fighting with a gun in our hands,” The Richmond Planet article read.

While The Richmond Planet spoke out against Morris’ lynching, The Advocate, a Black newspaper in West Virginia, published an account similar to those in white newspapers. Its headline in the June 10, 1909, issue read “MAD NEGRO” in bold letters. However, The Advocate’s account is different in that it does not mention the phrase “fought like a tiger” when describing Morris’ struggle.

News Coverage Today

Hobbs said media coverage of African American victims today is not as egregious as in the 1900s, but she believes it is similar. Other researchers and journalists see parallels, and cite coverage by conservative media outlets of the murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin.

Chelsea Fuller, media-related representative on the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) Board of Directors and vice president of communications at Time’s Up, said, “The defense and right-wing media really tried to hammer down on the fact that (George Floyd) had had previous encounters with the police, that he was a drug addict.

“It’s like, we watched. We watched a man lean on the neck of another human being until he lost the ability to breathe. … There are media companies across this country who have pushed back against that.”

Douglas Ray, executive editor and market leader at The Gainesville Sun, said the news outlet is working with local historians and researchers on a project that will examine how the newspaper covered race and lynchings during the Jim Crow period, which lasted from 1877 to 1954. (The paper dropped “Daily” from its name in 1963.)

“I think it’s also important that we do this in a way that is as transparent and open as possible,” Ray said. “Just having internal staff do this work without engagement with the broader community didn’t seem to me like the best approach.”

He said The Gainesville Sun plans to continue to seek diverse voices in the Black community. To ensure that the coverage of the Black community is not monolithic, Ray said more Black journalists are needed in newsrooms and community outreach is necessary to tell authentic stories.

About six years ago, The Sun started a Gainesville For All initiative after a Black teenager was shot several times by police. “It’s now a standalone agency,” Ray said. “But when we started that, it was The Gainesville Sun’s effort to try to engage the broader community in looking at racial disparities and what causes them and how we can resolve them.”

Today, the Pensacola News Journal also has been more conscious of the image of African Americans presented by the news outlet. The Gannett-owned newspaper, along with others in the company, has stopped running arrest logs.

“When we run arrest logs, we help perpetuate that narrative that, you know, Black people are doing more crime, and they’re not,” Executive Editor Lisa Nellessen Savage said.

“We’ve got to be there for all the good stories as well as the bad. We can’t write about crime in a community if we’re not, on a daily basis, writing about the new businesses, the academic achievements.”

‘Strange Fruit’

Today, the Tallahassee site where four men were taken from the Leon County Jail and lynched is owned by North American Properties. It was one of three historical buildings that occupied the current Cascades Park property. Of the other two buildings, the Leon Health Unit and the former Works Projects Administration (WPA) District Offices, only the Health Unit remains up today.

The jail was torn down in 2018. However, North American Properties plans to incorporate a huge public plaza that will recognize the history of the property.

Before the historic marker was unveiled in July, social-justice activists from the Equal Justice Initiative delivered remarks inside the ballroom. Takeshia Stokes sang Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” After the song, Tallahassee City Commissioner Dianne Williams-Cox came up to the podium to share her memory of the song and the importance of remembering the four men whose names were on the historical marker: Pierce Taylor, Mick Morris, Ernest Ponder and Richard Hawkins.

“As I sat here and listened to the singing of ‘Strange Fruit,’ I’m remembering how once upon a time, it was illegal to sing that song in the South,” Williams-Cox said.

“We must remember. There’s not much we can do for the four gentlemen who lost their lives, and many others. Don’t be mistaken, there were more than four. There were more than four. And one day, someone will document the others.”