By Nhaya Vaidya & Sara Wiatrak

A lesson once taught in the Pioneer’s school, That this is a land of WHITE MAN’S RULE.

The Red Man once in an early day, Was told by the Whites to mend his way.

The negro, now, by eternal grace, Must learn to stay in the negro’s place.

In the Sunny South, the Land of the Free, Let the WHITE SUPREME forever be.

Let this a warning to all negroes be, Or they’ll suffer the fate of the DOGWOOD TREE.

Published by Harkrider Drug Co., Center, Texas.

Unknown Copyright

Note to readers: This story contains graphic and disturbing images.

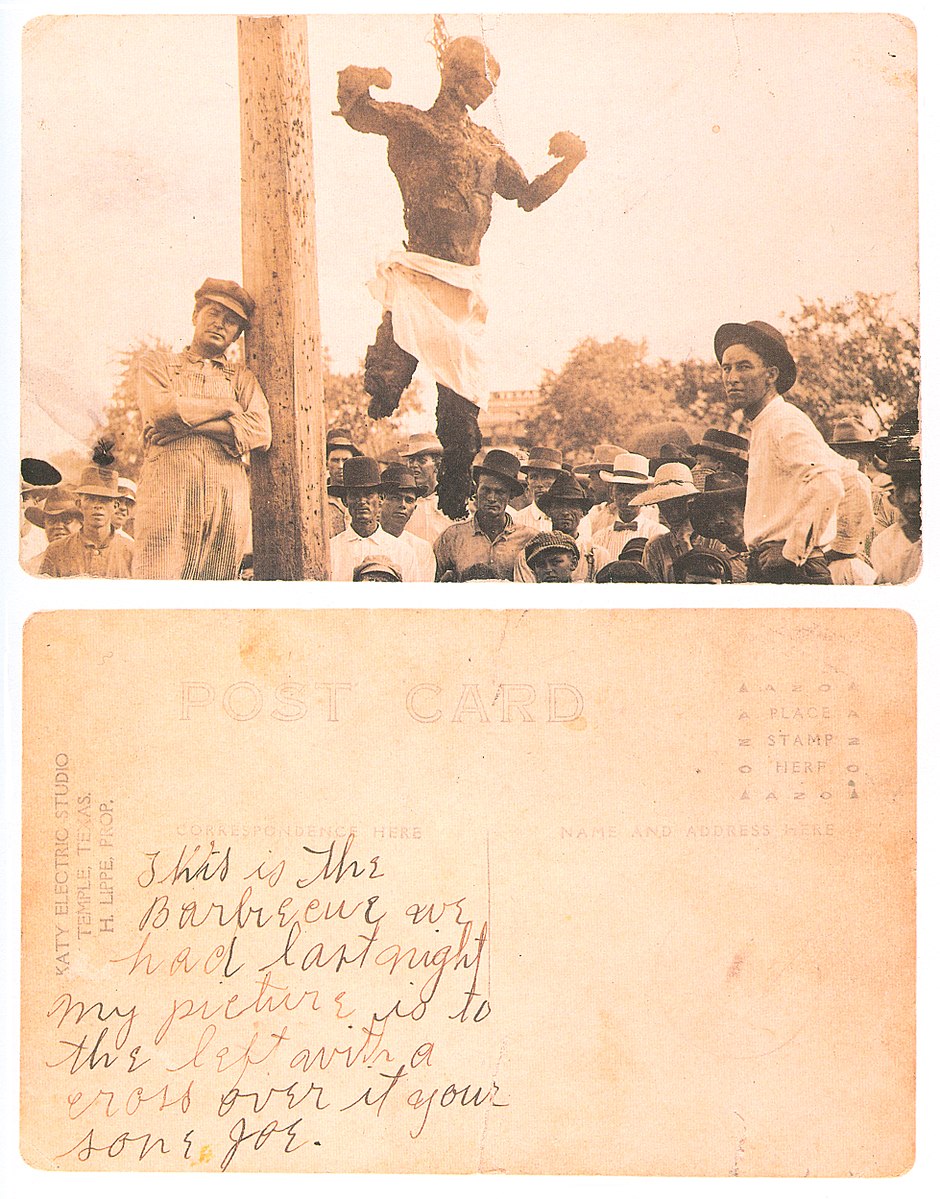

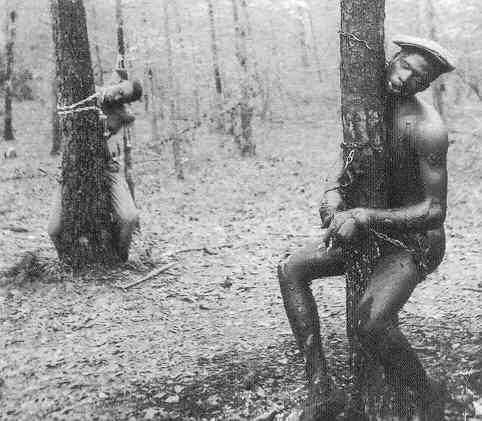

During the late 19th and early 20th century, thousands of photographs and postcards of Black Americans killed by white mobs in racist terror lynchings were collected, traded and sent through the U.S. postal service.

The postcards and photographs, depicting gruesome images of the bodies of Black men, women and children who had been tied to trees, mutilated, tortured, shot and burned alive by white mobs, were often distributed as souvenirs and saved as mementos in family albums and stored away in attics for safekeeping.

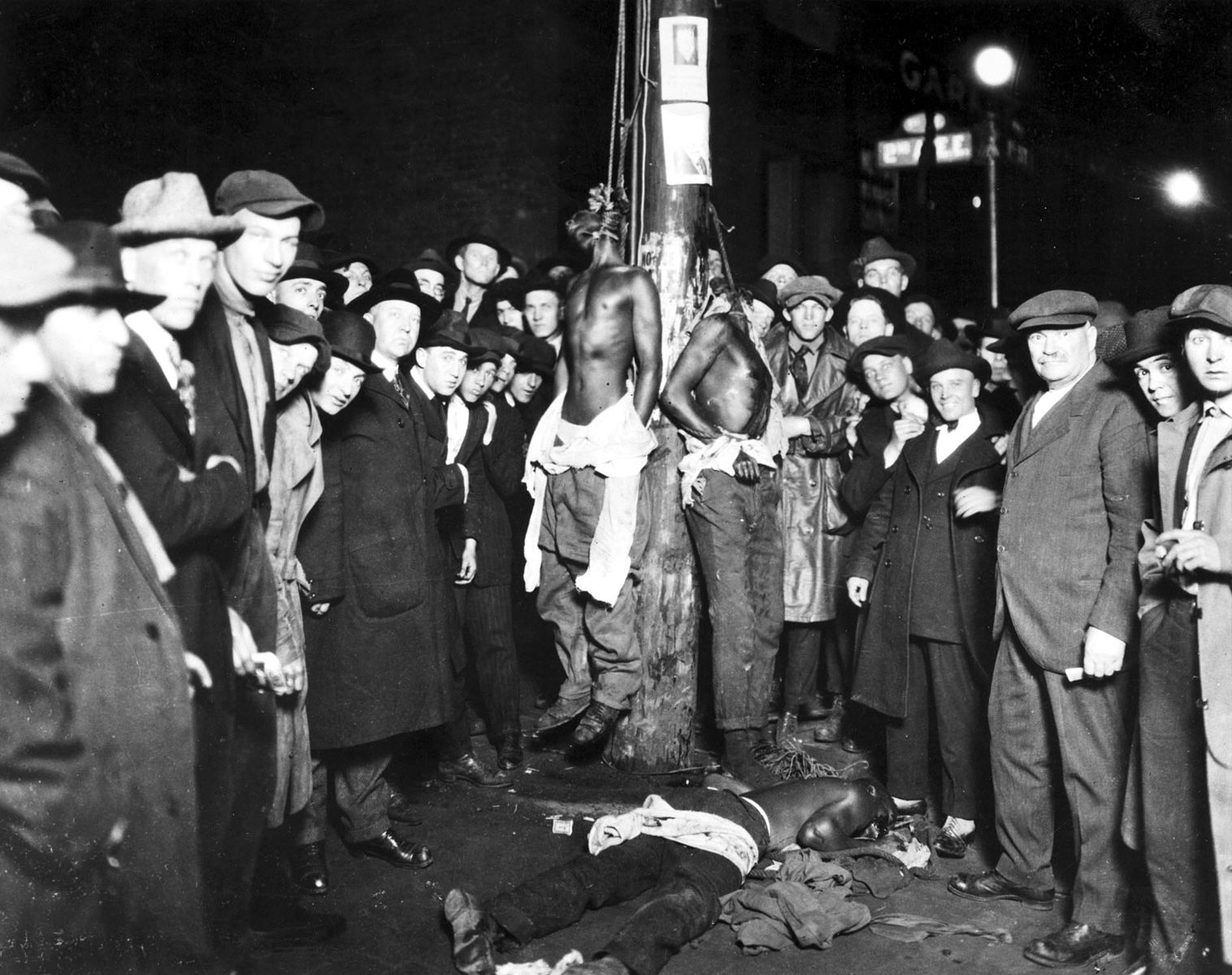

The lynching photographs often captured the bodies of the murdered Black Americans and the hundreds of white people — including children — who gathered to witness the public spectacle of lynchings. According to historians, in more than half of these photos and postcards, white people were shown smiling and celebrating the spectacles.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

“These photographs represent what happens when we refuse to see each other’s humanity,” said David Fakunle, CEO of DiscoverME/RecoverME: Enrichment Through the African Oral Tradition, in an interview with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism. “You can only do this because you never see this person as a person in the first place. The same photos that are meant to be kept as a fond memory are being used to show horror. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, horror in the eye of the beholder.”

Although the images of racist terror lynchings were widely distributed within white communities across the country, the Howard Center found that these lynching photos were rarely published in white-owned newspapers, even those that incited racist terror and lynchings.

White-owned newspapers were careful not to sensationalize lynching photos, said Amy Louise Wood, author of “Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940.”

“The community gets to see the criminal be executed,” Wood said. “That would have been part of their culture. They wouldn’t have been disgusted by that. They would have seen it as a right.”

If photos of lynchings were published in white newspapers, they were typically inserted toward the middle of the issue and were sized to be small, only taking up a quarter of the page or less, Wood said.

In her book, Wood argued that many white Southerners did not want national attention drawn to images of lynchings that depicted their racist violence. “For one, lynching photographs rarely appeared in the mainstream press or in southern newspapers before the 1930s,” wrote Wood, “and then only under exceptional circumstances, even though large, urban newspapers had the technology to do so beginning in the 1890s.”

A reporter working for a Memphis newspaper in 1892 reported, Wood explained, “that he had been given a photograph from a recent lynching in Mississippi only under the ‘express pledge’ that he neither publish the image or identify the men in the picture. Although this reporter deemed the lynching legitimate under ‘unwritten law’ because of the ghastliness of the black man’s alleged crime, he still ‘thought [it] best to preserve the secrecy of the transaction.’”

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

Wood wrote that the white reporter’s explanation was historically noteworthy “because the reporter expressed astonishment that the men had the ‘audacious design’ to photograph themselves with the lynched body of their victim and remarked on the ‘novelty’ of the image, which ‘fairly outdoes anything ever recorded in the annals of photography.’”

Smaller white-owned newspapers did not often publish lynching photographs because they did not have the means to print photographs until the 1920s, Wood said in an interview. Larger, mainstream white-owned newspapers often decided not to publish lynching photographs because they wanted to protect the identities of the white mob attending lynchings and to protect the reputation of the South as genteel.

In 1895, The Atlanta Constitution wrote an editorial criticizing The (New York) World for publishing a photograph of the lynching of Robert Hilliard in Tyler, Texas. “The Atlanta Constitution further expressed concern that such images only fueled the national perception that ‘the South was a land of barbarians,’” Wood wrote. “To publish the lynching photograph was, in this sense, a form of ‘pictorial libeling’ against the good people of the South.”

Wood said in an interview that Southern communities preferred to circulate the images of lynchings within their own communities by exchanging lynching postcards. Communities were concerned about photos and postcards getting out, not wanting them to be used in anti-lynching campaigns, Wood said.

“They made a real effort to keep the photos in their community,” Wood said. Instead of printing the images on the front pages, “they made them into postcards.”

A TRIPLE LYNCHING IN 1920

On June 15, 1920, three Black men working for the John Robinson Circus were dragged from a jail in Duluth, Minnesota, and lynched. The men — identified as Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie — were falsely accused, along with three of their colleagues, of assaulting a 17-year-old white girl.

“Immediate investigation will be made by county authorities into the lynching of 3 negroes here last night by a mob of 5,000 persons, which battered their way into the police station to secure the negroes,” according to a June 17, 1920, article in the The Fort Scott Tribune newspaper.”

“Last night’s lynchings,” the Tribune reported, “were accomplished after the city’s fire hose had been used in an attack on police headquarters, which fronts Superior street, Duluth’s principal business thoroughfare. For at least two hours, the mob ruled, only relinquishing its power after the negroes had been lynched.”

The triple lynching was widely covered in local and national newspapers. According to the Minnesota Historical Society, The Ely Miner newspaper did not express regret for the lynching. Instead, the newspaper claimed that “while the thing was wrong in principle, it was most effective and those who were put out of their criminal existence by the mob will not assault any more young girls.”

The Mankato Daily Free Press called the Black men “beasts in human shape,” and said the lynching was more appropriate than a trial.

“Mad dogs are shot dead without ceremony. Beasts in human shape are entitled to but scant consideration. The law gives them by far too much of an advantage,” the paper reported.

The Duluth Herald didn’t print photos of the lynching victims. Instead, the newspaper published a photo depicting the aftermath of the mob violence at the city’s police headquarters, from which the mob pulled the three men.

The headline “‘Duluth Mob Lynches Three Negroes,’ ran in papers from the Duluth News-Tribune to the New York Times,” according to MPR News.

The photo of the three Black men was turned into postcards and widely circulated. The postcards show that the body of Clayton had been cut down in order to get a better picture for photographer Ralph Greenspun. The prints were then sold as souvenir postcards in Duluth stores.

The images of the Duluth triple lynching became iconic, freezing the racist terror violence in time and place. “The photographs provided seemingly indisputable graphic testimony to white southerners’s feelings of racial superiority,” Wood wrote. “In a lynching, the perpetrators, through their torture, took the black man’s body apart piece by piece to obliterate his human and masculine identity, to make him into the ‘black beast’ that their racial and sexual ideology purported him to be.’”

White-owned newspapers perpetuated these myths by printing gross racial stereotypes and images of Black Americans, said Margaret Vandiver, member and researcher at The Lynching Sites Project of Memphis, a network of community members examining the history of racial violence in Shelby County, Tennessee..

“When a Black person was a victim of crime, there was a mockery of them,” Vandiver said. “There was no pretense of fairness in the white newspaper.”

Vandiver said that the purpose of lynchings was to present and maintain the entrenched fallacy of white supremacy across social boundaries.

“It is important to reflect on the dehumanizing of African American men that opens the door to lynchings,” Vandiver said, explaining that she believes the history of lynchings does not disappear with time. “The only way to get beyond it is to understand as much as we can.”

LYNCHINGS AS ‘PUBLIC SPECTACLE’

Public spectacle lynchings were used to incite terror, ricocheting through Black communities across the South. “Even one lynching reverberated, traveling with sinister force, down city streets and through rural farms, across roads and rivers,” Wood wrote in her book.”

“As Jean Toomer described it, one mob’s yell could sound ‘like a hundred mobs yelling,’ and the specter of the violence continued to smolder long after it was over.’”

Novelist Richard Wright once wrote that lynching shaped the Black experience in such a profound way that it conditioned the existence of Black Americans to the threat of “some natural force whose hostile behavior could not be predicted.” Wright, author of the classic novel “Native Son,” wrote, “I had never in my life been abused by whites, but I had already become as conditioned to their existence as though I had been the victim of a thousand lynchings.”

Lynching was shocking and barbaric. Lynching photographs captured the brazen cruelty of white mobs who were so audacious they did not fear arrest and were willing to be photographed with the victims.

Lynchings were “often deliberately performative and ritualized, as if mobs expected their violence to be noticed,” Wood wrote. “They were then frequently made public—even spectacular—through displays of lynched bodies and souvenirs, as well as through representations of the violence that circulated long after the lynchings themselves were over: photographs and other visual imagery, ballads, and songs, news accounts and lurid narratives.”

WIDELY DISTRIBUTED THROUGH THE U.S. MAIL

Lynching photographs and postcards were shrewdly distributed — often for profit — across communities by hand and through the U.S. mail. They were often sold for as little as a quarter, which would be worth about $3.46 today.

It is unknown how many postcards were printed and circulated. But hundreds of these images were later collected by museums, book authors and archivists. Many images, according to historians, were placed in private homes, attics and basements, then passed from generation to generation. The racist terror lingered long after the bodies were cut down.

“People would send lynching photos to their family,” said Seth Kotch, an associate professor in the American Studies department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “It was something to be celebrated to be a part of the white majority, not something people were ashamed to celebrate. They thought they were doing something good. They were not embarrassed.”

Lynchings and coverage by white newspapers would “reinforce this narrative of Black people being dangerous and needing to be subdued,” according to Chinyere Osuji, a visiting associate professor in the University of Maryland’s Department of African American Studies. “And that this was how you’re supposed to treat Black people, kind of perpetuating white supremacy.”

THE LYNCHING OF ELL PERSONS

On May 22, 1917, in Memphis, Tennessee, vendors set up shop and sold food at the site of the lynching of Ell Persons, a 50-year-old Black woodcutter. More than 3,000 white people came to watch.

“The crowd atmosphere was almost kind of an excitement, kind of a happy carnival like atmosphere,” said Jessica Orians, media strategist at The Lynching Sites Project of Memphis.

Ell Persons was falsely accused of killing Antoinette Rappel, a 16-year-old white girl whose decapitated body was found at Wolf River Bridge in Memphis. Persons was arrested and sent to Tennessee State Prison in Nashville. As officers brought Persons back to Memphis for trial, a white mob captured Persons and lynched him at the Wolf River Bridge. His body was burned while a crowd of about 3,000 people watched. His body was then decapitated, and some of his other body parts, including hands and feet, were cut off. Members of the mob took his head to Beale Street in Memphis for crowds to witness, Orians said.

A May 22, 1917 headline from the News Scimitar, a prominent Memphis paper at the time, read, “THROW HEAD OF PERSONS INTO CROWD OF NEGROES.”

Persons’ head was photographed and printed on postcards, according to the Lynching Sites Project of Memphis.

The Chicago Defender published a photo of Ell Persons’ severed head on the front page of their Sept, 8. 1917, issue.

The headline read “NOT BELGIUM—AMERICA.”

“The head of Ell Person, who was burned to death in Memphis, Tenn.,” said the accompanying story in The Defender. “This head was cut off the body, and is seen here with both ears severed, his nose and upper lip cut off.”

“Racial terror lynching is a demonstrative kill,” Fakunle said in an interview. “Much of the motivation of killing was to send a message to Black people. ‘If you go out of line, this is what could happen to us.’ That is why the bodies of victims were often left there. To make a statement.”

“It was seen by spectators as their form of justice. To maintain their whiteness,” said Fakunle. “White people weren’t brought to justice. That is what sets lynchings apart from what sets other killings of murders apart. It is a special form of savagery and barbarism.”

LYNCHING PHOTOS WERE STAGED LIKE HUNTING TROPHY PHOTOS

Hunting photographs were popular around the turn of the century. Wood said that lynching photographs were used in the same way that hunting trophy photos were used. The styles were similar: Men posed around the prey the same way white mobs posed around the body of a Black person who was lynched.

Lynching postcards weren’t often produced after the 1930s, according to Wood. Communities were careful about who received lynching postcards or photographs. By the 1930s and 1940s, white people were often embarrassed and didn’t want these photos circulating outside their towns, Wood said.

However, there is evidence people were sending postcards to families in other states despite laws prohibiting people from sending any violent or incendiary material through the U.S. mail, according to Wood. If postcards were sent in the mail, they would have been sent in an envelope.

NEWSPAPERS ADVERTISED LYNCHINGS, WHICH DREW PROFESSIONAL PHOTOGRAPHERS

Newspapers contributed to the terror, Fakunle said, by printing the time and date of lynchings. Newspapers also contributed to the violence surrounding mobs and lynchings and instilled further fear in the Black communities.

When lynchings were announced or advertised, they were portrayed as a family gathering, as a celebration, Fakunle said in an interview. “Bring your kids to watch someone get ceremoniously killed. The indoctrination of children started early,” Fakunle said. “The ideology of white supremacy was passed on to their children as soon as possible. In their mind, that is what their children needed to see.”

Newspapers “will have to answer why [lynchings] were perpetuated for so long,” Fakunle said. “Communities have suffered, and we need to repair the community … to give them the resources that were systematically taken away.”

Wood said that most lynching photographs were captured by members of the mob or “amateur photographers who came to the scene with their Kodaks.” But in some lynchings, professional photographers came to capture the gruesome public spectacles. They often would vie for the perfect vantage point to get their shots, Wood said.

“One photographer,” capturing the lynching of Henry Smith in 1893 in Paris, Texas, Wood wrote, “climbed ‘high in a tree … so as to command an elevated view of the scaffold, and thus obtain the best possible views of the torture and final cremation.”

Twenty-three years later, in Waco, Texas, a photographer named F.A. Gildersleeve made requests of local officials to get prime access to the torture and lynching of Jesse Washington. Having received early notice that the lynching would happen on the lawn of City Hall, Gildersleeve received permission from the mayor to take photographs from windows in City Hall, according to Wood.

Gildersleeve took photographs up close, capturing the charred body of Washington. Professional photographers, Wood argued, “may not have participated in the violence directly, but neither were they recording events as outside journalists or commentators. They produced these photographs to profit, printing them in celebratory souvenir booklets of the lynchings or making them into postcards to be sent to sympathetic eyes.”

BLACK PRESS, NAACP COVERED LYNCHINGS TO FUEL ANTI-LYNCHING CAMPAIGNS

The photographs of lynching victims were more likely to be printed on the front pages of Black-owned newspapers.

It was more difficult for the Black press to receive photographs of lynchings, Wood said in an interview. Someone sympathetic to their cause would have to send photos to them, and it could be weeks after the actual lynching that they received a photograph. It is unclear who sent the photos to the Black press, but Wood suggests white allies may have served as investigators for the NAACP.

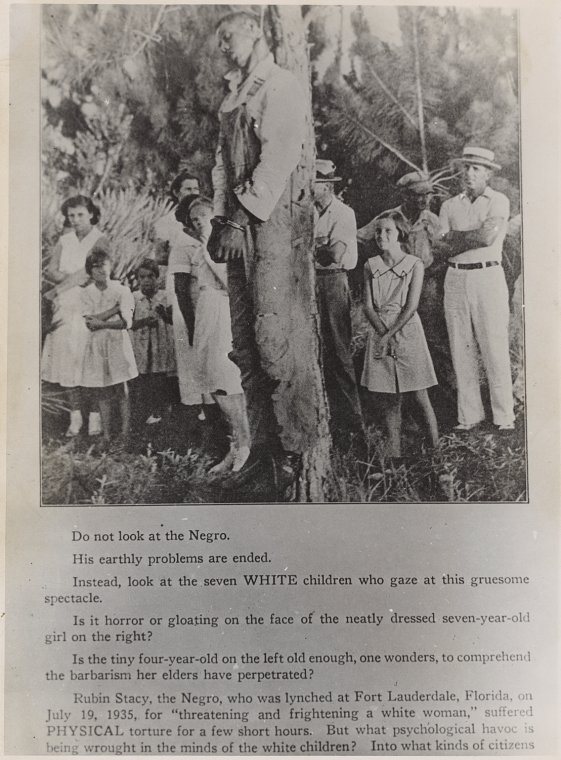

On July 19, 1935, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Rubin Stacy, also known as Reuben, was lynched after he was falsely accused of “threatening and frightening a white woman.” The postcard that captures the conventional lynching shows white people surrounding his corpse, with white children gazing up to it. His hands are bound, in the forefront of the image, as the children and other white people surround him, staring up at his body.

The photo was published in an NAACP journal in 1937, and then used in an anti-lynching campaign that condemned the white people staring at Stacy’s body.

The NAACP printed 100,000 copies of the pamphlet for 25 cents a hundred to give to NAACP branches, churches, women’s groups, and other organizations. The pamphlet encouraged attention to the white children around Stacy, rather than his body.

“Do not look at the Negro. His earthly problems are ended,” the pamphlet said. “Instead, look at the seven WHITE children who gaze at this gruesome spectacle. Is it the horror or gloating on the face of the neatly dressed seven-year-old girl on the right? Is the tiny four-year-old on the left old enough, one wonders, to comprehend the barbarism her elders have perpetrated?”

In the photo of Stacy, a little girl is holding her hand in the way [that] a child is perplexed and uncomfortable, said James Allen, author of “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.” “She is being photographed and looked upon, but is hiding because she cannot process what is going on,” Allen said. “No child that age is a monster.”

THE CONVENTIONS OF LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPHS

When Allen, author of “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America,” started his career in antiques, he had little idea of what a lynching photograph or postcard was. Allen said he believes that perhaps 500 to 700 postcards are left in existence. These postcards were most likely kept either in private collections, museums, or are still in families’ homes, Allen said.

The rest have been lost to history, whether discarded or destroyed. “They have all the evidence of a crime, [but] no one saw it as a crime,” Allen said.

The majority of lynching photos have people in them, according to Allen. People would often surround the body in the image, lined up like a congregation in a church. “It says something about the sacrificial aspect of a lynching,” he said.

“The greatest majority of spectators there for a lust for blood,” Allen said. “They wanted to see a body sacrificed, burned, tortured. They wanted it to be a Black body.”

According to Allen, newspaper photographers often would hurry the mob to bring the victim to take the photograph in time to process the image before the crowd left the scene.

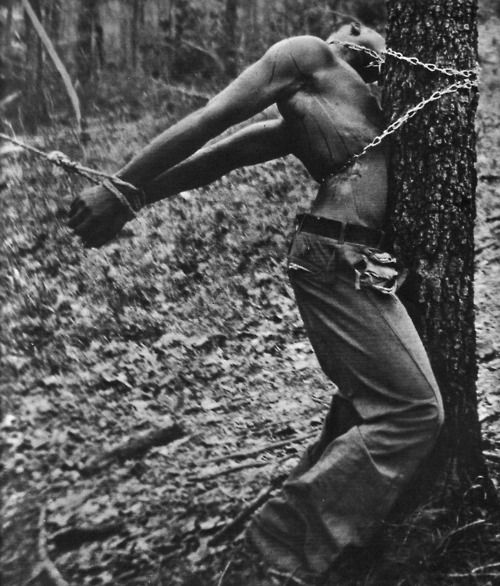

On July 13, 1937, Robert McDaniels and Roosevelt Townes, two Black men, were lynched in Duck Hill, Mississippi. According to Allen, the photographer was able to stop the lynching and move the crowd out of his line of view to get multiple shots of the two Black men before they were lynched. The photos were then sold at The Campbell Portrait Studio in Grenada.

However, Allen found that the most abominable photographs were the ones of the victim alone in empty spaces. They appeared trapped, in a world without a protector, and stripped of their rights.

Photographs were often captured by local professionals, according to historians, and framed and lit by extemporaneous props such as the headlights of a car. Small towns often had a designated photographer for weddings, funerals, parties — and lynchings.

Printing images on postcards was the most inexpensive way to print photographs, according to experts. Professional photographers would immediately print the image for the community, while some tourists and local residents would bring their own cameras, according to Allen.

People waiting for lynchings would bring baskets of food, Allen explained. The mob may have been collecting the victim, and observers wouldn’t want to miss out. They fed themselves and their children as they were waiting.

WHITE PEOPLE MONETIZED THE MURDER OF BLACK PEOPLE

The visceral impact of lynching photographs devastated Black communities across the country, often triggering trauma caused by racism and oppression.

Lynchings “went beyond simply just hanging a person. Black men’s genitalia region being targeted has so much to do with … the anxieties — social anxieties — around interracial couples and interracial sexual interactivity,” said Shane Bolles Walsh, a lecturer in the University of Maryland’s Department of African American Studies. “People were lynched most commonly for economic anxieties … (the) desire to control labor.”

Walsh added that many postcards of lynchings were posed and framed to improve the composition of the scene.

“I read anecdotes of people moving their vehicles so that the headlights and the cars could light (the body) up further,” Walsh said. “So you could backlight the pictures more, so the photo would take better using the camera technologies. You know, this is one of the things that is just so hard to wrap our heads around.”

The “commemorative” lynching photographs, Walsh said, were not simply taken as teaching tools, but were also copyrighted and printed for profit.

“They collected these photos — not to enjoy, to appreciate — but to capture the historical impact of these atrocities. And in terms of legacy, it affected … American people to a much greater depth,” Walsh said. “People monetizing murder of African American people is, I think, another really important thing, because for a lot of people it was a money-making venture, as grotesque as that is to even say out loud.”

Walsh said that the act of white parents taking their children to lynchings played a direct role in developing generations of overt, aggressive, racial violent hostility, ultimately normalizing the violence and terror inflicted on Black Americans.

“These are social ideologies reinforced in an intergenerational context,” Walsh said. “You see all the children in so many of these lynching postcard photographs.”

While white families felt empowered, justified and protected from reprisal, Black community members responded viscerally. These postcards are symbols of the white supremacist social ideology being reinforced throughout this period, Walsh said.

“I think it’s a way not just to reinforce, but a way to socialize people to find this type of behavior acceptable,” Walsh said.

“It’s the psychological damage that would then impose on a person, it’s kind of hard to conceptualize, particularly people who had dads, brothers, sons … because of how easy it could be,” said Walsh. “Those individuals had families, so it’s a way that people could quite literally identify with what they were seeing … the phenomenon of these postcards.”