By Gabrielle Lewis, Victoria Ifatusin & Jamille Whitlow

It was May 18, 1918, and Mary Turner was grieving. Her husband, Hayes Turner, had been lynched without a trial, accused of being an accomplice in the murder of a white farmer. Her unborn baby would be raised without a father. Infuriated by the injustice, she threatened to ask the courts to punish his killers.

The next day, Mary Turner was dead. Her naked, burned body, pierced by hundreds of bullets, hung from a tree by Folsom’s Bridge, 16 miles north of Valdosta, Georgia. Her abdomen had been cut open. Her baby, a month shy of being born, lay on the ground dead, its head crushed by a member of a white lynch mob who stomped on its skull.

When the Valdosta Daily Times, a white-owned newspaper, described the reason for her death, it said “her talk enraged” local citizens.

“The people in their indignant mood took exceptions to her remarks as well as her attitude,” the newspaper said, “and took her to the river where she was hanged.”

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

What that newspaper — and other white-owned newspapers — omitted were the gruesome details of her lynching. They failed to mention she was eight months pregnant, and her unborn baby was killed.

After Turner’s murder, the Daily Times reported, “Posses are to-night looking for other negroes … and feeling among both whites and blacks seems to be growing more intense.”

Turner was one of at least 11 victims in Georgia’s Lowndes and Brooks counties during what became known as the Lynching Rampage of 1918.

White-owned newspapers reported stories of these lynchings without including important details of the victims. These newspapers also justified racial terror through the language they used and the atmosphere they created.

“The newspaper owners and editors were white and they were biased in their coverage of lynchings,” said Jamie Landau, a professor of communication arts at Valdosta State University who analyzed newspaper coverage that preceded Turner’s lynching.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

Her death resonated locally and nationally, becoming the face of the NAACP’s unsuccessful drive for anti-lynching legislation, which began in 1922 and was blocked by southern Democrats. In 2007, the memory of her death inspired a grassroots initiative in Lowndes County: the Mary Turner Project, which is dedicated to education and racial justice.

Despite these efforts, some of Valdosta’s residents have pushed back against acknowledging the rampage and Turner’s death, said Mark Patrick George, the founder and coordinator of the Mary Turner Project.

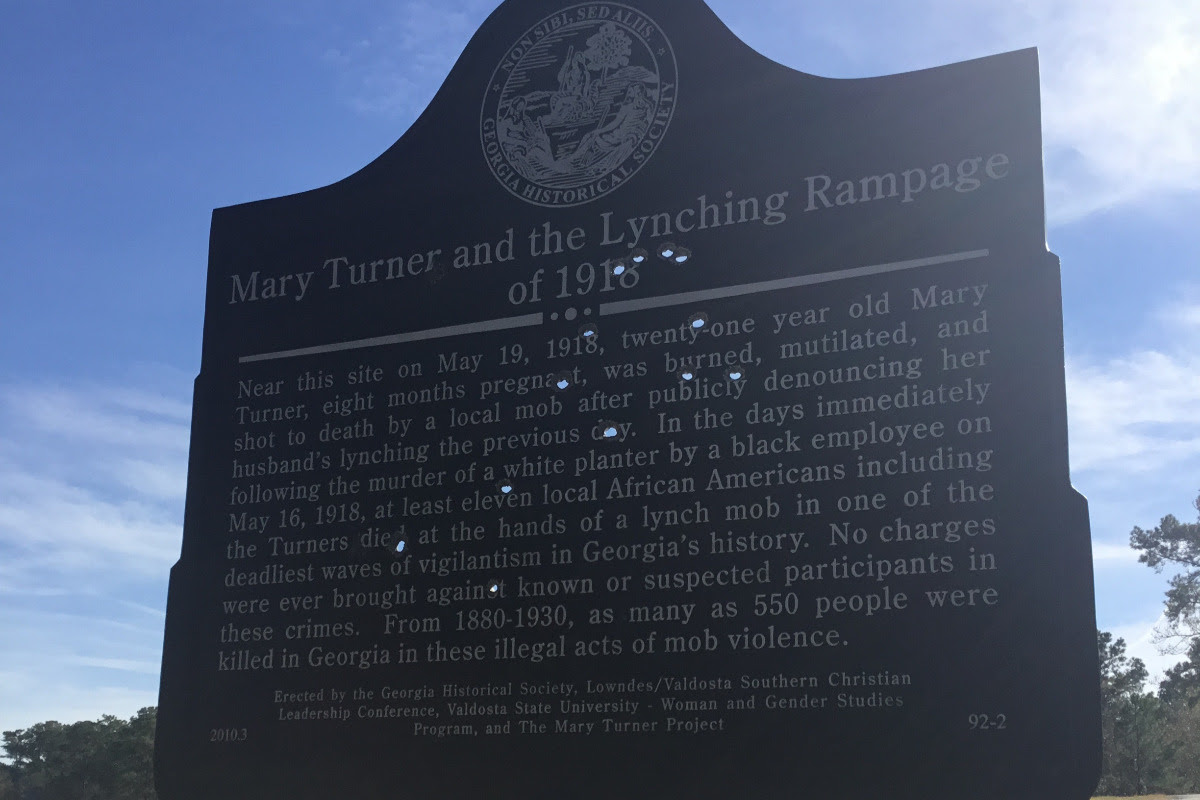

The original historical marker remembering Turner and the Lynching Rampage, which was erected in 2010, was shot through several times, George said. It’s been replaced by a tall steel cross with “Mary Turner 1918” etched onto it.

Differences in coverage

The Lynching Rampage was sparked by the murder of Hampton Smith, a white farmer, by Sidney Johnson, one of his Black workers. For more than a week, white people hunted for Johnson across Lowndes and Brooks counties, lynching several Black people along the way. The rampage ended when police shot Johnson dead and a mob hanged his body.

Coverage of the rampage differed depending on whether the newspaper was white-owned or Black-owned.

The Daily Times Enterprise, a white-owned newspaper in Thomasville, Georgia, covered Johnson’s death on May 23, 1918.

One of the front-page subheadlines announced, “Officers Wounded in Fight With Principal in Recent Murder in Lowndes County.” The newspaper detailed the shootout between Johnson and the police. The officers triumphed over Johnson, the paper said, by shooting a “volley of bullets” into him.

“A crowd immediately seized the body and tied it to the rear of an automobile,” the newspaper reported, “and the machine dashed out of the city, bound, it is believed for Barney, [Georgia], the scene of the crime where it was stated by the crowd that the body would be cremated.”

White-owned newspapers wrote conflicting accounts during the rampage, said Phillip Williams, the founder and director of the Wiregrass Region Digital History Project, a volunteer-based effort to document history in South Georgia, North Florida and Southeast Alabama.

Some newspapers said Johnson was hiding in swamps, while others said he’d left the area. Some wrote the Turners sheltered Johnson while he was on the run while others wrote they were possibly involved in Smith’s murder.

“It’s so convoluted because of just white people trying to find some way to justify what happened,“ Williams said.

But what white-owned publications omitted, Black-owned publications emphasized. The Chicago Defender, a Black-owned newspaper, reported on the rampage on May 25, 1918, noting Smith’s history of abusing his workers. He’d also previously whipped Turner when she refused to work longer without pay.

Walter White, then an assistant secretary for the NAACP, investigated the rampage, publishing a report in the September 1918 issue of The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine.

White wrote that after Johnson was found dead from the shootout, the white crowd seized the body, “unsexed it with a sharp knife” and tied him to an automobile with a rope around his neck. The car dragged his body in open daylight to Barney, where he was tied to a tree and “burned to a crisp.”

White also wrote the mob who lynched Turner wanted to “teach her a lesson,” and “she writhed in agony and the mob howled in glee.” No part of her lynching, including her pregnancy and the killing of her child, was excluded.

Williams said white-owned newspapers ran with common narratives that dehumanized Black people and victimized white people.

“A lot of them were just straight up trying to justify the lynching and terror,” Williams said.

The language itself also might have contributed to the violence, Landau said, by influencing the general atmosphere or “affect” of the places they covered.

“They’re increasing our anxiety and our emotions,” Landau said, “those who were reading this at the time … to kind of maybe join the mob or feel one way about supporting the lynchers versus not.”

‘A profound local legacy’

Landau said Turner’s story likely affected people because her lynching was different from the “Black male brute” trope.

“Mary Turner possibly became a symbol that could resonate because of her gender, and because of her body — her pregnant body — in a way that Rosa Parks was able to resonate when other bodies had been on buses for years,” Landau said.

Turner continues to have a “profound legacy,” Williams said, “upon local history, racial history, but just Black history in the U.S. in general because of how absolutely horrific it was.”

The Mary Turner Project began when George, who taught at Valdosta State University, assigned his students to read about her lynching. Some students wanted to continue work outside of the classroom, and their meetings with George evolved into the project.

Now, as a grassroots organization, George said the Mary Turner Project is “contributing to some pushback on the current backlash” against racial-justice initiatives.

The project has created a public lynching database, sponsored the rampage’s original historical marker and created a historical newspaper archive on its website.

The original historical marker acknowledged Turner was burned and mutilated, and how the rampage was “one of the deadliest waves of vigilantism in Georgia’s history.”

But it was hit repeatedly with bullets and had to be removed.

“I think those bullet holes are a testament to the local context that we still live in,” George said.

Valdosta now

Valdosta is a city of about 56,000. More than half the population is Black, according to 2019 Census data. George said Valdosta looks like many small rural communities in the deep South, with a courthouse in the center of town. It has a large military base and Valdosta State University nearby.

But there used to be a Confederate memorial on the Lowndes County Courthouse lawn. George said the two main streets, among many others, were named after Confederate soldiers.

“As for white backlash, there is no need for backlash because white folks control things to a large degree and white supremacy is normative here,” George said.

Valdosta Mayor Scott James Matheson did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

Dean Poling, the Valdosta Daily Times’ executive editor, has been with the newspaper since 1989. During his term, the newspaper had not written about the rampage until the Mary Turner Project was established.

“When they began the project, we began the reporting because we hadn’t heard about it as an institution,” Poling said. The Valdosta Daily Times does not have any microfilm newspaper archives from 1915 to roughly 1919, Poling said, because there was a fire “a hundred and some years ago,” and he presumes those archives were lost then.

When the paper started covering the rampage, it sometimes received calls criticizing the coverage, Poling said. The callers asked why the newspaper wanted to dig up the past.

Jim Zachary, the newspaper’s editor, acknowledged, “It was a gruesome event, but it happened.”

“While we care about the sensibilities and sensitivities of our readers, that’s something that is really important to us,” Zachary continued. “We also understand the historical importance of what happened and believe that the community deserves the unvarnished truth of what happened.”

In October, the paper published an editorial calling for Lowndes County to place a statue of Turner on the county courthouse lawn. “Her story must be told and retold and never forgotten,” the editorial read.

When the expanded Legacy Museum, which traces the history of slavery, reopened in Montgomery, Alabama, this fall, the Valdosta Times published articles about it. And Zachary wrote a column titled, “Listen to history, listen to now.”

“We are shaped by our history and even though we may not want to admit it, it is undeniable that slavery, lynchings, oppressive Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, vile racism and bigotry have shaped our nation,” Zachary wrote. “Only through honest conversations about our past can we be truthful about who we are, and it is only through accepting that truth that we can make better determinations about who we will become.”

The Valdosta Daily Times has not issued an apology, Zachary said, because their archives do not include the papers that covered the rampage.

The Mary Turner Project has a Daily Times clipping from 1918 — the article on Turner’s lynching — which George said was obtained at Valdosta State University’s library.

‘Proud to be a descendant’

Randy McClain, 56, is a descendant of two of the rampage’s victims — Will Head and Turner, though he didn’t know of his relation to Turner until the late 1990s. Head is his great-uncle. Turner is his great-aunt.

McClain arranged the first family reunion with Turner’s side of the family in 2008.

“It made me feel great, and it made me have a total, complete understanding of self,” McClain said. “When I met them, I instantly connected to most of them. And then I looked at a lot of them and how much we look alike.”

McClain, who lives in Atlanta, was raised in Brooks County. As a child, McClain said his connection to Turner was a “taboo discussion, and no one ever talked about it.”

Both sides of his family have told him that Head and Turner were diligent, proud and persevering against a racist system.

“I’m proud to be a descendant on both sides of that lineage,” McClain said, “because they were very proud of the accomplishments from a work perspective, earnings perspective, and just trying to exceed above what they were really allowed to because of the racism back then.”