By Vanessa G. Sánchez

Note to readers: This story contains graphic and disturbing images.

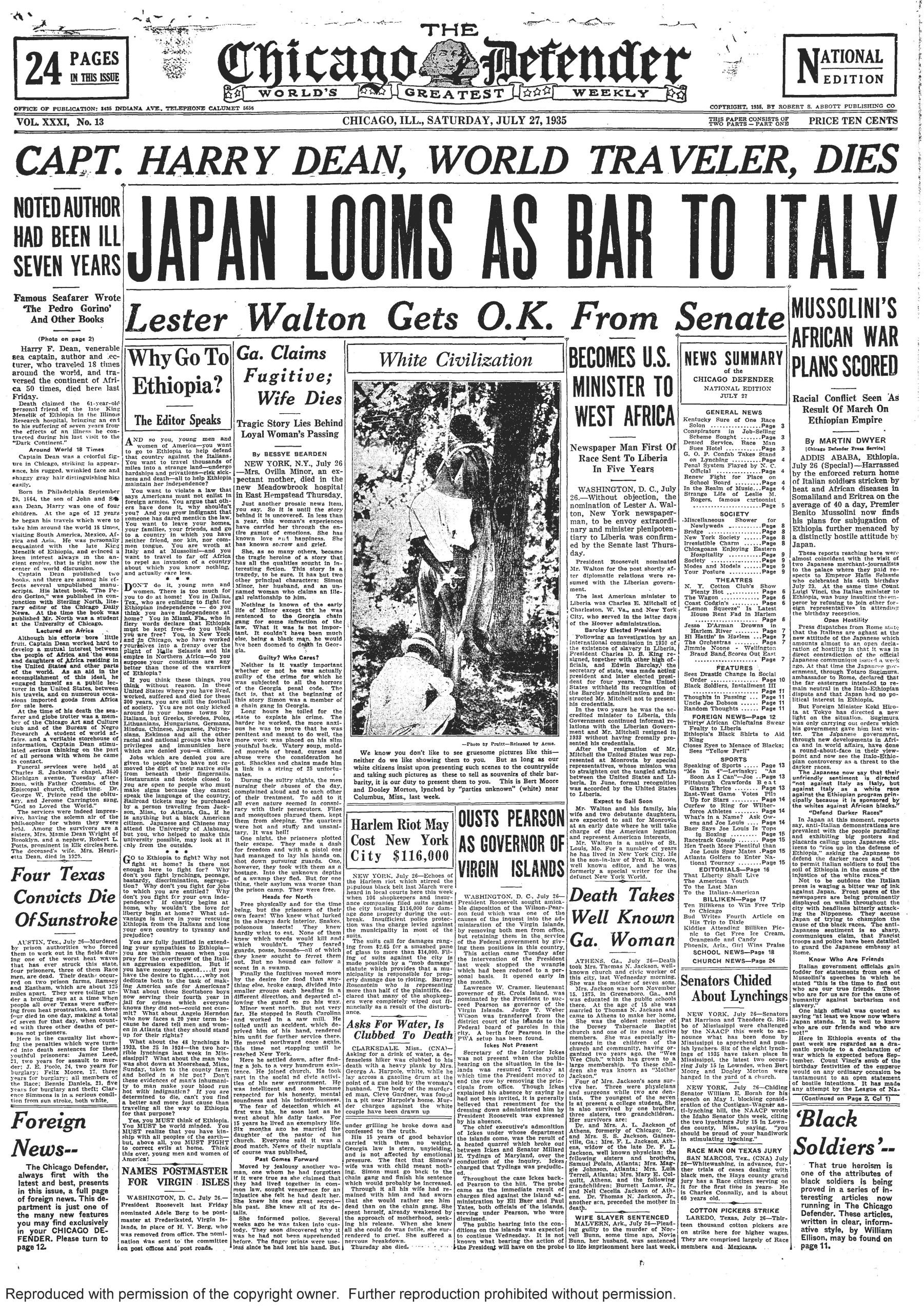

On July 27, 1935, The Chicago Defender, the nation’s most influential Black weekly newspaper, published a front-page photograph of Bert Moore and Dooley Morton’s bodies hanging from an oak tree near Columbus, Mississippi.

“We know you don’t like to see gruesome pictures like this—neither do we like showing them to you,” The Defender wrote in the caption published beneath the photo. “But as long as our white citizens insist upon presenting such scenes to the countryside and taking such pictures as these to sell as souvenirs of their barbarity, it is our duty to present them to you. This is Bert Moore and Dooley Morton, lynched by ‘parties unknown’ (white) near Columbus, Miss., last week.”

Collected and circulated by the Black press and the civil rights movement organizations, photographs of victims of racist terror lynchings exposed America to the injustice of racist terror lynchings of Black Americans.

A week earlier, The Defender reported that a white mob had taken the two men from police custody at Clarksdale, Mississippi, and transported them to a nearby location to be lynched. “They chased the men, Bert Moore and Dooley Morton, 26-year-old farmers, caught them, beat them, tied them standing on top of a car, to trees, drove the car from under them and left them dangling in a churchyard where all might see,” wrote Defender staff writer J.W. Harrington.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

On July 15, not long after the two Black men were lynched, the phone rang for Otis N. Pruitt, a white commercial and studio photographer based in Columbus, Mississippi. “Come quickly, he was told, there had been a lynching, a double lynching,” media history professor, Berkley Hudson wrote in “O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: The ‘Modest Aspiration and Small Renown’ of a Mississippi Photographer, 1915–1960.”

Hudson grew up in Columbus, Mississippi, and was photographed by Pruitt when he was a kid.

“Although the images didn’t appear in the local press, Pruitt was nonetheless contacted to document the lynching,” wrote Hudson. “Hundreds of spectators came to look at the bodies of the lynched men before they were cut down, more than twelve hours after the lynching occurred, one local newspaper wrote the next day.” Hudson said that the Pruitt photo may have become a postcard at some point but he has not been able to find any evidence.

The lynching photograph was sent to The Chicago Defender, which offered a fundamentally different account of the attack. A white woman said that the two men attempted to attack her but, contrary to what The New York Times and the Associated Press reported, The Defender wrote that no substantiated evidence of the attack had been provided.

“But no one was needed. After all, in this Godforsaken hole of the world, a white woman does not have to prove that she was attacked—she merely has to say it.”

Berkley Hudson said that it took him several years to figure out the story behind the photograph. Residents in the town, including his mother, who was in her 20s when the two Black men were lynched in her hometown, didn’t talk about it until Hudson started to investigate.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

“I would walk down the streets when I would go back home and there were people who were carrying these stories in their heads and their hearts,” he said. “They knew the stories. They would only speak about them within the protective sanctions of their own families, friends.”

However, a series of photos that appeared in the Black press 10 years later laid bare to white audiences what Black Americans had long known, seen and experienced.

In August 1955, after white men kidnapped, tortured and shot 14-year-old Emmett Till, wrapping him in barbed wire attached to a 75-pound metal fan and throwing his body into the Tallahatchie River, his mother called The Chicago Defender and Jet and Ebony magazines to photograph his body.

“Let the world see what I’ve seen,” his mother, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley, told reporters.

Fifty thousand people attended her son’s funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Chicago, and a series of photographs ran in the Black press that some think ignited the modern civil rights movement It was an act that changed the world, according to Ebony magazine.

“I couldn’t bear the thought of people being horrified by the sight of my son”, Till-Mobley said when she explained why she asked for an open casket at her son’s funeral on Sept. 3, 1955 .

“But on the other hand, I felt the alternative was even worse. After all, we had averted our eyes for far too long, turning away from the ugly reality facing us as a nation.”

It was Till-Mobley’s courage to allow photographs of her son to be published and to open his casket at his funeral that became a catalyst for change, according to historians.

In 1966, three decades after Pruitt took the photograph of Bert Moore and Dooley Morton’s bodies, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a group of young activists who organized direct-action campaigns against segregation and other forms of racism, including voting registration of Black people in the ’60s, reclaimed the photo and published it again as an anti-lynching poster to inspire people registered to vote.

“It becomes a counter hegemonic,” Hudson said. “A visual artifact that moves through time and space and is used in different ways depending on who wants to claim it.”

Documenting violence and brutality became a piece of incalculable value to the movement, according to historians and civil rights activists. “Public awareness was crucial to our strategy,” said Mary E. King, a member of SNCC’s Communications Department. “Without national exposure and mobilized public opinion, there was no point to the struggle. The sacrifice would be lost in oblivion,” she said.

SNCC’s use of the photo gained so much attention that the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a secret police agency created to spy on the civil rights movement, began investigating how the lynching photograph ended up in the hands of SNCC, Hudson said.

The commission, which used journalists to be their eyes and ears on the ground throughout the state, wrote a letter to the Commercial Dispatch, a white-owned newspaper, asking for information about the lynching photograph, according to Hudson. “They were really upset because civil rights leaders were using it to try to besmirch the image of Mississippi in the ’60s,” he said.

After Emmett Till’s lynching, authorities tried to bury him as quickly as possible. Till-Mobley asked them to send her son’s body to Chicago, and Jet photographer David Jackson came in to photograph Emmett Till’s body, which was mutilated beyond recognition.

“When she arrived at the train station to pick up her only son’s remains, the woman was outraged to see his ear severed, his teeth missing and his eye hanging out of the socket,” Ebony wrote.

No mainstream news outlets published the images of Till’s body, according to an account decades later in The New York Times, but the appearance of the photo in several Black publications made Till’s murder “the first great media event of the civil rights movement,” historian David Halberstam wrote in his book “The Fifties.”

“[It] was a turning point where generations got to do something,” said Charles Neblett, 80, one of the SNCC Freedom Singers founders and field secretary from 1961 to 1966 in Mississippi, . The Freedom Singers were a group who sang to raise funds for the organization and spread through music the Black struggle in the South to people all over the country. “We were not entertainers, we were organizers,” Neblett said.

Emmett Till’s murder forever changed Neblett, who was his same age when Till was lynched.

“That’s what got me,” Neblett said in an interview. “That’s one of the things I realized—I had no rights that any white person was duly bound to respect.”

Neblett joined the SNCC in 1961 and was arrested 27 times for trying to register Black Americans to vote, he said. Charged for “criminal anarchy,” the civil rights activist spent 30 days in Parchman Farm—the Mississippi State Penitentiary—a place he described as the “worst prison.”

“They put us in jail and say that we were trying to overthrow the state government of Mississippi,” he said.

Lynching photographs weren’t often published in white-owned newspapers. SNCC couldn’t trust the press, Neblett said. “We had to get it out first and tell the story,” he said. “They had the machinery to hide [lynchings and racial violence] from the public.”

When Jet and Ebony magazines published the photos and story of Till’s extrajudicial killing, it struck his entire generation. “It hurt everybody, and people had to figure out what they were going to do,” Neblett said.

In a 2016 interview for Time magazine, David Jackson said that the image he took more than five decades ago still has its power today. “I think it still expresses the pain and anguish of a huge part of our population that is still hoping for basic recognition of their humanity,” he said.

“With bright enough lights and an army of cameras trained in the right direction,” said Leigh Raiford, associate professor of African American Studies at the University of California at Berkeley. “Images were central to changing public opinion about the violent entrenchment of white supremacy in the South and that system’s overdetermination of Black life and possibility.”