By Paulina Duque

Note to readers: This story contains graphic and disturbing images.

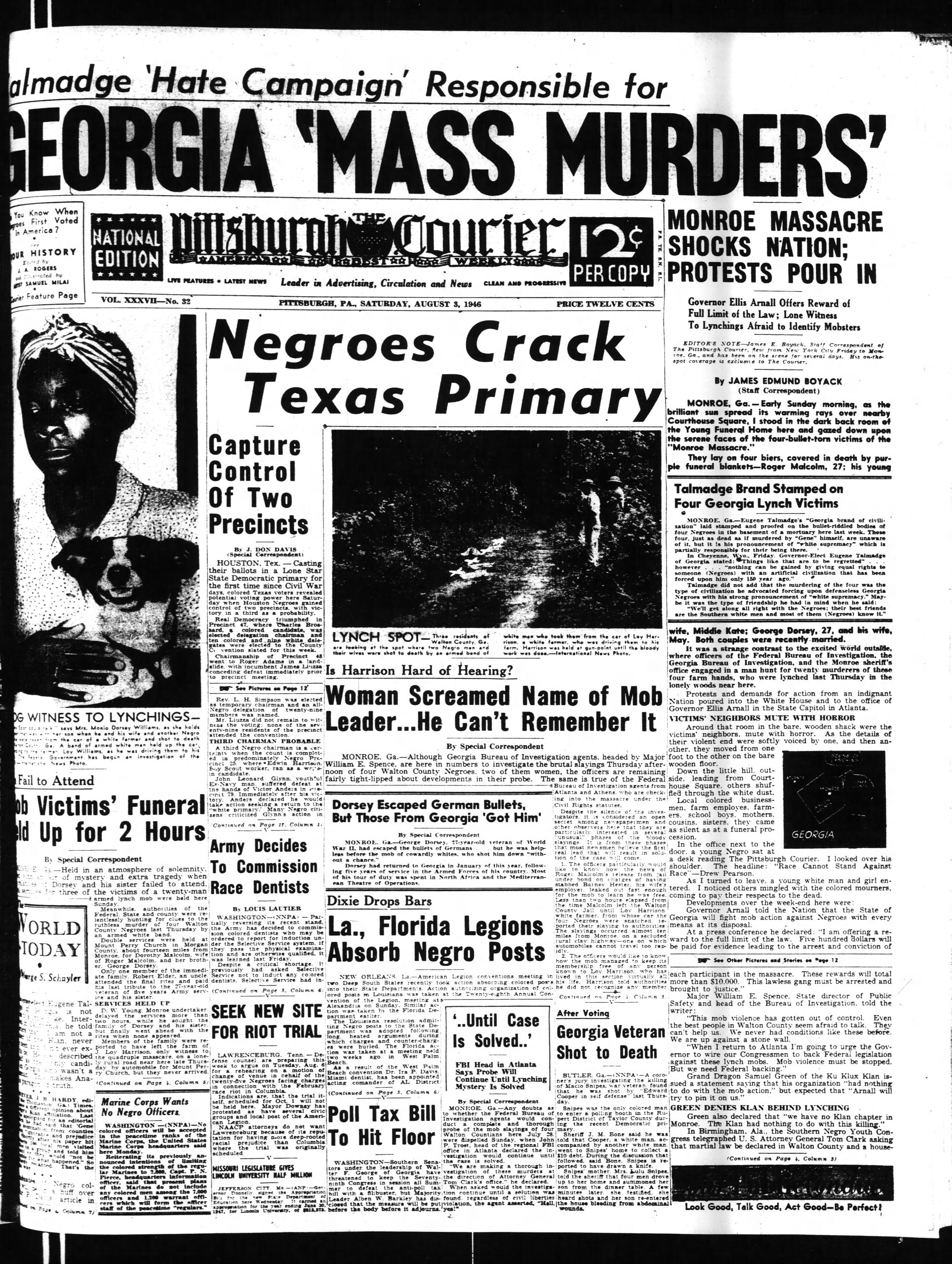

On the night of July 25, 1946, outside of Monroe, Georgia, a mob of white men linked to the Ku Klux Klan murdered Black sharecroppers George Dorsey, Mae Murray Dorsey, Roger Malcom and Dorothy Dorsey Malcom at the Moore’s Ford Bridge near the Walton County line.

Historians call it the last documented mass lynching in America.

Two weeks before that night, Roger Malcom was arrested for allegedly stabbing his white employer, according to the Associated Press. White landowner Loy Harrison agreed to drive Dorothy Malcom, Roger’s wife, along with fellow sharecroppers George and Mae Dorsey, to post Roger’s bail.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

On their way back, the car was stopped by a mob of white men who pulled the sharecroppers out of the car, beat them, and shot them by the Moore’s Ford Bridge, according to The Pittsburgh Courier.

The Pittsburgh Courier, the country’s most widely circulated Black newspaper at that time, sent Black correspondent James E. Boyack from New York to Monroe to cover the FBI investigation of the lynchings.

“I guess, what I would say is we can’t underestimate the kind of risk that Black reporters and photographers held when they went into these areas to do this work because it was not welcome,” said Laura Wexler, author of “Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America,” in an interview with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

“The role of the Black newspaper in reporting on lynching was to publicize the horror, and galvanize the public to act and to demand justice.”

After the Moore’s Ford lynchings, the town’s only Black undertaker sent word about the murders to his brother-in-law at the Atlanta NAACP, Wexler said. The Atlanta NAACP then informed Walter White, the executive secretary for the NAACP, bringing the lynchings into a new national light, according to an NAACP antilynching legislation article.

After an FBI investigation concluded, no arrests were made in the case. In 2021, a federal appeals court ordered that the case be reopened, but the government ultimately appealed the requests, keeping the sealed records a secret, according to The Washington Post.

THE BLACK PRESS TAKES A STAND

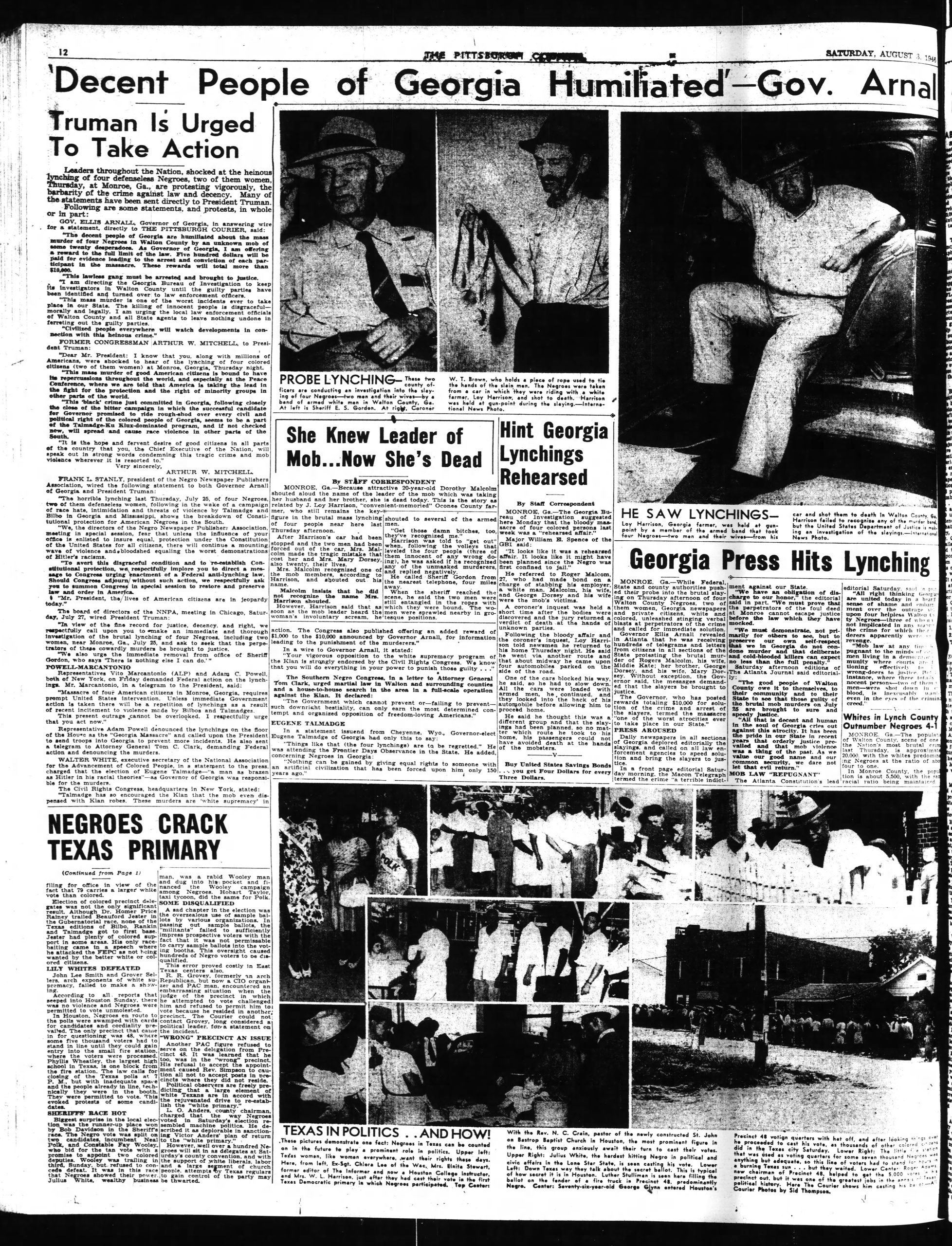

Wexler said that Black-owned newspapers were often the first to send photojournalists and correspondents to investigative lynchings. No photographs of the Moore’s Ford victims at the scene of the crime are available to the public. The only photographs publicly available of the last mass lynching are those that capture the aftermath, according to experts.

The Pittsburgh Courier published photographs of the victims’ funerals, humanizing the murdered sharecroppers by capturing the grief and pain of their family members. The Courier also published images of a coroner holding the rope that had been used to tie up the sharecroppers. The Courier published close-ups of the noose, which was still hanging at the lynching site.

Wexler said The Courier, publishing for a Black audience, weighed the risk of objectifying the victims and sensationalism “against the possible impact that these photographs would make.”

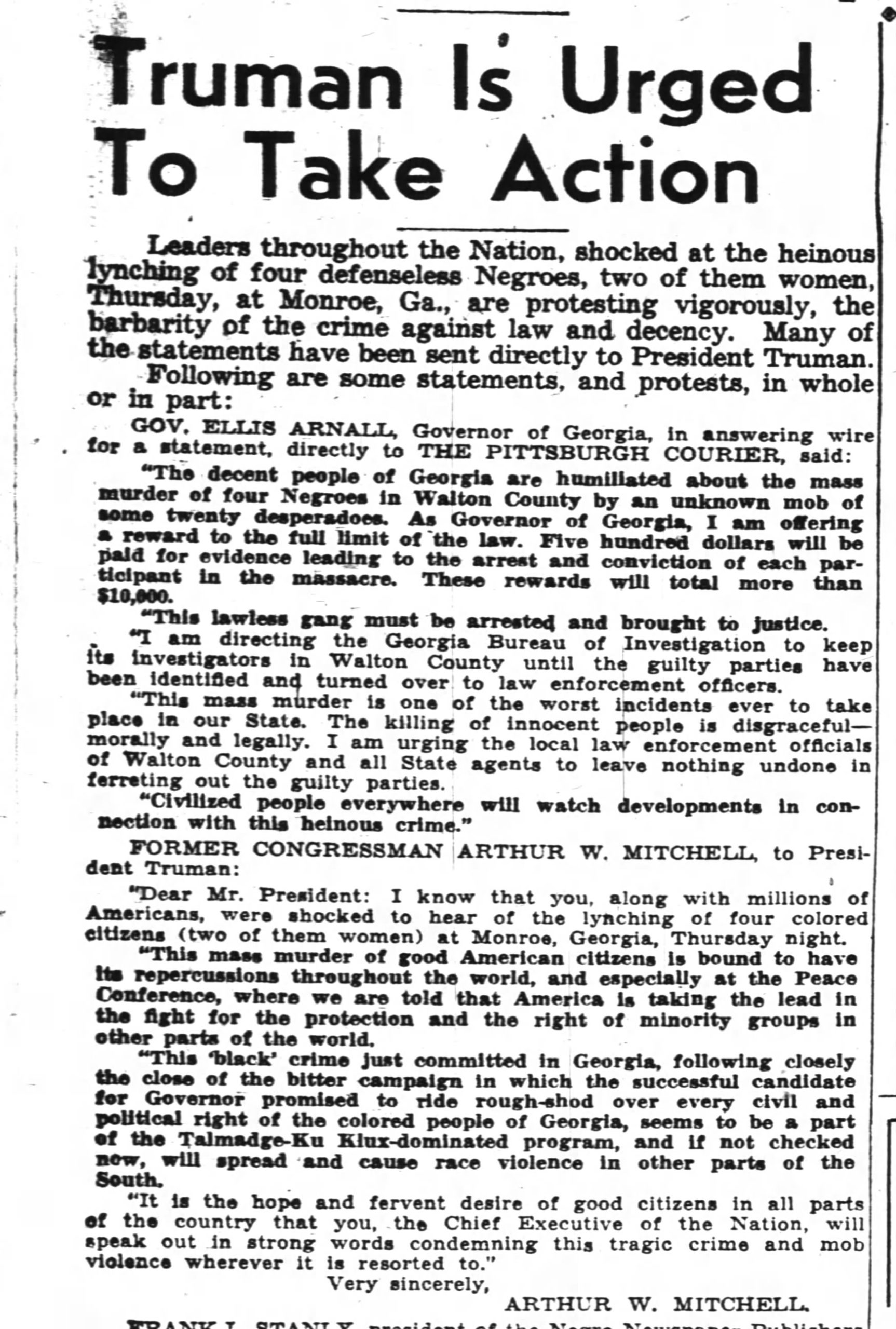

The Pittsburgh Courier and other Black newspapers demanded action and published statements from officials asking the public for any information that would lead to an arrest, but in the end, no one was arrested for the crime.

“Black-owned newspapers played one type of role, and the white-owned, local and regional newspapers played a different role. The national white papers played a different role,” Wexler said. “The role of the Black newspaper in reporting on lynching was to publicize the horror, galvanize the public, their readers, to act and to demand justice.”

The Black press took the responsibility of investigating the crime and documenting the investigation, Wexler said. Meanwhile, the white press released statements demanding an arrest, based on the published articles from The Pittsburgh Courier, which followed the lynching investigation and actively demanded change.

White-owned papers’ “mission was to conserve the good name of Monroe, in particular in Walton County,” Wexler said. “And their stance was ‘This was the work of a few bad eggs.’”

Wexler said there was a divide between the conservative papers and some more progressive white-owned papers, where “some of their photographs were intended to show how backward Walton County was.”

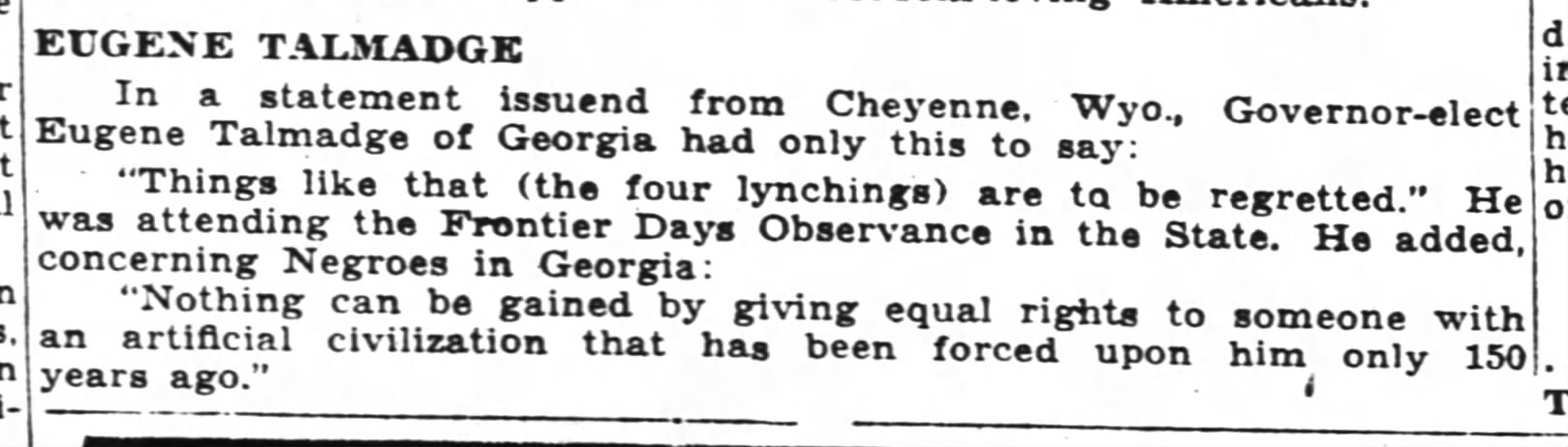

The Pittsburgh Courier published responses to the lynchings made by white papers, white churches, and white elected officials — including Georgia governor-elect Eugene Talmadge. Talmadge called for the mob that committed the lynchings to be found responsible, but he refused to acknowledge any of the deeply rooted racism and inequality of Black people that perpetuated violent behavior.

75 YEARS LATER

Some photographs from the early 1900s show lynched victims or angry mobs and brutalized bodies, but by 1946, lynchings were no longer public spectacles.

“What people learn is that it was no longer possible to have a lynching like this and be 100% sure you could get away with it, where they keep it under wraps,” Wexler said. “Like it was, you couldn’t control the aftermath of the lynching, even if you could control the lynching itself.”

“A man was lynched yesterday” read a flag hung by the NAACP outside its New York City headquarters. The NAACP displayed the flag from 1920 to 1938 as Black people were murdered in mass lynchings across the country, according to a PBS article.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, lynching is defined as a group of people killing a person for an alleged crime, outside the court of law and without trial. It’s been 75 years since that night by the Moore’s Ford Bridge in 1946. The Moore’s Ford lynching is still known as the last mass lynching.

Wexler compared the photographs used by the Black press when reporting and investigating the Moore’s Ford lynchings to footage of police brutality posted on social media.

The videos are not taken to celebrate or watch later on, but to document the ongoing violence against Black people in America, deeply rooted in a racist past that has consequences today.

“These photographs,” Wexler said, “are the equivalent of today’s cellphone videos.”